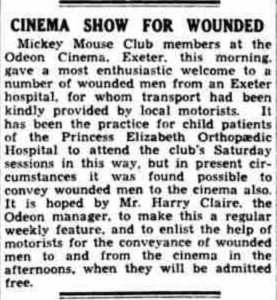

Cinema Show for Wounded is an article extracted from the Exeter newspaper, Express and Echo, published on the 15th June 1940. The newspaper published its first daily edition from 225/226 High Street in 1904. It is the result of a mix between the Western Echo and the Devon Evening Express, founded in 1864. The article talks about the famous Odeon cinema in Exeter opened in 1930, and the manager’s idea, Mr. Harry Claire, to convey wounded men from Princess Elizabeth Orthopaedic Hospital to the cinema regularly. He calls this The Mickey Mouse Club.

Every Saturday Morning, where do we go?

Getting into mischief? Oh dear, no!

To the Mickey Mouse Club with our badges on,

Every Saturday morning at the O-DE-ON!

Play the game, be honest, and everyday

Do our best at home, at school, at play;

Love King and country will always be our song,

Loyalty is taught us at the O-DE-ON!

The above is the Mickey Mouse Odeon Club song, which children sang before starting their weekly Saturday morning gathering at Odeon cinemas across cities in Britain, including Exeter. Being mentioned at the beginning of this extract, the club aroused our interest in its connection with cinema-going. The establishment of Mickey Mouse Club benefited the three parties tremendously, the cinema, Disney, and the nation. At a peak between 1938 to 1939, before the Second World War, the number of children joining the club surged from 150,00 to over 4.5 million. Thanks to this mass amount of youthful audience, the profits gained by the cinema and Disney could be massive. The purpose of the club expanded to educating children to be patriotic during the Second World War. As we can see in the extract, the club members, organised by the manager, provided free entertainment to the wounded soldiers. This arrangement not only helped to promote the cinema’s patriotic image but also encouraged children, who are a part of the home front and may be sent to the battlefield in the future, to serve the country in the ways they could.

The Odeon Cinema in Exeter, (opened in 1937) suffered bomb damage during the war that was not fully repaired until 1954. This was during the air raid in Exeter that took place on May 4th 1942. Despite this loss, the cinema was not closed off for an extended period of time and was re-opened in November to show films and other performances alike. In 1943, they brought back wounded soldiers to the mickey mouse club to watch screenings and performances with these footsoldiers to find comfort amongst the suffering. Some children would be reunited with family members. It’s fascinating that the cinema was re-opened only half a year after the bomb damage in Exeter, and that the pursuit of entertainment outweighed the paranoia of further air raids. This shows the efficiency of cinema as a morale boost to the people on the home-front and as a patriotic yet comforting experience during the war.

To conclude, this is evidence of the cinema being more than a simple film-centric experience. The movie theatre had multiple purposes; it was a theatre, a hall, a place for events such as the aforementioned Micky Mouse Club. A cinema was a place for social gatherings and emphasising and strengthening the patriotism that was vital for the country’s morale at this point in World War 2. The films themselves were simply an excuse much of the time for these communities to gather.

TUTOR COMMENTS

The attention to detail here speaks to a really strong understanding of key historical practice as a writer and a researcher: the group contextualize not just what the extract says, but the source that contains it, giving some contexts for the Devon-based papers before adding much specific detail, facts and figures about the activities the extract describes. The concluding lines are particular good in considering the way such sources provide evidence for rethinking how we approach cinema history – not just through films alone.