What kind of object/item is this?

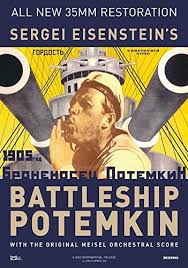

The chosen artefact is a leaflet from 1998 which advertises screenings of “Immortal Films That Shook the World”. The list included Sergei Eisenstein’s iconic picture Battleship Potemkin among other greatly impactful and influential films. This places it firmly among them as a significant piece of film history, even considered so in 1998, a startling 73 years since its initial release in 1925.

What can it tell us about Eisenstein and his place in film history?

The source tells us that Eisenstein is a very influential figure in film history, and his influence is still prevalent today. The film advertised in the source (Battleship Potemkin) is described as “immortal” and the leaflet claims that it “shook the world”. Eisenstein’s films were highly political. David Bordwell states that film history can help us “discover how creators and audiences responded to their moment in history”. Battleship Potemkin focusses on a public demonstration which resulted in a police massacre. Eisenstein’s films also “shook the world” in a cinematic sense because they made use of discontinuous editing and Soviet Montage. Despite the fact that continuity editing is the most common form of editing in mainstream cinema, this source tells us that Eisenstein’s unusual editing was clearly still influential and interesting to audiences in 1998.

What can it tell us more broadly about soviet cinema in this period?

The source can tell us that early soviet cinema is a masterpiece of politics, culture, and art. With the support of the soviet government, early soviet cinema is able to keep its originality apart from the western cinema. Soviet cinema creates coherence from different classes. In the film ‘Strike’, workers from young to old, male and female, were united against capitalism, creating a fruitful image of the ideology of communism. Also, people in the industry create the uniqueness of soviet cinema, from the movie “Man with the movie camera”, the editing skill of Dziga Vertox is cutting edge by the time and had expanded the possibility of editing from simple transaction to artistic way.

What can’t the source tell us?

Upon looking at the source, it can’t tell us the message behind the film. This is due to it only being a leaflet and therefore would have very limited information about the film itself. Although the leaflet states that Eisenstein’s film “shook the world”, it’s difficult to tell if this is meant in a positive or negative way, due to it being politically controversial, the reaction to the film would have been split. However, this source can’t tell us what demographic the film was targeted at and their reaction. It is clear that Eisenstein was influential with his film but it’s difficult to gauge just how influential by looking at only the source.

To conclude, in reading David Bordwell’s “Doing Film History”, he outlines 5 approaches to film history. This source would fit into his basic approach of cultural and political history as it focuses on the role of cinema in the larger society.

This is solid work that responds generally well to this week’s task. Your chosen source, a 1998 leaflet advertising films that shook the world is an original and thought-provoking one and you take time to showcase your clear knowledge of Eisenstein as a filmmaker as well as the contexts that shaped him.

Structurally, the piece responds to individual questions which is perfectly fine, but perhaps it could flow a little better. This is only a minor criticism as you write well generally, but I do think that framing the piece as an overall argument that incorporates the questions might be more effective still.

You draw on Bordwell to outline how the leaflet showcases cultural and political history which is good. However, there are still some questions about the leaflet that can be asked: where are these screenings taking place? Is it in a physical place or on a television station for instance? Knowing this can give us clues about the target audience. Taking a picture of the leaflet and including it would be helpful here.