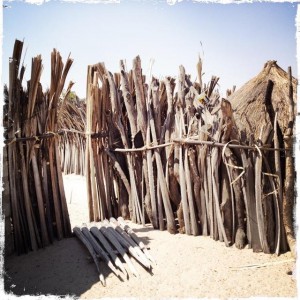

Gateway to the Homestead

By Helen John

Just over a year ago, I set off with my backpack to a village in the Ondonga region of Northern Namibia, not far from the Angolan border. My research centres on investigating the identities and belief systems of a village community in that area, to be researched through a programme of contextual Bible studies. In other words, I aimed to facilitate groups in the community to discuss their interpretations of a series of New Testament texts. This was with a view to understanding how the influences of both traditional culture and worldviews, and Christianity inform the community members’ understandings of the text and their wider identities and beliefs.

In preparation for my fieldwork, I had read extensively on the history, culture and religious beliefs in the area, both pre- and post-missionisation (which took place from 1870 and, in the area I was in, was largely undertaken by Finnish missionaries). However, it was important also to engage in my own ethnographic work to arrive at a fuller understanding of the way of life in the home and community in which I was staying. This occupied roughly the first half of my stay in the village of Iihongo. Following on from that, and in order to take into consideration both gender and seniority, I conducted contextual Bible studies with three groups: women, men, and children. I hoped to highlight oft-marginalised voices and unveil some unique cultural interpretive perspectives.

Palms around the Homestead

For each text studied, we discussed prominent themes and related those to life ‘on the ground’. We then discussed what was happening in each text and compared and contrasted that with the local context. In some cases, the participants saw striking parallels and similarities. At other points, they discerned divergence between the text and their own experience. Both outcomes were equally enriching for my own understanding and revealed something about the encounter between Christianity and the local context. What I had suspected prior to embarking on this fieldwork was that the perception of Christianity as encountering and replacing local worldviews was an oversimplification of the case. The reality on the ground was a much more subtle interplay between these systems.

A Hut in the Homestead

Take the Legion narrative by way of example: a figure possessed by a multitude of spirits occupies wilderness and graveyard sites, set apart from his community. This narrative resonated with the participants. It was suggested that we might understand Legion as having experienced a ‘nightwalking’ episode, whereby (as has been reported in the local context) someone awakes in a graveyard having gone to sleep at home. Others understood graveyards and wild spaces as places restless spirits and ancestors occupy, sometimes engaging with the local community members. The spirits might occupy Legion in the graveyard, thereby isolating him from help from members of his community and facilitating his demise. Still others felt that the spirits plaguing Legion might have been sent his way by a member of his community wishing misfortune on him. These interpretations suggest that pre-Christian understandings of a spirit-matrix and human-spirit interaction pervade current Christian interpretations. The comprehensive analysis of the transcripts that I will undertake in due course will enable me to present a more detailed picture of the various understandings of the texts studied.

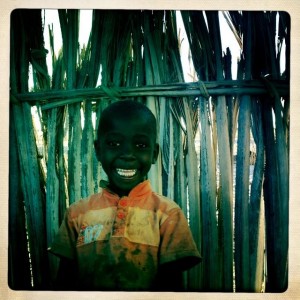

Child in the Homestead

Life in this community and the research as a whole was at once fascinating, challenging, rewarding, distressing, illuminating and puzzling. I was living in very different conditions than I was used to; I had shelter in the form of a fine breeze-block hut but it was without electricity or running water. I had a vehicle that seemed determined not to play ball. However, I had the great privilege of living within a family homestead and went to the village school to improve my language skills. I encountered amazing levels of hospitality and assistance with my research but was, at times, intensely isolated and aware of my own ‘otherness’.

I am extremely grateful for the opportunity I have had, not only to further my research skills and (of course) make gains towards the completion of my PhD, but also to learn about myself through this stay in Iihongo. When I first went to this region of Namibia 17 years ago as a volunteer teacher, I fell in love with the palm-dotted landscape, the hospitality and the relaxed pace. I appreciate those as much as ever now but I know my own limitations better, too. Communal life, limited resources and services, and the challenge of fitting in to an extended family structure in a different culture all presented significant challenges to my approach as a researcher with my own cultural conditioning. The contents of my ‘backpack’ were often out of place and positively unhelpful: closely guarded privacy, technological reliance, independence, high level of mobility, fast-paced working life and an individualistic outlook. However, my host community was generous in its encouragement, participation and, most of all, its forgiveness when I tripped up. So, it has been an all-round learning experience – but what a setting to in which to learn!