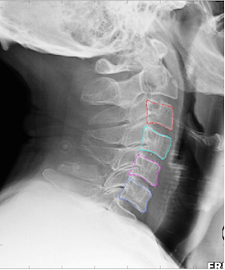

Patient and public involvement (PPI) in health research is defined as research being carried out ‘with’ or ‘by’ members of the public rather than ‘to’, ‘about’ or ‘for’ them. (INVOLVE, https://www.invo.org.uk/find-out-more/what-is-public-involvement-in-research-2/). Our seed corn projects are increasingly including PPI or public engagement activities in their plans, and Karen Knapp’s project is no exception. The project, entitled ‘Computer Surveillance Program in Neck Injury Evaluation: the CSPINE Study’ aims to develop a new computer programme that can help healthcare professionals diagnose neck injury correctly and quickly.

The project team wanted to hear the opinions of patients and members of the public around the concept of computers assisting the diagnosis of neck injury in the emergency setting. Would this be acceptable? Would they have concerns about artificial intelligence (AI) assisting doctors making a diagnosis? They also wanted to hear more about the experiences of those who have had neck injuries, in particular around diagnosis, treatment and potential improvements. The workshop was held on 21 March, and we had a mixture of attendees. Some people had experience of (sometime multiple!) neck injuries, whilst some didn’t. The first part of the workshop focused on introducing the research, and for the second part we split into two groups to discuss the concept and to hear the patient’s experience of diagnosis and care. Overall, discussions were interesting and useful, with most attendees agreeing that the software would be acceptable to use in making a diagnosis, as long as this was aimed at supporting a clinician’s decision rather than aiming to replace this. Some members of the group suggested ideas to take the research further and how it might be used to support diagnosis of neck injuries in developing countries.

Here is what the project team and a medical student had to say about their experience of the workshop:

Jack

In terms of using AI for diagnosing neck fractures, people were fairly insistent on it being part of a supervised process, such that there was still an expert involved throughout the process. This led to some interesting discussion about how best to incorporate software of this type into the clinical pathway. The workshop will certainly help refine how I explain/present the software to the public, based on the subsequent discussion. It might have been better to have a different structure in the group sessions to help overcome the reluctance of some people to contribute, but generally the feedback was very useful.

Jude

The workshop was a really useful exercise to hear other opinions on our project. Two things stood out for me. One was the debate about whether, if the software was used as part of a diagnostic pathway, patients would need to know that the software was being used to help clinicians make a decision. The second was the development of the idea that Karen briefly mentioned about using the software in developing countries where CT scanners and radiologists may be scarcer. Some ideas developed from the participants and researchers about the possibilities and challenges of implementing this.

Joel

It was good to talk with lay people about the project, as this made me think and gave some ideas on how to develop the project, which I might not have had simply talking with colleagues. Someone also mentioned testing the software on cases that were misdiagnosed, to see if it would have helped. It was also good to hear that people are happy about the use of AI to help with diagnostic — as long as the AI does not replace the expert radiologist.

Karen

I thoroughly enjoyed the opportunity to discuss this project with the workshop attendees. I was pleased to see how open they were to AI being incorporated into their diagnostic pathways and they were so positive about the project and potential benefits to patients. While being keen, the group also raised the need to fail-safes to be built in. There was large concern about computers making a diagnosis without human involvement and they wanted to ensure that the software was used to prevent missed diagnoses. Therefore, the software needs to ensure that the doctor or radiographer makes a diagnosis before using the software to double check. We will use their feedback to help build software which is acceptable to patients as well as hopefully improving outcomes.

Naomi

I attended the CSPINE patient public involvement workshop as a medical student involved in research to see how the group was run and how the views of non-researchers could be gathered and incorporated into research. I did not know what to expect as I thought this topic seemed quite technical and not very accessible to the public. I was surprised by how quickly the group got to grips with the technical aspects of the project after a short introduction to the rationale for development and a brief look at the software’s capabilities so far. Participants shared personal stories and experiences which provided a great springboard for others to see the current challenges and therefore value of an additional tool to help in diagnosis in this area. Both the researchers and the members of the group seemed to get a lot out of the discussions. I think there is potential for the public to feel intimidated by “experts” and people can feel confused and vulnerable up against them, however the atmosphere that was created in the room felt quite empowering for the patient/public group as it was clear their opinions and experiences were being valued and bringing a new perspective to the project. In addition, I could see how the researchers having to discuss what they were doing with the patient/public group in a different way to how they had previously been communicating it to other academics allowed them to see their own work in a new light. The patient/public group had great vision about the future application of the software and the practicalities of implementation and integration to routine use which felt very motivating.