Translated from the Spanish by Megan McDowell (Oneworld, 2017)

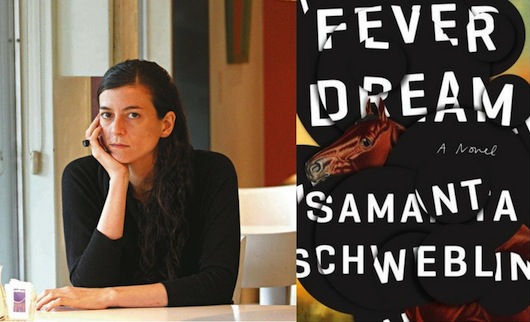

Usually I think that the phrase “I couldn’t put it down” is just a figure of speech, but in the case of Fever Dream it sums up my reading experience. I read it in one sitting: it’s disturbing, terrifying, and absolutely mesmerising. Fever Dream was shortlisted for the 2017 Man Booker International Prize, and was Argentine author Samanta Schweblin’s debut novel (though she has previously published short stories). Published by OneWorld in 2017, it epitomises OneWorld’s commitment to seeking out “emotionally engaging stories with strong narratives and distinctive voices”, and Megan MacDowell’s powerful translation sweeps along with an almost hypnotic urgency.

Fever Dream is a frighteningly real supernatural tale, in which fear and suspense are built up by what we are left to imagine just as much as by what we are shown. The text is made up of a dialogue between a woman lying in a bed in an emergency clinic, and a boy sitting beside her, asking her questions. The boy is insistent that they find out about “the worms” and “the exact moment”, and the woman tells a story that is at once meandering, owing to her confusion, and urgent, as she has very little time left. There are only four main characters in this short novel: two mothers and two children. Amanda, the woman lying in the hospital bed, had brought her daughter Nina on holiday from Buenos Aires to the Argentine countryside (a bleak landscape of seemingly endless soy fields), leaving her husband working in Buenos Aires. Nina is a small and adorable child who Amanda needs to protect from something dreadful, the threat of which has been hanging over her not just since the beginning of the narration, but her whole life: “My mother always said something bad would happen. My mother was sure that sooner or later something bad would happen, and now I can see it with total clarity, I can feel it coming toward us like a tangible fate, irreversible.” This premonition feeds the narrative, and the narrative feeds off it, putting inevitability and presentiment at the forefront of Amanda’s story.

The third character is Carla, who lives next door to Amanda’s holiday rental cottage. Carla tells Amanda a disturbing and supernatural tale of how at the age of six her angelic son, David, escaped death by poisoned water through a process of “transmigration” so that his soul is now partly in another body and she is left with a “monster” in place of her beloved only child. The final character is David himself, now twelve, who is sitting on the hospital bed urging the narrator to tell the story of what happened so that he can pinpoint the exact moment that the “worms” entered her body and changed the course of her life.

The “fever dream” of the title is recounted by Amanda, in something akin to real time, in that it is told in the present tense, but narrates something that happened in a recent past (David tells her at one point that she has been in the feverish state for two days): “I don’t remember much else, that’s all that is happening.” A feeling of somnambulant terror prevails: the immediacy of the present tense in both the dialogue and the dream suggests that this dream could go anywhere, change at any moment, but that the dreamer has no control over its course. Alongside the recounting of the dream is Amanda’s awareness of the real-life situation she is in: lying in bed in a clinic, wondering where her daughter is, knowing she has very little time left. She is also aware that David is not answering her questions but rather probing her with his own, determined to reach a conclusion that he deems to be essential but which to her is “unhelpful” and “missing the most important information.”

“David is a terrifying prompter… mercilessly pushing Amanda on towards an event that will explain why she is lying in a clinic with her life spilling out of her, and which will explain what happened to her child.”

David is the only one who seems to have any control: he decides what is important and what is not, which details can be skipped over and which must be recalled in all their minutiae. David guides Amanda through the labyrinth of her own memory, but at times it seems as though David could change the course of the dream at any moment: “What is Nina doing? She’s such a pretty girl. What is she doing? She walks away a little. Don’t let her walk away.” However, when Amanda attempts to take control of the course of the narrative, it all spirals away: David tells her that she is focusing on the wrong things, and we see a sinister echo of the “thing” that happened: while she was looking away, focusing on something else, the “thing” came in.

Writing for The Guardian, Chris Power opines that “Paradoxically, this is a book only parents will feel the full impact of, but that impact is so great you don’t want to recommend it to anyone with young children.” Indeed, I have to admit that this was an uncomfortable read as a mother of young children: the insistence that it is in trying to protect a child from the danger we can see that we fail to notice the real danger taps into my innermost fears (though I think that might be the point), and the constant references to the “rescue distance” between mother and child (the importance of the rescue distance is evident in the novel’s original title, “Distancia de rescate”) become a painful refrain that goes from conceptual to physical as the nightmare gallops towards its inevitable conclusion:

“Why do mothers do that?

What?

Try to get out in front of anything that could happen – the rescue distance.

It’s because sooner or later something terrible will happen. My grandmother used to tell my mother that, all through her childhood, and my mother would tell me, throughout mine. And now I have to take care of Nina.

But you always miss the important thing.

What is the important thing, David?”

David sidesteps the question, of course. We keep being reminded (by David) that time (Amanda’s time) is running out, and that some secret must be revealed before her death. Yet David seems to know already what happens: Amanda has repeated her story several times, and sometimes he pre-empts what she is going to remember: “In a few minutes, Nina will be left alone in the car.”

Let me be clear: I don’t like horror stories. I’m one of those people who will turn the lights on and check every corner of the house if I’ve read or watched anything remotely frightening. I should have hated Fever Dream, but I couldn’t. I couldn’t, because it’s so clever, and so perfectly terrifying. It goes far beyond dystopia, and into the realm of nightmares, yet it all feels so real, so possible, so recognisable from the powerlessness we know from our own nightmares: “I wonder if Nina is following us, but I can’t turn to check or ask the question out loud.” The construction of the book is striking: it’s a dialogue, but really it seems more like a monologue narration with a prompter getting it back on track when lines are forgotten, and telling both Schweblin’s protagonist and her readers what is and isn’t important, what is worth describing in detail and what can be glossed over. David is a terrifying prompter, though, mercilessly pushing Amanda on towards an event that will explain why she is lying in a clinic with her life spilling out of her, and which will explain what happened to her child.

There are ambiguities in this novel, but they are there deliberately, to destabilise, and to bring you into Amanda’s fever dream where reality and fantasy collide in brutal ways. While my description may make you think that David is an inexorable harbinger of doom, there is also something he is trying to lead Amanda towards, something he wants her to know before the rope that determines the rescue distance is broken. And when you find out what this “something” is, it will tear down the walls around your heart.

Fever Dream is both a reflection on – or a warning about – environmental damage, and a terrifying story of power and pain, loss and love. The relentless landscape of the soy fields and the repeated mentions of “poison” could make this a dystopian warning about genetic modification, but at the forefront are the entwined stories of two mothers and their love for children they are, ultimately, powerless to protect. It’s terrifying, chilling, haunting – everything you’d expect a nightmare to be – but Fever Dream is a brilliant book, a wonderful debut, and not to be missed.