Written by Dr Dawn Lees PFHEA, Student Employability and Development Manager, Kate Foster SFHEA Employability and Careers Consultant (WP) and Alice Potter, SCP

When an outgoing student commented that she hadn’t felt entitled to use the Career Zone, we were obviously concerned. After all, the staff are all highly approachable and knowledgeable, and there are a number of ways for students to engage both through the curriculum and in voluntary ways – so what had gone wrong? Why had this particular student not felt able to engage, how many others were there like her, and what could we do about it?

We know that students from underrepresented and disadvantaged groups often face barriers in developing their employability. The current global pandemic may have created even bigger gaps for these students. In 2020, The Sutton Trust noted that “the majority of students have had a prolonged period of time outside of education this year, with the largest impacts felt by those from the poorest backgrounds”. This is likely to disproportionally impact students from under-represented groups. Research from the social mobility charity UpReach (July 9, 2019) highlighted the challenges students from less privileged backgrounds face; ‘(they) have more limited access to careers advice at school, are less likely to have completed professional work experience and lack useful social networks.’

The graduate who raised concerns with us stated that she felt ‘WP (widening participation) students are much less likely to be resilient and confident with job applications, career progression and seeking support.’ Given these factors and a tricky graduate recruitment market, we wanted to explore these issues further.

We were lucky enough to secure a small grant from the Centre for Social Mobility. We wanted to better understand;

- The challenges and barriers that students from underrepresented and disadvantaged groups face with the development of their employability as they progress a) into university from school, college, or time out of education and b) from university when they graduate.

- How the Career Zone can further develop support to enable students from underrepresented and disadvantaged groups to be better equipped to overcome these barriers and challenges – and to get them to engage with us.

Methodology

In this pilot study, we adopted liminality methodology to explore challenges to progression utilising research by Hawkins & Edwards (2015, 2017). Liminal moments are those during which transition occurs, transporting an individual from one state of being to another (Turner, 1969; Van Gennep 1960). People facing liminal transitions often encounter “symbolic” monsters; challenges which threaten the self and which can lead them to become lost and doubting (see Hanley 2016 for discussion of self-imposed barriers). Facing liminal monsters involves grappling with uncertainty; overcoming the monster signifies the liminal threshold is crossed and transformation has occurred. We explored liminality in online workshops using Lego® Serious Play®, to offer students the opportunity to explore challenges, barriers, creatively explore new ideas and identities, and reflect on their experiences of liminal passage. The workshop facilitators (‘hosts’) learnt with the students how to smooth this passage and make journeys less barriered.

We had hoped to recruit one hundred First and Final Year undergraduates from Exeter and Penryn campuses, but unfortunately given the pressure from Covid that people were under, this simply wasn’t possible. However, we recruited 30 students with representatives from every College, with a range of WP markers – BAME, care leavers/estranged, mature, disability and bursary recipients.

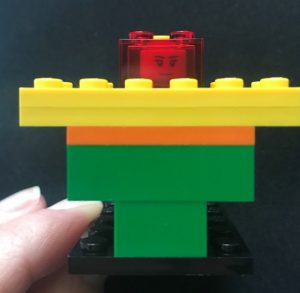

This was an entirely novel way for us to work, and captured the imagination of both staff and students. In workshop 1, the participants used the Lego® Serious Play® methodology to individually “build a model to represent the barriers and challenges you face in your employability’, and to ‘build a model that represents your dream career’.

“Build a model that represents your dream career.”

“The green and transparent red blocks represent a firm that is eco-responsible and innovative. The green plant on top is like a trophy on the roof representing a leading firm. The ladder represents my journey to the top in this company. The figure is outside the office to represent flexible home working. The yellow block extends to a blue block representing a river and a bridge, I want to work in a natural setting and have good work-life balance. The two flag pieces face in different directions to show that there are always multiple ways to look at things. “

Workshops

In the first workshop, the barriers that participants identified during the Lego® Serious Play® included being judged, prejudice, money, stress, self-belief, connections and not appreciating diversity. Being judged was an issue mentioned by many. This related both to competing with other graduates for positions, and to issues relating to diversity. Many felt that they could be judged unfavourably due to their background, either in the form of direct discrimination or prejudice or in the form of others not appreciating diversity and the value it could bring to a workplace. This was observed by BAME, disabled and mature students. The idea emerged of a theoretical “ideal” student. This student formed the basis of comparison that students measured themselves against, and the standard to which they feel judged against by potential employers. Falling short of these perceived expectations was felt most keenly by mature students who felt they didn’t fit the desired or expected profile for entry-level graduate roles.

The most widely mentioned support was the desire for a mentor. Participants wanted this mentor to come from the industry they were seeking to join. Most importantly this mentor should be someone ‘like them’ with similar lived experiences. Background (including socio-economic background), ethnicity and gender were important factors. Students wanted the opportunity to engage with individuals who had experienced the same challenges and barriers they were facing and had overcome them. Such individuals had perhaps not taken the ‘easy’ or ‘direct’ path. Participants felt it would be most useful to have access to a mentor who was in the early stages of their career, rather than a more senior professional.

It was thought that having a mentor could ‘make-up’ for not having access to the same connections within the professional sphere that others may have. Participants wanted their mentorships to be informal and more long term than our current Career Mentor Scheme of 6 months; they wanted consistent support throughout their career journey.

In workshop 2, they were encouraged to individually ‘build a model to represent what would support you with your career decision making and employability”. The next stage as a group was to build a collective model to represent that support to enable them to discuss in more depth, share their ideas and reach a consensus.

Many of the themes listed above were represented again. More of the participants spoke about the practicalities of the job application process. They spoke about having to complete online tests in order to proceed to interview for graduate schemes, the time taken to complete these and the knock to self-confidence when they were not successful. Some spoke of the frustration of not hearing back from employers. Others expressed dissatisfaction with the overall process. One participant described the interview process as ‘reductionist’, that employers were unable to see the value they offered as an applicant through this process. Both Brexit and COVID-19 were mentioned frequently as students had more experience of the impact these events on the job market, having been unsuccessful in applications.

“Build a model that represents the barriers and challenges you face in your employability.”

“The bricks form a wall, these are barriers to my employability. The red transparent brick represents communication difficulties, like seeing things through a lens”.

Some participants created models that represented multiple paths to their career goals, often categorising these paths as direct/indirect and easy/hard. For some, they viewed the easy or direct path as inaccessible to them, they viewed themselves as having additional barriers to overcome in order to reach their goal that some of their peers did not have. For others, the multiple paths represented confusion and a lack of knowledge relating to available options that ultimately could lead them to their goal, though perhaps by an ‘indirect’ route. A need for clearer information and guidance was expressed.

Next steps

We’re planning to build on this pilot project next year to include a longitudinal study of this cohort as they move into Year 2 or graduate. Recruiting a larger number of participants will enable us to ascertain if they raise similar issues.

We intend to review the content and impact of “Create Your Future” our mandatory employability programme for first years, to ensure it supports WP students in developing their employability skills and increasing their awareness of the opportunities available to them particularly in respect of leadership, resilience and team working.

Working with our Information and Marketing team (with input from WP students) we’re aiming to develop a communication and marketing strategy, to ensure effective communication to raise awareness of opportunities for students to develop their employability and career decision making. For example, we’re developing a focussed “landing” webpage on the Career Zone website to signpost WP students to relevant information and initiatives.

By reviewing and evaluating the pilot Access to Exeter bursary “peer mentoring support” project which was launched this year we hope to inform the introduction of future WP focussed schemes, for example for Disabled, Mature, BAME and care leavers/estranged students.

We are also going to explore the possibility of enhancing the Career Mentor Scheme for WP students to enable mentoring over a longer period.

Another tangible outcome of the Project is to review the data available for WP engagement (per marker) with work experience activities and opportunities for example. Access to Internships (A2I), internships and placements.

This has been a thought provoking project and should help us nuance our existing provision to better serve this group of students.

Huge thanks to the Project Advisory Board for supporting the development of this Project, and the Centre for Social Mobility for granting us research funding.