This site was funded by

Introduction

Employing the principles of universal design means considering the accessibility of programmes and modules from their inception and making accessibility and flexibility an intrinsic part of their design.

As was covered in section 2 ‘The law, the University’s rules and theories of disability’ there are cases where it is not possible to create modules and programmes that are completely accessible to everyone, but these cases are rare, and we need to carefully consider whether knowingly having an inaccessible component in a programme can be justified.

In very broad terms, programmes are accessible if there are no barriers to entry, participation, progress and completion of a module or programme for students with impairments. If this is not completely possible then no need to be sufficient flexibility in the activities and assessment methods, so that reasonable adjustments can be made for students with impairments. For example, if a module requires students to demonstrate ‘listening skills’ or be able to interpret visual images, these requirements will create barriers to students with limited vision or hearing. It would be preferable to have all such requirements removed from a module, where this is not possible, alternative assessment criteria will be needed for students with these impairments. It is not sufficient to rely on individual students being given ILPs and individual accommodations. See the section on Accessible course design for further examples of ILOs that may create barriers for students and examples of alternative ILOs.

Additionally, the nature of the programme requirements must be explicit, so that students with impairments can determine themselves whether they would be able to successfully complete all of the required components.

It may be the case that students with disabilities are more intellectually able than their classmates as they have been able to gain a place in HE dispite of the barriers they have faced. However, some of the coping strategies students with disabilities have employed may have involved simply avoiding classes or modules which are taught or assessed in a way that the student feels daunted by. Butler (2013) reports cases of students with stammers avoiding modules with presentations or not attending seminars where there is an expectation of student participation and accepting any consequent reduction in their grades. With a very few exception (where professional competences are required) we should aim to make all of our programmes and modules accessible paying particular attention to compulsory and non-condonable modules.

The principles of backward design

Many proponents of UDI advocate the use of ‘backward design’ where the design of modules and programmes begins by determining the ultimate objectives or learning outcomes for a module. They then work backwards from the ILOs to determine the best, and most inclusive methods, through which such outcomes might be achieved. For example, if an ILO stated that a student should be able to understand how a particular piece of equipment works, using backward design one would first ask does a student need to simply understand how the equipment works or must they be able to physically use the equipment themselves. As using equipment might be difficult or impossible, for students with a number of impairments, we should first consider whether this is an essential ILO or whether an alternative could be considered. The module convener might then consider how this might be best taught; would a verbal or written description of how the equipment be sufficient, or would the equipment be better demonstrated. From an assessment point of view, must the student have to physically use the equipment? If the student does need practical experience of the equipment, could this be assessed by having the student give instructions to an educational support worker if the student has limited fine motor control? Alternatively, is this an activity that a student must undertake individually or could students work in groups so the activity can be completed collectively?

Similarly, if a module or programme’s ILOs state that a student needs to be able to carry out physical tasks such as taking measurements, recording data or making field notes, are there alternatives that would be acceptable for assessment purposes? For example, could students submit verbal recordings, rather than written, field notes? Could a phenomenon be explained rather than drawn?

Clarity of both module objectives, and the methods used to achieve those objectives, will help both impaired and non-impaired students to make informed choices about whether or not they will be able to succeed on the module.

Multiple means of presentation

Another way in which we can make teaching accessible is to present information via a variety of means, as this enables students to access information in the ways they find most accessible to them. Most modules will already do this in lectures by providing presentation slides in addition to the spoken lecture, through tutorials, step-by-step demonstrations, discussions and material posted on the online teaching environment. Be aware however that some media are not compatible with assistive software, for example material that has been scanned may cause problems for screen readers.

Orr et al. (2009), quoting Rose et al. (2006) say that ‘faculty may intuitively recognise the potential benefits of such inclusive teaching practices, and yet lack the understanding needed to bring these concepts to fruition in the classroom’. We hope the following guidance will help staff to adopt and apply inclusive teaching practices.

Programme and module design

There are four primary accessibility considerations when creating a programme; we need to ensure that there are no barriers to entry, participation, progression and success.

Current UoE Programme Specification Template with guidance

Guidance from Universities UK’s (2015) ‘Student Mental Well-being in Higher Education Good Practice Guide’ states that courses should design-in accessibility. This approach is applicable to all impairments.

“Institutions should consider the applicability and implications of their student mental health-related policies and procedures in respect of arrangements with collaborative and other partners such as further education colleges, placement providers, schools and employers. They should also consider opportunities for joint action with partner institutions and bodies.”

“It is recommended that institutions have a wide range of policies available to cover the diverse needs of their students, in order to support their progress through their course as effectively as possible. When temporary withdrawal is considered the best option, these policies should enable students to return to their course with support in place. It is also recommended that fitness to study procedures contain appropriate provision to enable a student to request a return to study”following a required withdrawal.

Entry requirements

If students are admitted to a programme using normal university procedures via UCAS then there are unlikely to be barriers to entry. However, you may wish to consider English language competency levels for students who are hearing impaired. Applicants who are British Sign Language users will have English as a second language and so you might want to consider their applications using the criteria for international, rather than domestic students, although they will be unlikely to have a the ability to meet the standard for ‘listening’ skills. Similarly dyslexic students might have English language qualifications that are lower than we might ordinarily accept.

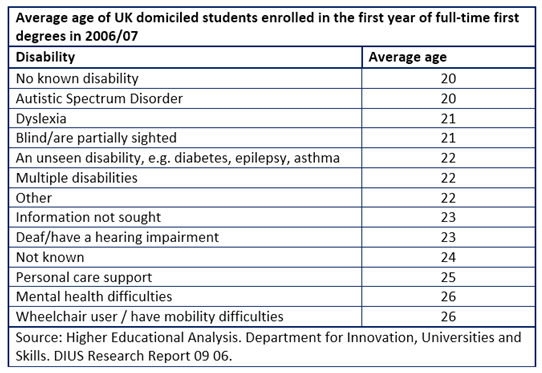

Other groups of students might have non-traditional qualifications or may have taken longer to complete qualifications than non-impaired students. According to HEA (2006[1]) the average age of UK domiciled students enrolled in the first year of full-time first degrees in 2006/07 was 20 for students with no known disability, but ranged from 21 for students with dyslexia and sight impairments to 26 for wheelchair users. For students who had declared a disability, only students with autism spectrum disorder had the same average age upon entry to university as non-impaired students. Delayed entry to university may be the result of receiving diagnoses comparatively late in their school career or having taken time out of education as a result of a period of ill health or for medical treatment.

Attendance

University and accrediting body rules, or T4 visa requirements, may mean we have little scope to determine attendance policy for a module or programme, but in cases where we can, or if we plan to have more stringent policies, we need to appreciate that students with impairments may have lower attendance levels than their non-impaired peers.

Students may have little choice in the dates and times of medical appointments or treatments such as physiotherapy or dialysis. Equally, some students will be unlikely to be able to predict when they are going to be sufficiently well to attend classes.

Students with several different impairments may find arriving at the correct location at the correct time for their taught sessions difficult. It might be difficult some students to arrive on time because of the route they need to take to avoid crowds or because of the time it takes to travel across campus as a result of mobility impairments.

Students with mobility impairments, including conditions that cause chronic pain or fatigue, may also face problems attending classes or events that take place away from the university campus or outside of normal teaching hours. If a student is eligible for personal care then they may have little flexibility in the hours their assistance workers are available, so scheduling visiting speakers, for example, in the evenings or weekends may mean that some students cannot attend.

If scheduling events off-campus or outside normal teaching hours is unavoidable, we could consider videoing the event, or allowing students to attend virtually via video conferencing. Alternatively, we could provide accessible transport for students to the event, or pay for a taxi for the student.

We should also consider how we approach recording absences. It can be deeply frustrating for a student to have to self-certify every absence if they have already notified the university that they have medical appointments at specific days and times.

Additional costs

It is very expensive to be disabled, not all treatments, assistive equipment and products are available free on the NHS. In addition, students who have mobility impairments are likely to incur higher transportation costs than their nondisabled peers and some students will need to follow strict diets which may be difficult to do on a budget.

Research done on behalf of the disability charity Scope in their report The Disability Price Tag 2019[2] attempted to estimate how much extra disabled individuals would have to pay to maintain the same standard of living as their nondisabled peers. They found that the average disabled person would have to pay an additional £583 a month, with one in five people with a disability paying more than an additional £1000 a month to maintain the same standard of living as an equivalent nondisabled person. These figures represent the extra that the individual would have to pay after taking into account any welfare payments designed to cover such costs. A similar study by the Extra Costs Commission in 2015[3] looking simply at the costs associated with disability found that individuals with disabilities needs to spend on average between £200 and £300 each week on goods and services directly as a consequence of their impairment. An example given in this report is of an individual with motor neuron disease who had to have an electric wheelchair made to measure. This costs £7,600 towards which individual had to pay £1,600 themselves. Both studies emphasise the additional utility bills incurred by people with limited mobility in order to keep warm and to recharge their wheelchairs, for example.

Another cost emphasised in both studies is that of transportation. Even when public transport is accessible an individual with a disability will still need to get to the station or bus stop, so they often rely heavily on taxis. This is a cost that will be incurred by people with a variety of impairments from those with limited mobility to those with agoraphobia or anxiety. These cost need to be considered in arranging any off-site or out of hours activities for students.

Students who don’t enter university via UCAS and international students are unlikely to receive the same financial aid as UK domiciled students will. It is therefore important that we try to avoid doing things that may cause students to incur additional costs if at all possible.

Field trips

See field trip section here.

Industrial placements

If an industrial placement is based in the UK then the host organisation is going to have similar legal responsibilities to disabled individuals as a university does.

There are however a number of questions we might want to ask ourselves about possible barriers that an industrial placement may have for students with impairments.

Questions we may need to consider

- Have accessibility assessments of potential placements taken place prior to the placement agreement?

- Is the industrial placement compulsory? If so, what are the consequences of non-attendance or non-completion due to ill health?

- What are the procedures for students undertaking placements who develop disabilities or temporary impairments during the placement, or become too ill to continue?

- Is there any flexibility in attendance and working hours for students with disabilities or temporary impairments?

- Do the students undertaking placements have the same rights as other full-time employees with regard to ‘reasonable adjustments’ and flexible working?

- Is it possible for students to return to study, instead of completing the placement? Equally, can a student defer undertaking a placement, if ill health prevents them from participating at the normal point in their degree?

- Most importantly, what are the procedures for equal opportunities monitoring to gauge whether students with disabilities are equally likely to apply for, and obtain, placements?

- We also need to consider how we would manage student interruptions and mitigation during the placement year.

The ‘with International Study’ Pathways/ study abroad

International institutions will be subject to different disability legislation than UK universities. Attitudes to, and provision for, students with disabilities can vary markedly by country as well.

Ideally we should find out about the accessibility of partner institutions prior to sending students there. We should also identify any possible barriers in advance so that students with impairments can make informed decisions about whether they will be able to succeed at that institution.

Question we may need to consider:

- What are the interruption and mitigation rules students will be subject to while they are at a partner institution?

- Is accessible accommodation available at the institution or in the locality? Is the institution accessible?

- Will the University’s insurer need to know details about a student’s health prior to travel, and if so, how we would to collect this information in an accurate and sensitive way?

- How do students access healthcare overseas? How do students register with a doctor and share their UK medical records?

- Are psychological services going to be available to students and, where relevant, will students be able to fully access them in a second language? Will students be able to access Exeter’s AccessAbility and Welfare services while overseas?

- Are there any restrictions on the medications that a students can take into a country, and will they be able to get prescription refills or equipment at the location overseas? For example, there are a number of countries which prohibit some of the medicines that we can obtain without a prescription in the UK such as codeine.

- If a student has dietary restrictions, for example as a result of kidney disease, will they be able to access appropriate food?

- Will care workers or support staff be available overseas?

- If a student is unable to continue their placement because of ill health what will be the consequences for their degree?

- Do we have a plan about what we will do in the case of a medical emergency? What is the protocol for informing the parents of a student or repatriating a student?

ILOs

There are, of course, some programmes and modules that by their very nature will be inaccessible to some students and are unlikely to attract students with particular characteristics. For example art, medical imaging and surveying programmes are unlikely to be accessible to students with significant visual impairments. However, we should not assume that particular impairments preclude students from taking and succeeding in particular field of study. There are numerous examples of people with disabilities succeeding in fields which might seem unlikely to the non-impaired.

Similarly, programmes that entitle students to begin work in a particular profession such as medicine or physiotherapy may necessarily exclude some students with significant impairments if they are unable to meet professional competency standards.

However, most programmes, will not be able to exclude students on the basis of their impairment. Students choose to take particular programmes for a number of reasons that do not necessarily relate to their future work aspirations, so we cannot exclude students based upon our belief that they wouldn’t succeed in a particular profession; a student may be taking a programme with a view to becoming a teacher, journalist or academic, rather than entering the profession itself.

When devising ILOs it is possible to inadvertently create barriers. For example, rather than saying that ‘students need to be able to assess visual images’, we could say that ‘students will need to evaluate a variety of media’ this would give the module lead the opportunity to be flexible in their assessment methods if a visually impaired student is in the class.

The purpose of ILOs is to make the module or programme objectives as clear as possible. Bear in mind that some students with specific learning disorders such as Autism Spectrum Disorder may take instructions and objectives very literally, and maybe unable to gauge implicit expectations.

Examples of ILOs that may inadvertently create barriers.

| Current ILO

Students must be able to: |

Barrier | Alternative ILO

Students must be able to: |

| Communicate orally and in writing. | BSL users may have limited speech. | Communicate through a variety of means. |

| Make concise, engaging and well-structured verbal presentations, arguments and explanations. | Oral presentations can be a barrier to students with speech impediments, BSL users and students with anxiety. | Make concise, engaging and well-structured verbal, filmed or written presentations, arguments and explanations. |

| Be competent in active listening and in leading, influencing and persuading others. | This excludes hearing impaired and Deaf students and may be difficult for students with Autism Spectrum Disorder. | Be competent in information collection and in making persuasive arguments. |

| Evaluate visual images. | This will be a barrier to visually impaired students. | Evaluate a variety of media. |

| Work with and relate to others. | This may be difficult for students with Autism Spectrum Disorder. | Collaborate with others. |

| Prepare clear detailed legible field notes, sketches, graphic sedimentary logs... | This may be difficult for students who do not have fine motor skills or who have visual impairments. | Prepare, or explain how to prepare, clear detailed legible field notes, sketches, graphic sedimentary logs... |

| Locate yourself accurately using a compass and base map, and develop the ability to "read" a base map to locate yourself. | This may be difficult for students with visual impairments. | Explain how you would locate yourself accurately using a compass and base map, and explain how to "read" a base map to locate yourself. |

| Visualise in three-dimensions. | This may be difficult for students with visual impairments or impossible for students who are congenitally blind. | Explain how one might visualise in three-dimensions. |

| Use a wide range of academic skills in data acquisition (through the use of equipment), interpretation (through calculation) and communication of results; | This may be difficult for students who do not have the fine motor skills or strength to use equipment and students with communication impairments. | Use a wide range of academic skills in data acquisition (through the use, or by directing the use, of equipment), interpretation (through calculation) and explanation of results; |

Learning activities and teaching methods.

For the most part, if you’re delivering teaching via the traditional pattern of lectures and tutorials or laboratories there are unlikely to be insurmountable barriers. Those that do exist will be highlighted in section Writing accessible teaching material and In-class adaptations, where we will discuss how to mitigate or eliminate such barriers.

Learning and teaching activities that do raise barriers to participation tend to be those where staff are trying to do something that is innovative and original. When devising a new program or module, the best way to make it accessible to as many students as possible is to build in flexibility. So you may wish to consider alternatives to the teaching and learning activities you propose, for cases when a student can’t participate in those activities.

As an example, you might choose to deliver learning experiences off-campus on Exmoor. Students value such activities, and they shouldn’t be discouraged, but we do need to think about how impaired students could participate. Such activities may cause barriers to students with mobility-based impairments and students with chronic pain or fatigue. So what could we do? There are variety of alternatives. We could consider videoing or live streaming the experience for the benefit of students who can’t attend. We could choose a route to take students that stays close to the roads so that an impaired student could drive, or be driven, the same route and meet us at agreed points. Could we consider alternative locations for the exercise?

At all times the onus is on staff to ensure that all activities are accessible.

Accessibility assessment/ audit

New programmes and modules must complete an AccessAbility report. An example, with guidance, can be found here.

References

[1] Department for Innovation, Universities and Skills

[2] https://www.scope.org.uk/campaigns/extra-costs/disability-price-tag/

[3] https://www.scope.org.uk/campaigns/extra-costs/extra-costs-commission/

Summary of the most common impairments

An introduction to the characteristics of the most common disabilities