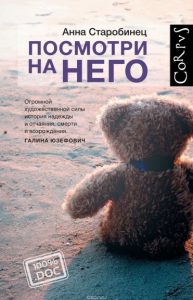

Book: Look At Him (Posmotri na nego, 2017) is the seventh book for adults by Russian novelist, children’s author, screenwriter and journalist Anna Starobinets. The English translation, by poet and translator Katherine Young, will can be pre-ordered from Slavica in the US with a September 2020 release date. (UK rights are still available). In Look At Him, Starobinets unflinchingly describes what happened after a routine scan in 2012 revealed that her unborn child had a fatal congenital condition, tracing her subsequent hunt for compassionate clinical care in Russia and in Germany, and the aftermath of her decision to terminate the pregnancy.

Book: Look At Him (Posmotri na nego, 2017) is the seventh book for adults by Russian novelist, children’s author, screenwriter and journalist Anna Starobinets. The English translation, by poet and translator Katherine Young, will can be pre-ordered from Slavica in the US with a September 2020 release date. (UK rights are still available). In Look At Him, Starobinets unflinchingly describes what happened after a routine scan in 2012 revealed that her unborn child had a fatal congenital condition, tracing her subsequent hunt for compassionate clinical care in Russia and in Germany, and the aftermath of her decision to terminate the pregnancy.

Accuracy: This book is searingly accurate. In the first, main section, Starobinets rigorously documents her own changing emotions – shock, hysteria, fear, irrationality, guilt, panic attacks, grief, grief, grief. The second, shorter half of the book consists of interviews with medical staff (all German – no Russian clinicians would respond to her questions) and with mothers who suffered stillbirths or late-term medical abortions. This section closes with two pages of statistical tables, already out of date, contrasting numbers of pregnancy terminations in Germany and in Russia.

Starobinets explains her son’s condition (multicystic dysplastic kidney syndrome) and how it causes death (the useless swollen kidneys crowd the abdomen and prevent the lungs and other organs from developing, so the baby can’t breathe independently). She explains what quickening feels like, and the emotional paradox of continuing to nurture a foetus after setting a date for termination. She describes how the Russian medical system, public and private, routinely disempowers parents and makes no provision for grief counselling; she shows how doctors at the German clinic she attends (in order to assure a humane termination for the baby) treat both parents with compassion and empathy. She documents her own fear and hesitation over seeing her son after the birth (the book’s title is adapted from her German midwife’s advice). But Starobinets is, almost inadvertently, equally insightful on the attitudes of those who mistreat her: the tyrannical cleaning lady who tries to stop her from using the outpatients’ toilet because she doesn’t have overshoes on; the austere doctor who starts calling her sixteen-week baby a ‘foetus’ and her pregnancy a ‘thing’ after confirming the diagnosis, and who then invites fifteen medical students into the room without even seeking Starobinets’ consent, as he continues the intravaginal examination; another doctor who yells at the weeping lady for seeking a second opinion. The most disturbing insight of that whole awful day, one feels, is her second brush with the cleaning lady after leaving the doctor: ‘She silently casts a glance at me, and an entirely sincere, somehow even childlike expression of malicious pleasure spreads over her face. I don’t know how I look. Very bad, I have to think’.

Style: The translation is excellent; Young follows Starobinets’ transitions between medical jargon, lyrical outpouring, and casual slang faultlessly (well, I didn’t like “preggy-weggies”, but I’ve never been a fan of the British English equivalent “preggo” either). The hinge between personal memoir and professional interviews is obtrusive; as a reader, I would have preferred the book to end with Starobinets’ personal story, although I appreciate that she was on a mission to represent other women’s experiences too.

Empathy: Since Starobinets is writing about herself and her immediate family, empathy might be assumed. Yet Starobinets isn’t satisfied to document her own journey. The second, more journalistic half of the book introduces the perspectives of other bereaved mothers, and goes further: re-visiting German clinics, Starobinets asks medical staff what they feel, and how they learned to be kind. We learn how the need for ‘quiet rooms’ where parents could receive bad news, and where they could later spend time with their child after its passing, was first recognized; then researched; and then acted upon with careful attention to architecture, furniture, even lighting to create the right atmosphere for vulnerable parents.

If there is a wider-take-home message for readers of this book (beyond the obvious emphasis on maternal experience, and the need for better care for grieving parents in hospitals and beyond), it is that empathy should never be taken for granted. It can be learned: it must be taught.

Reception: Because Look At Him provoked a whirlwind of startlingly vicious criticism when it was shortlisted for the 2018 National Bestseller (NatsBest) award in Russia (as fate would have it, one of its rivals in the competition was a novel called Look At Me), its Russian reception is worth looking at more closely. In the West, where confessional memoirs are a popular genre, the need for more public discussion about miscarriage, stillbirth, and perinatal baby loss is just beginning to be acknowledged. It is increasingly socially acceptable to include these subjects in female life writing. Caitlin Moran was allowed to write about deciding to abort an unplanned pregnancy as long ago as 2011. In 2018, Michelle Obama helped to normalize miscarriage by writing about her own loss – and, crucially, about its psychological aftermath – in her 2018 memoir Becoming. In literary fiction, there’s still a gap in writing about this aspect of female reproductive experience: Fran Bigman discusses the absence of abortion literature in this excellent article in the LARB.

Neither female life writing, nor public discourse around baby loss, are yet normalized in Russia. Starobinets discovers this at first hand. When Starobinets returns to Russia after the termination, leaving her son behind in a mass grave for infants at the Berlin clinic, she finds her family and friends have formed a ‘solid circle of silence’. Her eight-year-old daughter suddenly stops talking about the subject; later, Starobinets discovered that her own parents had firmly instructed the child never to mention anything about the pregnancy ‘so you can forget about it more quickly’. The extraordinarily negative reaction among some critics, including the NatsBest judges I quote here, implies mass outrage that the ‘circle of silence’ has been broken. The journalist Aglaia Toporova, for example, writes: ‘On a physical level, as a person, as a woman, and so on, I find this text loathsome’, adding ‘it’s vulgar, vulgar, vulgar’. A fellow writer, Elena Odinokova, begins by warning that reading the review will be as unpleasant for the author as reading Starobinets’ book was for her, spends the next 2000 words vilifying Look At Him, winding up (in case anyone missed her point) with the statement ‘I don’t recommend this book to anyone’. A male critic, the music journalist Artem Rondarev, bravely wades into all this female ectoplasm to assert that the book is insufficiently literary and that, while its critique of Russian prenatal care may well be worthy, the author’s over-identification with her text emotionally blackmails readers. The novelist Olga Pogodina-Kuzmina also considered the book un-literary, manipulative, and biased. Here are the top six criticisms of Look At Him, not in any order:

- perpetuating a cliche’d, Manichean contrast between progressive Germany and backwards Russia, particularly in terms of the compassion shown to parents by each country’s medical system (Odinokova, astonishingly for me, argues that Russian doctors don’t show empathy because they don’t waste time expressing insincere feelings; German doctors utter polite formulas because they’re terrified of malpractice suits. “Russian doctors aren’t paid to have heightened ethical sensibilities”, she asserts).

- suggesting that a foetus, particularly one incompatible with life, deserves to be classified as a child (in an extraordinary passage, Toporova assures her readers that she “really has the right” to judge this text, because she lost her own almost-four-year-old daughter to meningitis and grief for ‘a fragment of a woman’s body’ cannot compare; even more perplexingly, Toporova points out in passing that her daughter was also the granddaughter of Viktor Toporov, a founder of the NatsBest award, apparently in order to demonstrate that her right to grieve and right to judge are equally unassailable). Other critics who cite this argument present a more reasoned argument, suggesting that right-to-life campaigners and extreme Orthodox groups could abuse this argument to restrict a woman’s right to abortion.

- not having a traditional literary structure

- having the nerve to expect a happy ending (life happens – get over it)

- talking about herself ( = abusing first-person narrative to manipulate the reader)

- insensitivity to others (seriously: both Odinokova and Rondarev take issue with what they consider Starobinets’ dismissive critique of Russian medical professionals, and of other women with healthy pregnancies, whom she calls beremeniushki (translated by Young as ‘preggy-weggies’). For Odinokova, this failure of empathy on Starobinets’ part amounts to ‘intellectual segregation’. This is to doubly miss Starobinets’ point: far from being a bitter egotist dehumanizing other social groups, she recognizes (and protests) her own instant relegation by medical staff, friends, and even other expectant mothers from the status of a happy, well-cared-for pregnant mums to a failed patient, a mere medical curiosity. And ‘preggy-weggies’ is a self-chosen term Starobinets plucks from a mums’ chat group.

Among this chorus of detractors, the assertion by leading critic Galina Yusefovich (of Meduza) that Look At Him is a ‘classic witness-text’ and ‘compulsory reading’ for men and women alike, sounds almost lonely.

I have discussed the Russian reception of Look At Him at such length not to dwell on its negativity (some of these criticisms are clearly unbalanced) but in order to assess the cultural grounds for dismissing Starobinets’ book. The readers who savage this book as self-indulgent, manipulative, and/or self-indulgent are themselves mostly young or early middle-aged women, educated, urban, and intellectually sophisticated – precisely the same cohort which, in the West, welcomes and indeed produces female life writing. Why, then, are these modern Russian women so keen to perpetuate the ‘circle of silence’ from which Anglophone discourse has so recently emerged? And are their reasons necessarily illiberal, or more complex? Now that Look At Him is available in English translation, it will be interesting to compare their reactions with those of Anglophone critics (one early review calls it ‘compelling and human’).

I have discussed the Russian reception of Look At Him at such length not to dwell on its negativity (some of these criticisms are clearly unbalanced) but in order to assess the cultural grounds for dismissing Starobinets’ book. The readers who savage this book as self-indulgent, manipulative, and/or self-indulgent are themselves mostly young or early middle-aged women, educated, urban, and intellectually sophisticated – precisely the same cohort which, in the West, welcomes and indeed produces female life writing. Why, then, are these modern Russian women so keen to perpetuate the ‘circle of silence’ from which Anglophone discourse has so recently emerged? And are their reasons necessarily illiberal, or more complex? Now that Look At Him is available in English translation, it will be interesting to compare their reactions with those of Anglophone critics (one early review calls it ‘compelling and human’).

The Pregnancy Test‘s Verdict: A lacerating book, by a brave author. Read it, and grieve.

Notes: Thanks are due to Katherine Young, the English translator of Look At Him, for sharing her translation with me. The striking cover image by artist Ghislaine Howard is included in the Foundling Museum’s current Portraying Pregnancy: From Holbein to Social Media exhibition.