The source “Sergei M. Eisenstein: a biography” is a biography written by Marie Seton and can be found in the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum. This book provides an insight into the life (both personal and working) of Sergei Eisenstein and relates some key elements from the film industry during the Soviet period. As the first full scale biography of Eisenstein it allows a once naive film student to gain access to the context of Soviet Cinema and the influences that led to Eisenstein becoming the “Father of Montage”.

A source of this kind not only shows us Eisenstein’s background and approach, but can also tell us about the other filmmakers of the Soviet time period and their correlation to Eisenstein/contribution to Soviet Cinema as a whole. We can infer that this source tells us how the filmmakers of the Soviet Cinema period worked collaboratively and competitively to produce new, innovative and politically directed films that captured the attention of viewers around the globe. A key aspect of early Soviet Cinema was the use of montage created through collision editing, allowing two juxtaposing scenes to come together to generate a new belief/idea. An example of this in Eisenstein’s work would be the ending of Strike (1925) where the working class being brutally murdered is placed alongside graphic shots of a bull being slaughtered.

This source contains the biographical history approach as stated by David Bordwell in his essay “Doing Film History”, which contributes to explaining film history through a personal account of direct experiences that allowed Eisenstein’s work to become as renowned as it is today. Biographical sources such as this are useful in portraying a deeper level of intimate understanding that the films alone cannot provide, for example we can achieve a greater sense of his psychological thought process behind the ideas and draw conclusions on how his aesthetic and montage style came to be.

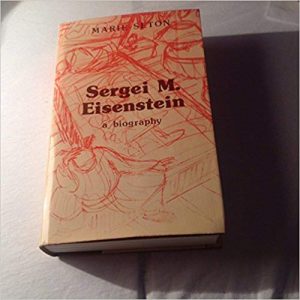

However, there are some things that this biographical source cannot tell us mainly due to the fact that it isn’t from Eisenstein’s own perspective but rather a collection of ideas presented in biographical format by another author. To overcome this you could also look at his memoirs in order to fill in the gaps a biography may have not covered; to look at one source alone provides a narrow insight into Eisenstein’s work, so using a range of sources from the Bill Douglas Cinema Museum is essential for any film analyst. The catalogue itself neglects to inform the inquirer as to the specific contents of the book and also lacks a cover page/image of the source (image above shows the cover, which we found online elsewhere) making it harder to locate physically in the Museum. By including a summary or brief extract from the source it would have allowed us to determine whether it would be suitable in providing the information necessary for the specific area of research.

Looking for this source first hand we would ask ourselves whether it would provide the depth and knowledge we require to achieve an overview of Soviet Cinema as a whole as well as Eisenstein’s work himself. It is also important to determine whether the source provides accurate information on the subject without bias or tampering, or any other form of corruption caused by history/politics.

This is impressive work that features a very well-chosen source in Marie Seton’s biography of Eisenstein. You write well throughout and your images (particularly the photo of the book in question) add to the effectiveness of the piece.

I like how you draw on Bordwell to outline both the effectiveness and limitations of a biographical approach to history and you make a very good point about supplementing readings of the biography with some of Eisenstein’s own writings (and he did write a lot). Question: are autobiographies objective or must we view them as just another perspective when studying a figure or film?

This is a very well-made point:

“We can infer that this source tells us how the filmmakers of the Soviet Cinema period worked collaboratively and competitively to produce new, innovative and politically directed films”

Sometimes in the rush to acclaim genius directors we can overlook how film is a collaborative medium that relies on a lot of people. This is certainly the case in Soviet cinema as you rightly point out.

Perhaps a little more information can be gleaned from the source. When was it published? Where? By whom? You will usually find this information online, but on the off chance that you don’t, it’ll be printed in the opening pages of the book itself.

Very good work overall.