After searching through the wide variety of Eisenstein-related objects and readings available in the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum’s archive, we chose to look at a press cutting entitled ‘Eisenstein’s Other Art: His Graphic Art’, listed on the catalogue online. That, however, is the sum total of the information available about it on said catalogue – therefore, we felt it necessary to visit the archive itself and physically examine the source.

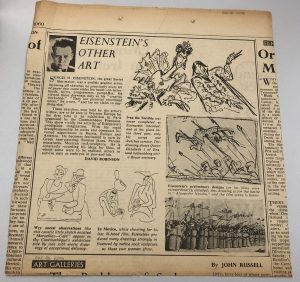

After closer inspection of the physical source, we deciphered that it is a press cutting from The Financial Times, written by the late film critic David Robinson in 1960, a celebrated journalist. It examines the correlations between Eisenstein’s sketches and his cinematic work.

Within the source, one of the key examples Robinson gives is a storyboard sketch of Eisenstein’s which heavily resembles the final battle scene in Alexander Nevsky (1938). He describes the art as “extraordinarily detailed”, as corroborated by a comparative still of the scene; this reflects Eisenstein’s directorial skill and meticulous attention to detail when recreating his visions in film form. Another source we looked at within the archive, alongside the press cutting, were images from an Eisenstein exhibition in 1989 where we noticed many of his sketches are of anthropomorphized animals completing mundane human tasks such as taking a shower, having a bath, in conversation or enjoying a massage. This reminded us of many instances in Strike (1925) where images of animals are similarly used in visual metaphors, taking the place of the bourgeoisie staff (and later the fleeing workers) at the factory – furthering the link between his sketches and his final films, and giving a greater sense of his directorial vision.

Robinson makes it clear that Eisenstein was as keen an artist on sketching paper as he was on celluloid; he writes “he is constantly recording his ideas for films, of which some were to be realised, others to survive only as embryos in pen-and-ink”. However, the source appears less useful in regard to the wider context of Soviet cinema, and even in regard to more acute aspects of Eisenstein’s own filmmaking, particularly his infamous and pioneering work in editing. Outside of introducing him as “the great Soviet filmmaker”, Robinson makes no reference in the short piece to anything wider than Eisenstein’s work, due to its specific topic. In terms of wider film history, by Bordwell’s categorisation, the article would only be truly useful in its assessment of “aesthetic history”, less so in regard to “biographical history”, and rather useless when approaching “industrial, technological or socio-political history”.

As with every source, critical thinking is always necessary; naturally, there are a few key questions to raise of Robinson’s article. As a respected film critic as well as a historian (even entrusted with writing Charlie Chaplin’s official biography), would we question Robinson’s reliability? What was the vested interest of the paper he was working for to publish this niche article 12 years after Eisenstein’s death? Similarly, it is important to examine any possible bias from Robinson; however, he writes with professional accuracy and there appears to be little evident bias that could change how we perceive Eisenstein. Contradictorily, it can be argued that there may be bias, in the sense that Robinson omits any criticism of Eisenstein.

A significant takeaway from this for us, though, is the importance of physically viewing the sources. Our chosen press cutting aided us far more in person than it could’ve done simply through the online catalogue, it gave us insight into an aspect of Eisenstein’s work we hadn’t previously encountered and therefore considered – that’s where artefacts like these in the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum shine.

This is tremendous work! The source you chose is highly interesting; I for one, have never come across it before, and it leaves me intrigued. I commend your initiative in going the extra mile and going to look at the source up close, for as you rightly point out, the library entry alone would grant us only limited information.

You mention yourselves how this was an important step and your point about seeing the artefact in material form being an entirely different (and more rewarding experience) is very well made.

You draw upon Bordwell to support your enquiry and importantly have taken time to consider the historian, in this case Robinson and his own place within film journalism at the time.

Great point about how the anthropomorphized animals in Eisenstein’s sketches can be linked to his depiction of the capitalist bosses in Strike. Also good images. Well done!