I’m delighted to welcome a new guest contributor to the blog: Julia Sutton-Mattocks won the 2017 Susanna Roth Translation Competition for her translation of Bianca Bellová’s The Lake, and is writing today about her experience.

Find out more about Julia on our Guest Contributors page.

One of my translation students recently told me that she always saved her translation homework for the end of the week. It would be a treat, she said; something to look forward to when all of the other tasks were done. It amused me, because it was what I had always done too. What’s odd is that, as an undergrad, I never really considered translation except as a language exercise. I’m a grammar geek type of linguist and translation presented a gloriously creative form of grammar puzzle. I loved it, but for some reason it never crossed my mind to take it further.

Fast-forward several years to January 2017, when a Twitter post from Czech Centre London caught my eye. They were inviting submissions for the Czech–English round of their annual Susanna Roth Translation Competition, which they run jointly with the Czech Literary Centre in a number of different countries. The competition aims to encourage a new generation of translators to enter the world of Czech literary translation and is named in honour of the Swiss translator Susanna Roth (1950–1997), who translated the work of some of Czech literature’s best-known names into German. The announcement reached me at an auspicious moment; I was part-way through the second year of my PhD and had recently made a New Year’s resolution to make the most of my PhD years by not focusing exclusively on my thesis (apologies to my supervisors, should they be reading). I decided to give it a shot.

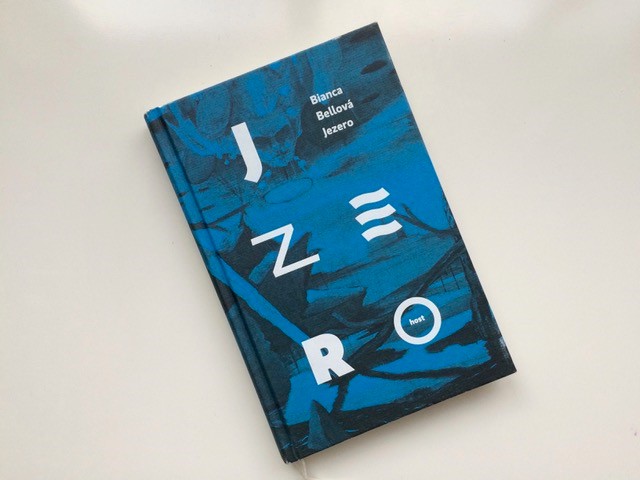

The competition’s focus is on contemporary Czech prose, even the leading lights of which often have to fight quite hard to get translated into other languages. 2017’s chosen text was the opening of Bianca Bellová’s Jezero (The Lake) (Host, 2016). Bellová (b.1970), a Prague-born writer with Bulgarian roots, is a big name in contemporary Czech prose. The Lake, her fourth novel, won the Czech Republic’s prestigious Magnesia Litera Book of the Year award in 2017 and was also one of the 2017 winners of the European Union Prize for Literature. It is a Bildungsroman and was inspired by the drying up of the Aral Sea, but its setting is completely fictional. Certain of the details identify the location as Central Asian, the presence of Russian soldiers indicates a Soviet context, and the sense of change and rupture that permeates the novel suggests that it is set in the late 1980s to early 1990s. Yet there’s nothing to enable the reader to define a precise geographical or historical setting, which makes it a novel of unknowns, disorientating and yet universal.

The competition’s focus is on contemporary Czech prose, even the leading lights of which often have to fight quite hard to get translated into other languages. 2017’s chosen text was the opening of Bianca Bellová’s Jezero (The Lake) (Host, 2016). Bellová (b.1970), a Prague-born writer with Bulgarian roots, is a big name in contemporary Czech prose. The Lake, her fourth novel, won the Czech Republic’s prestigious Magnesia Litera Book of the Year award in 2017 and was also one of the 2017 winners of the European Union Prize for Literature. It is a Bildungsroman and was inspired by the drying up of the Aral Sea, but its setting is completely fictional. Certain of the details identify the location as Central Asian, the presence of Russian soldiers indicates a Soviet context, and the sense of change and rupture that permeates the novel suggests that it is set in the late 1980s to early 1990s. Yet there’s nothing to enable the reader to define a precise geographical or historical setting, which makes it a novel of unknowns, disorientating and yet universal.

The novel opens in the tiny fishing village of Boros on the shores of a rapidly disappearing lake. There a little boy called Nami goes to school, builds treehouses, fears the Spirit of the Lake, pretends to shoot down planes and wonders who his parents are. He has a vague memory of his mother, but has grown up with his grandparents, who avoid all of his questions. Nami later escapes Boros for the city on the other side of the lake, where he meets a cast of beautifully drawn characters: a rough diamond construction worker, Gleb Nikitich; a money-crazed drug dealer, Johnny; the Old Lady (an aristocratic former lover of the deposed autocratic Statesman); and a grumpy escaped monkey named Majmun. Over the course of the novel, Nami’s path is set with tasks to overcome and relationships to build. Only once he has built up his physical and moral strength, and learnt to cope with both love and loss, can he complete his journey to self-discovery.

The extract was a joy to translate; full of colloquial language, juicy grammar problems, odd changes of tense and a lot of different types of food. Tense was a sticking point I encountered early on. Czech tends to use the historic present much more commonly than English, and this extract was no exception. Since I often struggle with the feel of the historic present in English, I initially started by putting everything into the past. Yet the immediacy of Bellová’s prose seemed to be lost as a result. I switched backwards and forwards several times before settling on retaining the present tense narration. Even then, there are short passages of past tense narration in the original, which I eventually came to read as cinematic flashbacks within the main narrative, but which initially seemed specially placed just to throw me.

The extract was a joy to translate; full of colloquial language, juicy grammar problems, odd changes of tense and a lot of different types of food. Tense was a sticking point I encountered early on. Czech tends to use the historic present much more commonly than English, and this extract was no exception. Since I often struggle with the feel of the historic present in English, I initially started by putting everything into the past. Yet the immediacy of Bellová’s prose seemed to be lost as a result. I switched backwards and forwards several times before settling on retaining the present tense narration. Even then, there are short passages of past tense narration in the original, which I eventually came to read as cinematic flashbacks within the main narrative, but which initially seemed specially placed just to throw me.

The various foodstuffs hurled a whole new translation issue into the mix. They provide a snapshot of the decisions I found myself needing to make. The characters in The Lake spend a lot of time eating, making or thinking about food; and they eat, make and think about food from a wide variety of different cuisines. How these were rendered in English would have an effect on the reader’s interpretation of the novel’s setting. The Czech ‘lívanec’ is a thick pancake, somewhat like a scotch pancake, an American pancake or a drop scone. The English ‘pancake’ to me is something more akin to a crêpe, so I didn’t feel I could leave it unqualified. Using the word ‘scone’ for a UK audience conjures up incongruous images of jam and cream; and using either ‘American’ or ‘scotch’ wouldn’t have worked for obvious reasons. In the end, I went with ‘bliny’ since, in English, we tend to think of ‘bliny’ as thick pancakes; and I justified the change on the basis that Russian influences already existed elsewhere in the text and that some would be lost in the translation process for other reasons (the immediate Soviet connotations of the Czech word ‘gazík’, for instance, are lost in my English ‘army jeep’).

Another foodstuff, the Czech ‘cibulový koláč’, I rendered as ‘onion pie’. I felt that retaining ‘koláč’ (or, perhaps, ‘kolach’) would have emphasised the text’s Czechness unnecessarily. However, as I discovered when I discussed The Lake at a translation festival in September 2017, this was certainly an imperfect solution, since everyone in the room had a different idea of what a pie looked like. Then there was ‘burek’. Nami’s grandmother and her neighbour spend a lot of time making burek and I spent an inordinate amount of time reading recipes for it so that I could understand how to translate the scene in question (one day, perhaps, I’ll put this knowledge to culinary use.) Burek (or börek) is a savoury pastry made across parts of Central Asia, the Middle East and the Balkans, so its presence in the text served to emphasise the novel’s Central Asian setting. While I consequently left ‘burek’ in the English, I translated ‘těsto’ (‘pastry’) as ‘filo pastry’ so that readers who didn’t know what burek was had a bit of a clue.

Like my student, I used the task as a treat: if I could do a really good day’s concentrated PhD work, I got an hour or so at the end of the day to translate. It was surprisingly motivating and I was more than a little sad when it was done and dusted. The email conveying the news that I’d won arrived in my inbox on a blisteringly hot May day in Seville. I’d just arrived for a three-day choir tour (welcome to my other life) and was absent-mindedly checking my email while waiting for the keys to my hostel room. The sense of euphoria was extraordinary. It only became more so when I found myself whisked off on the prizewinners’ trip to the Czech Republic in July, courtesy of the organisers, for a week-long whirlwind of seminars, presentations, sight-seeing trips (including to the spectacular UNESCO World Heritage site of Český Krumlov) and a lot of hearty Czech food. The other eight winners (all women) came from Ukraine, Italy, Hungary, Serbia, Bulgaria, Poland, Japan and South Korea, and it was fascinating to talk about the very different experiences we had all had in translating the same text into our own languages and to share our stories about learning Czech.

If, as I hope, I’ve intrigued you, you can download my English translation of the opening of The Lake here. If you want to read on, for the moment you’ll need to turn to the original Czech or to one of the five translations into other European languages that have been published in 2018 (see bottom of page for details). For more of a Bellová fix, or just to read more Czech literature in English translation in general, the latest issue of the quarterly online journal Apofenie is a good place to turn. Four times a year, Apofenie’s all-female editorial team curates a selection of contemporary artwork, poetry and prose from around the world in original English translations. Their latest issue, which focuses on Czech literature, includes my translation of Bellová’s short science fiction story ‘Závrať’ (‘Vertigo’, 2014), as well as translations of works by other leading lights of contemporary Czech prose, including the women authors Alena Mornštajnová, Jana Šrámková and Lucie Faulerová. For the really keen, even more information in English about contemporary Czech literature can be found at Czech Literature Online, a project financed by the Czech Ministry of Culture and managed by the Czech Literary Centre. Happy reading!

The Lake is now available in the following European languages (all 2018 publications):

Dutch: Het Meer, De Geus, trans. by Kees Mercks

French: Nami, Mirobole éditions, trans. by Christine Laferrière

German: Am See, Kein & Aber, trans. by Mirko Kraetsch

Italian: Il Lago, Miraggi, trans. by Laura Angeloni

Polish: Jezioro, Afera, trans. by Anna Radwan-Żbikowska

The 2019 round of the Susanna Roth Award is now open for submissions. To find out how to enter, visit this page.