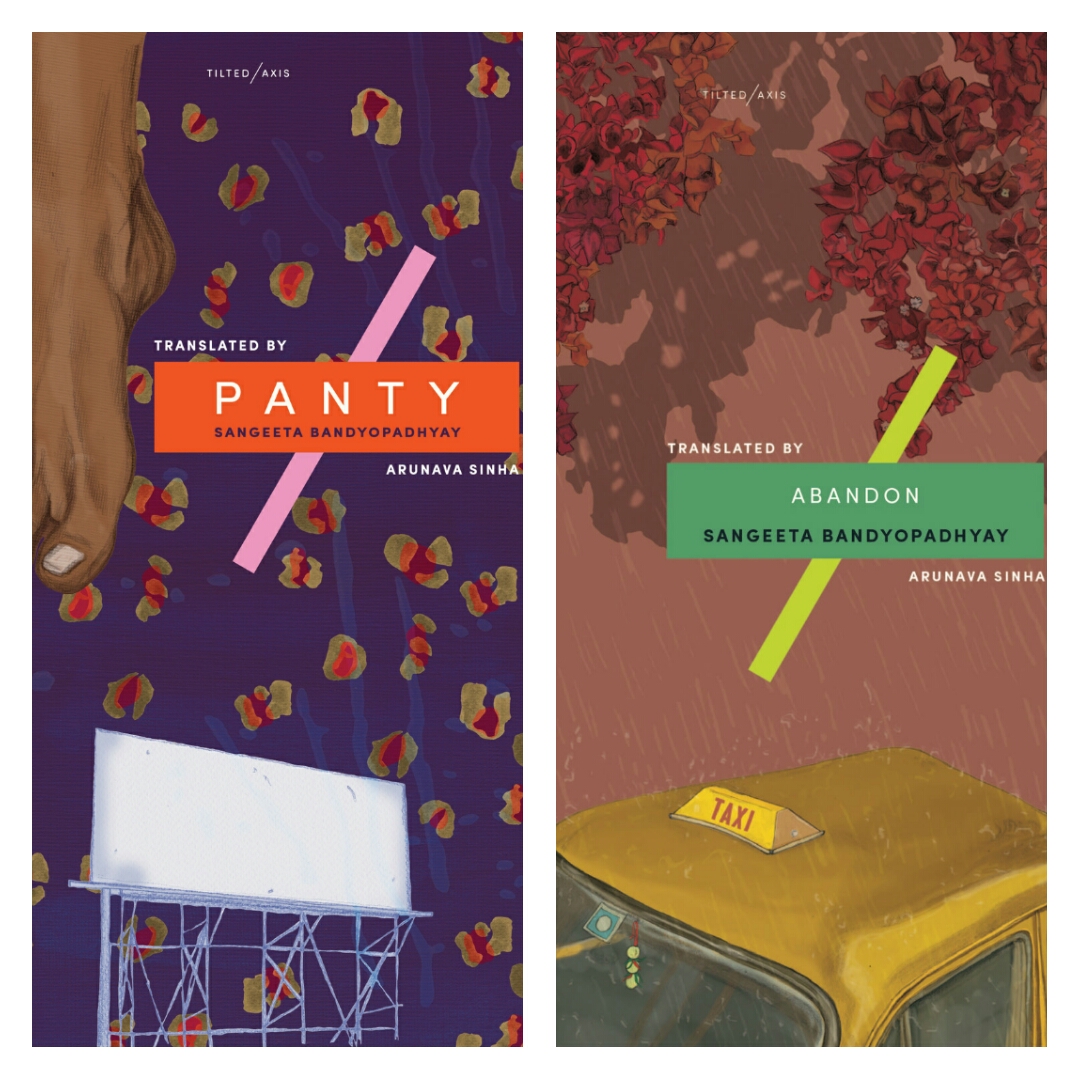

Translated from the Bengali by Arunava Sinha (Tilted Axis Press, 2016 and 2017)

When I first started browsing the Tilted Axis catalogue, I was intrigued by Panty and Abandon by Sangeeta Bandyopadhyay: both novels deal with themes of guilt, duty, sexuality and cultural (non-)conformity, and both present themselves as conscious narratives, playing with story-telling in original ways. Because they have a male translator (Arunava Sinha) they fall outside the parameters of the Women Writing Women Translating Women project, and so I didn’t read them straight away. But earlier this year I read them for my own pleasure, and am writing about them today for yours!

I read Panty first, for no other reason than it was on the top when I opened the parcel, and I’m glad I read them this way round. As soon as I posted a tweet about the two books, several people commented that Panty is good, but Abandon is amazing, and (spoiler) I’m with them. I enjoyed Panty, though, so let’s start with that…

First of all, if you like a linear narrative and a clear plotline, Panty is probably not for you. If you’re happy to be destabilised, to swirl around in circles as different stories unfold simultaneously and in superimposition, then it’s a tremendously fulfilling read. A woman arrives in Kolkata, to an empty and heavily padlocked apartment, and as she is acquainting herself with her new surroundings she finds a leopard-print panty in the wardrobe. She wonders about the owner of this sensuous, shameless undergarment, and when eventually she slips it on, she steps into the sexual memories of the woman who wore it before her. Her own story then ripples out alongside – or enmeshed with – these memories: the reality of a surgery she is awaiting alone and the passion of two bodies writhing in union are brought together in the unnamed woman’s relationship with a man who will not commit to her. Through the memories of the panty’s owner, she discovers what it really is to kiss: “All this time, she’d thought she knew what a kiss was. Just as she’d thought she knew what love was, what the body was, what art was. When in fact she had known none of that.” The limits of her life so far are in stark contrast with the unconditional giving and receiving she experiences through another woman’s memories.

The narration shifts from first person to second person to third person as the stories collapse in on one another, and at times I had to re-read sections to be sure I knew who was speaking (or, at least, to think I was sure). Writing, narration, illness and the body fold together, writing coming from the body (“Was this one line all the blood that would ever flow from the wounds?) and pain being sucked out from the body through passion (“you fit your mouth to her right nipple and suck out all her suffering”) and turned into writing. Panty felt experimental, not rooted in conventional narrative expectations – it is not a snapshot of a life, but an exploration of an experience: introspective, chaotic, and yearning. The structure of Panty is, perhaps, best summed up in this reflection: “I ran away. I escaped to the centre, inside the fire that rages at the circumference of life.” The bodies unfold at the centre of the fire, a circle of flames around past and future, a moment suspended at the eye of the storm.

Sinha’s translation is refined and at times elaborate, but because this is not a novel of gritty realism, it works: though phrases such as “even if we do happen to meet, let there be no flash of recognition in your eyes. Let the portion of your heart in which I exist die this very moment. Let us free ourselves from this bond as far as is possible” would not be out of place in a 19th-century tragedy, they still work here, because it is a story of excess, of pulsing bodies and burning hearts. Trisha Gupta makes an interesting point about the poesy of Sinha’s translation resting on “a style that has a certain lushness and emotional purchase in Bengali, but can sometimes appear long-winded in contemporary English”, but because I cannot (and probably shall never be able to) read Bengali, I rather like that some features of the original language come through in the translation. In fact, in Abandon, one character comments that “there’s no better language than Bengali to pamper someone with”, and so if there is anything intricate in Sinha’s translation, it seems to me that this opens a window to the Bengali beneath the words.

Panty was a brave book with which to launch a new press, and there are some features of Abandon which echo it, particularly in the guilt about neglected children, the challenging of traditional notions of femininity, and the deliberately unconventional narrative style. In Abandon, a young mother runs away from her life and her responsibilities, only to find that her five-year-old son follows her. She is torn between the desire for solitude so that she can write a novel, and the need to protect and care for her son: this polarity of feeling is epitomised by the dual meaning of “abandon” as both neglect and unbridled passion, and in the similarly dual use of narration: “I” for the primal need to care for herself, and “Ishwari” for the mother bound by duty and love to care for her son.

There is a conscious awareness of writing within the narrative: from the opening page, I/Ishwari says that “the taxi begins to move, and with our desperate attempts to seek shelter for the night, a novel begins.” Throughout her narration, she points to incidents that were improbable and therefore part of the structure of her story, characters who are there because the story needed them; she recognises useful narrative devices (such as the occupation of the roof terrace as an ideal space to develop her writing) and consciously lives there so that it can be part of the story. As in Panty, the narrator destabilises the reader with regular reminders that this is just a story, and can manipulate as well as illuminate: “Ishwari’s head was about to drop in embarrassment, but such is the nature of this novel – it is sceptical and trusting at the same time, it tells the truth and also lies.” I/Ishwari repeatedly reminds us that we have chosen to enter her “novel of lies and truths”, and in doing so she exercises the power to lead us wherever she chooses. And yet she herself is powerless in the hands of the narrative force: it is a “predatory novel”, characters enter it because there is not yet anyone like them within its pages, and just as her relationships have always imprisoned her with their needs, so the novel begins to do the same. Ishwari constantly has to choose between her own survival and her son, and her survival seems to be possible only by navigating her way through this treacherous novel which, nonetheless, “understands my agony.”

Creativity and motherhood are seen as incompatible, Roo’s need for Ishwari the only impediment to her unfettered self-expression. Prenatal death is presented as the perfect murder: “When the mother’s womb kills the child, does anyone hold the mother responsible? […] Only mothers can dispense the kind of death neither nature nor civilization can question”, and though Roo has survived into infancy, he is debilitated and weakened, and Ishwari will not allow the same fate to befall her novel. In a book replete with references to gender inequalities in India (beaten wives, “wayward” women, forced sex, submission), I/Ishwari refuses to fulfil a role or meet expectations of womanhood, and yet manages to give the impression that she is doing exactly that. Her job as a companion and caregiver to the sick, grieving Bibaswan outwardly shows her displaying typically “feminine” qualities of nurturing and compassion, and yet when their relationship becomes physical, Bibaswan realises that he has no domination over her mental or emotional presence, only the physical presence that is demanded of her in order to collect her envelope of banknotes. As in Panty, Bandyopadhyay explores women’s independence and sexuality, subverting stereotype and expectation at every turn.

In both Panty and Abandon, the at times confusing, sweeping, spiralling narratives are punctuated by moments of searing beauty. In Abandon, there was one line in particular that took my breath away: “She did not realise that suppressing love is the strongest form of self-flagellation in the world.” Such insights are of the kind that stay with me, that I roll around inside my head and mouth for a long time after I finish reading. Indeed, as I/Ishwari explains, “the more the reader is bruised and upset after entering the novel, the more she considers the reading of it profitable”: Panty and Abandon are not simple, or light-hearted, or easily forgettable. They wound, they subvert, and they challenge – and that is their great triumph.