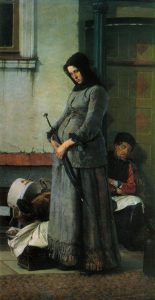

The woman in this picture doesn’t need to take a pregnancy test. It’s obvious that she’s at least six months pregnant, and equally obvious that this child is one of the latest disasters in a life that has recently had too many of them. Her clothes are old; her husband has collapsed, asleep or drunk; their shabby belongings are piled against a wall. We don’t need the picture’s title, Vygnali (“Driven Out”) to understand that this family has been made homeless. Playing with words, we might assert that her pregnancy is a test; a test which confirms that she and her husband and child are doomed to hardship and suffering. The most conventional reading of pregnancy, in literature as in art, is as a symbol of hope and renewal. Here, we “read” this woman’s pregnancy as confirmation of a ruined life.

This 1883 painting by the Russian realist artist Nikolai Yaroshenko is a visual text which encourages a particular reading of pregnancy. In The Pregnancy Test, my guest contributors and I will present and discuss primarily written texts from literary fiction which also promote specific readings, or understandings, of what it means to be pregnant, or to give birth, or to miscarry a child, among other representations of mothering known collectively as ‘maternal fictions’. The way that authors write about pregnancy, as well as about other maternal experiences, influences both how we read pregnant women and the ways we imagine mothers should behave. And not just how we read, or judge, women characters in literature, or images of women as in “Driven Out”, but how we react to real women, sharing our culture, living in our world. Our views about maternal behaviour are informed by the written word.

Sometimes this is obvious, as when on 23 January 2017, President Donald Trump (in the presence of an entirely male staff, including Reince Priebus, Peter Navarro, Jared Kushner, Steve Bannon and others) reinstated the so-called “Global Gag Act” (or Mexico City Policy) for the second time since its introduction in 1984. This is a law which prevents American foreign aid funds from being distributed to organizations which offer women family planning counselling. (Note that American aid funding for foreign abortion clinics was categorically excluded in 1973 under an amendment (to the Foreign Assistance Act) authored by Senator Jesse Helms, a conservative Republican and man.) The total absence of women was much remarked on, as a Huffington Post journalist commented, “There’s something missing from this picture”. That was a very literal enactment of men narrating women’s bodies, or rather, a verbal act by a man (Trump’s signature on the executive order) which will directly affect the physical experiences of women.

But the written word can also affect women’s behaviour in more subtle ways, influencing not only their behaviour but their expectations of themselves; our preconceptions of what’s safe to show and what’s permitted to share. In my own area of expertise, Russian literature, the literary discourse of maternity has been historically monopolized by a few very successful, very influential male writers. Authors such as Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, and Chekhov have narrativized maternal experience such as miscarriage, pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding – with dual effect: firstly, they project images of maternity that fit their own ideological or aesthetic agendas, and secondly, they inform the cultural perception of maternity among readers for generations to come. This trend for male writers to dominate the discourse of maternity continues to the present day throughout world literature: a limited number of writers have formed millions of readers’ ideas about female sexuality and parturition (Madame Bovary as the bad, because desiring, mother; Faulkner on backroom abortion; Caesarean section with Hemingway). It’s even more apparent that certain discourses linked to maternal experience are either rarely described, like abortion, or completely shunned, like menstruation (the best-known, and arguably least helpful, novel on this topic possibly being Stephen King’s Carrie).

This is why I decided to write The Pregnancy Test. Each post briefly “tests” one fictional story or novel by a given author, reviewing it for accuracy, empathy, readability, and intention. See here for more details. There are no limitations on genre, time period, or the author’s gender: the only condition is that every post reviews an example of “maternal fiction”, that is, a text about maternal experience. Later, we hope to organize posts by category, but right now it’s a free-for-all, with our first posts ranging in topic from medieval lais to the highly contemporary fiction. If you’d like to propose a review for a post, contact us on Twitter at @test_pregnancy .