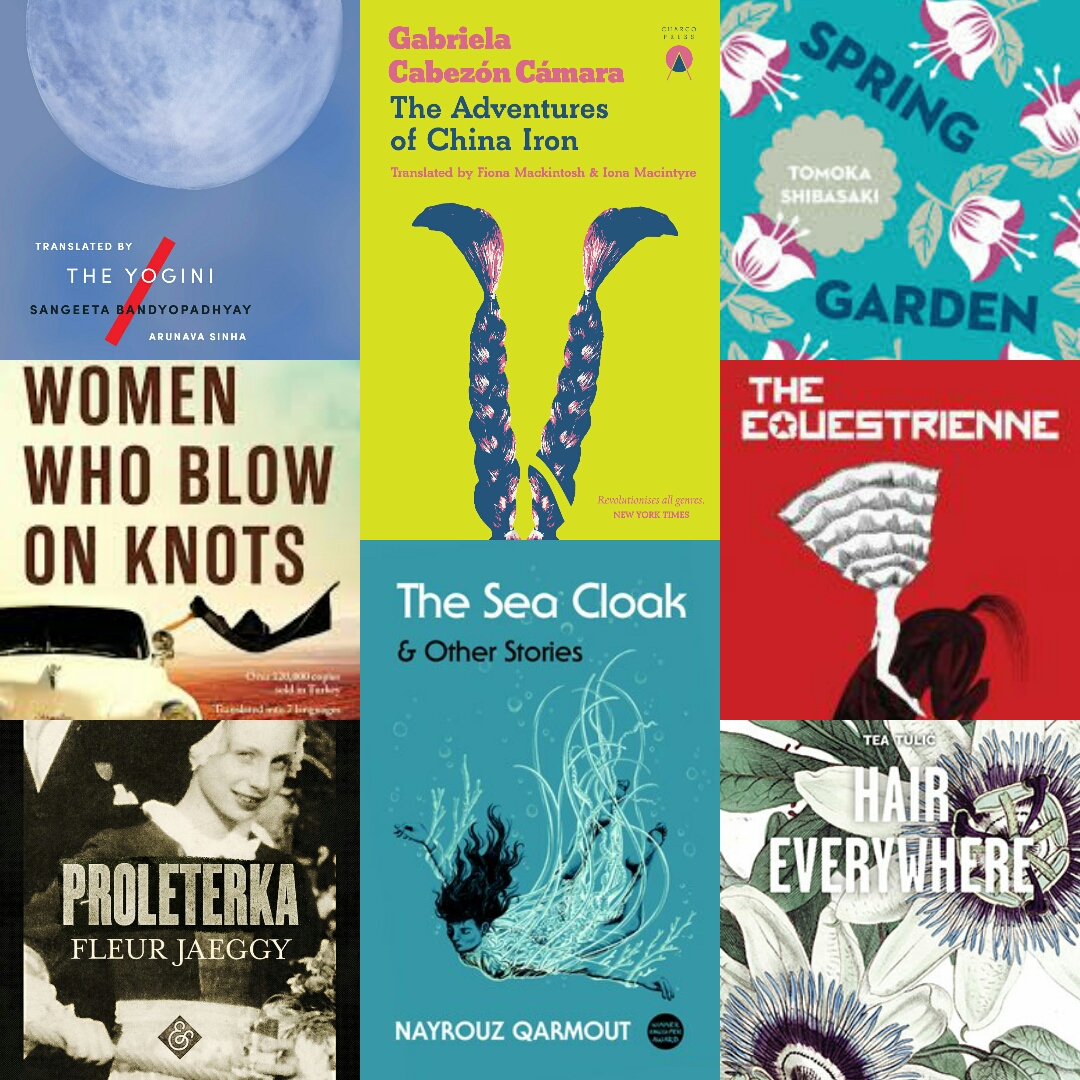

As many of you probably know, August is Women in Translation month, an initiative started and championed by Meytal Radzinski. In honour of this year’s Women in Translation month, here are my thoughts on the eight books I read in August.

Ece Temelkuran, Women Who Blow on Knots, translated from Turkish by Alexander Dawe (Parthian Books)

In Women Who Blow on Knots, four women escape and find their shifting fate(s) on a madcap road trip across the Middle East as the Arab Spring breaks. It’s full of action, cliffhangers and social comment, and maintains a lightheartedness while dealing with weighty issues regarding women’s roles and representations in the Middle East. The title is from a sura from the Qur’an that refers to witchcraft, and there is indeed something mystical about this story. There is something of the cinematic too: several of the implausible feats pulled off by the larger-than-life Madam Lilla felt like a film in the sense that the hows and whys of breathtaking turns of events are edited out in favour of the more watchable final result. The characterisation is what stood out for me the most: though the three younger women could easily have fallen into stereotypes or tropes of femininity, Temelkuran invested each of them with heart, fallibility, and a destiny that each must fulfil in her own way.

Sangeeta Bandyopadhyay, The Yogini, translated from Bengali by Arunava Sinha (Tilted Axis Press)

The latest release from Tilted Axis Press is an absolute gem: Sangeeta Bandyopadhyay’s third novel The Yogini is a tale of fate, illusion and self-destruction, offered in a sumptuous translation by Arunava Sinha. Homi is a young woman who, on the face of it, has everything she could wish for: a high-powered and exciting job, a full life, and a passionate marriage. However, a chance encounter one day with a silent man with matted locks imperils everything she holds dear, as fate “sinks its claws into her” and prompts her to reflect on contingency, on choice, and on inevitability. Fate is the driving force of the narrative, stalking Homi and gathering in her heart “like unshed tears.” Merciless and inexorable, fate – or is it her own will? – guides and pulls Homi through increasingly self-destructive situations, until she risks exiling herself from happiness and losing everything that ever meant anything to her. Powerful, explosive, and utterly compelling.

Nayrouz Qarmout, The Sea Cloak, translated from Arabic (Palestine) by Perween Richards (Comma Press)

Regular readers will already know how much this book moved me, from my review last month. Nayrouz Qarmout is a Palestinian author writing about life – and particularly women’s lives – unfolding on the Gaza strip. Expect a violence that has become commonplace, but also a universal experience that is utterly irresistible: Qarmout writes with warmth and compassion, never instructing but always teaching. The translation by Perween Richards revels in the richness of language to convey all of the atrocity and humanity with which Qarmout’s writing swells: these are stories of the everyday violence, restriction and terror of living in Gaza, but above all they are stories of everyday humanity. This one is not to be missed, and is one of my top recommendations of 2019.

Ursula Kovalyk, The Equestrienne, translated from Slovak by Julia Sherwood and Peter Sherwood (Parthian Books)

Set in 1984, The Equestrienne is a coming-of-age story about two misfit girls, “dangerous bitches, disruptive females who disregarded all the rules.” The girls forge their future in a riding school in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic, and the narrative combines the personal story of identity and survival with comments on socialism vs capitalism (“we swapped our barbed wire cage for one made of gold.”) I was a little surprised by this novella, as it wasn’t quite what I was expecting (though that’s not a bad thing): I thought it would focus on the elderly character looking back on a life narrated in flashback, but on reflection it works better as a coming-of-age story. I also very much enjoyed the collaborative translation by Julia Sherwood and Peter Sherwood; every word is perfectly placed.

Tea Tulić, Hair Everywhere, translated from Croatian by Coral Petkovich (Istros Books)

This book was longlisted for the Warwick Prize for Women in Translation in 2018, and I’ve been meaning to read it since then. I came to it after having enjoyed a recent release by Istros Books (Singer in the Night, reviewed here), and Hair Everywhere is harrowing and challenging, but well worth the read. Tulić offers a fragmented narrative about one family coming to terms with cancer, following their daily life after the mother is diagnosed with an aggressive tumour that will ultimately kill her. By turns delicate and brutal, it’s also a story of female legacy: “While I watch her lying in bed, I can feel the umbilical cord between us. Something I have tried to cut a thousand times already. And now I hold onto that invisible cord as though I were hanging from a bridge.” As well as a reflection on loss, this is also a lyrical hymn to love and a painful testament to our failure to love enough before it’s too late.

Fleur Jaeggy, Proleterka, translated from Italian by Alastair McEwen (And Other Stories)

This is the third of Fleur Jaeggy’s novels to be published by women in translation champions And Other Stories, and in it a teenage daughter dissects her emotionless relationship with a father she barely knows. The girl and her father embark on a cruise to Greece, aboard a ship called the Proleterka: this is their “last and first chance to be together,” during which the girl experiences a violent sexual awakening and an increasing neglect of her father (some children, she reminds us, “have the gift of detachment.”) Jaeggy’s examination of relationships strikes a skilful balance between perspicacity and silence: every word seems to have been weighed before being offered, and McEwen ably renders this in the transation. An unsettling narrative that cuts like a razor.

Gabriela Cabezón Cámara, The Adventures of China Iron, translated from Spanish (Argentina) by Fiona Mackintosh and Iona Macintyre (Charco Press)

I was able to get an advance copy of this forthcoming title from Charco Press at Edinburgh International Book Festival, and I can only urge you to read it as soon as it is available. This is an epic and subversive dialogue with Argentine history and literary canon: told from the perspective of China, the abandoned wife of José Hernández’s eponymous gaucho poet Martín Fierro, The Adventures of China Iron reinscribes female experience in a male-dominated context. With a luscious and rhythmic prose, Cabezón Cámara subverts and queers one of Argentina’s great literary texts in an unforgettable journey across the pampas, but also offers profound reflections on industrial progress, women’s experience, colonialism, and sexuality. Fiona Mackintosh and Iona Macintyre truly entered Cabezón Cámara’s universe, and have translated the cadence and atmosphere of the text beautifully.

Tomoka Shibasaki, Spring Garden, translated from Japanese by Polly Barton (Pushkin Press)

This Japanese novella is an unhurried tale of quiet obsessions and missed opportunities that nonetheless manages to maintain suspense: divorcé Taro lives in a condemned block of flats, and meets his neighbour Nishi, who is obsessed with the sky-blue house across from their block. Little by little this obsession starts to take over Taro’s life too, as the story edges towards a conclusion overshadowed by the threat of demolition. Will Taro and Nishi uncover the secrets of the house before they have to move away? Will they allow themselves to fall in love before they are separated? An excellent translation by Polly Barton manages to convey the wistful yet tense heart of the story.