Home » 2021

Yearly Archives: 2021

‘Darkness that might be felt’: A Black Woman in Imperial Russia

Black History is widely disputed; sometimes, even the most canonical narratives of Black lives are challenged and critiqued. The autobiographical Narrative of the great abolitionist campaigner Frederick Douglass has been contested by some historians for not going far enough in its condemnation of the American state for tolerating slavery; the life story of the poet (and freed slave) Phyllis Wheatley was appropriated and re-told by a white woman fifty years after Phyllis’ death. Yet other historically important Black life stories are not even read today, let alone critiqued. Nancy Prince, although less well-known today than Douglass or Wheatley, told her astonishing life story in her own words while opening a window onto St Petersburg, the capital of the Russian Empire in the nineteenth century. Her Narrative of the Life and Travels of Mrs Nancy Prince (1850) is still fresh and relevant today, as a page from Black history and as an unexpected view upon Russian history and culture. Extraordinarily, this uneducated Black woman from Massachusetts lived in Russia for nine years (and six months) between 1824 and 1833. She knew two Russian Tsars, or Emperors, and their wives personally. Later in life, after her husband’s death, Nancy travelled in Jamaica, then became a teacher in her native New England, finally writing her memoirs in order to share her inspiring experience and keep food on her table.

Almost two hundred years ago, Nancy Gardner Prince arrived in St Petersburg with her husband, Nero Prince. Nancy was born free in Newburyport, Massachusetts, in 1799, making her the same age as the poet Aleksandr Pushkin. Since her family was poor, she spent her young adulthood – after her stepfather’s death – doing menial work to support her mother and six younger siblings. Nero had been born in Marlborough, in England; he signed on with a merchant seaman and visited America and Russia several times. A Russian noblewoman hired him as a servant; later, he was given a role on the staff of the Tsar in St Petersburg. This was why Nero returned to the city in 1824, bringing Nancy. His new wife reported her first meeting with his employers at one of the Imperial palaces:

Almost two hundred years ago, Nancy Gardner Prince arrived in St Petersburg with her husband, Nero Prince. Nancy was born free in Newburyport, Massachusetts, in 1799, making her the same age as the poet Aleksandr Pushkin. Since her family was poor, she spent her young adulthood – after her stepfather’s death – doing menial work to support her mother and six younger siblings. Nero had been born in Marlborough, in England; he signed on with a merchant seaman and visited America and Russia several times. A Russian noblewoman hired him as a servant; later, he was given a role on the staff of the Tsar in St Petersburg. This was why Nero returned to the city in 1824, bringing Nancy. His new wife reported her first meeting with his employers at one of the Imperial palaces:

As we passed through the beautiful hall, a door was opened by two colored men in official dress. The Emperor Alexander stood on his throne, in his royal apparel. The throne is circular, elevated two steps from the floor, and covered with scarlet velvet, tasseled with gold; as I entered, the Emperor stepped forward with great politeness and condescension, and welcomed me, and asked several questions; he then accompanied us to the Empress Elizabeth; she stood in her dignity, and received me in the same manner the Emperor had. They presented me with a watch, &c.

Nancy notes: ‘there was no prejudice against color’. Later she describes Russian social conditions in the countryside: ‘The village houses are built of logs corked with oakum, where the peasants reside. This class of people till the land, most of them are slaves and are very degraded. The rich own the poor, but they are not suffered to separate families or sell them off the soil. All are subject to the Emperor, and no nobleman can leave without his permission’. It’s hard not to read comments such as these as implicit critiques of slavery back home in America, where families were routinely separated (like the infant Frederick Douglass from his mother) or sold on to distant farms.

Nancy’s stay in Russia was not all about critical race theory, however. She also gives us enthralling spectator portraits of two major historical events: the Decembrist rebellion of 1825, when a group of liberal Russian officers refused to accept the inauguration of the new Tsar, Nikolai I. In December 1825, they protested in Senate Square, St Petersburg, in favour of the Tsar’s brother, Konstantin; they also demanded a constitutional monarchy and an end to the practice of owning workers and peasants as ‘serfs’ (more soon on the difference between serfs and slaves). Their rebellion was firmly put down within a day, and the ringleaders and their families were executed or sent into Siberian exile. Nancy describes the excitement of that long December afternoon of insurrection, although she gets some details wrong (the Decembrists’ wives were not flogged, and no-one was burned on the scaffold). Even more vivid is her account of surviving the great St Petersburg flood of 1824, when the River Neva burst its banks, drowning an estimated 700 people, mostly in the poorer parts of the city where houses were flimsier (although the whole city was submerged as the waters rose by almost four metres). Most students of Russian learn about this flood when they read (in Russian or English) Aleksandr Pushkin’s famous 1833 poem The Bronze Horseman, in which his hero Evgenii survives by clinging to a stone lion (Evgenii’s fiancée is not so fortunate). Pushkin was not an eyewitness to the catastrophe, but Nancy was. Here is her story:

The morning of this day was fair; there was a high wind. Mr Prince went early to the palace, as it was his turn to serve; our children boarders were gone to school; our servant had gone of an errand. I heard a cry, and to my astonishment, when I looked out to see what was the matter, the waters covered the earth. I had not then learned the language, but I beckoned to the people to come in. The waters continued to rise until 10 o’clock, A.M. The waters were then within two inches of my window, when they ebbed and went out as fast as they had come in, leaving to our view a dreadful sight. The people who came into my house for their safety retired, and I was left alone. At four o’clock in the afternoon, there was darkness that might be felt, such as I had never experienced before. [At 10pm that day…] I then took a lantern, and started to go to a neighbor’s […]. I made my way through a long yard, over the bodies of men and beasts, and when opposite their gate I sunk; I made one grasp, and the earth gave away; I grasped again, and fortunately got hold of the leg of a horse, that had been drowned. I drew myself up, covered with mire, and made my way a little further, when I was knocked down by striking against a boat, that had been washed up and left by the retiring waters; and as I had lost my lantern, I was obliged to grope my way as I could, and feeling along the wall, I at last found the door that I aimed at. […The next day] I went to view the pit into which I had sunk. It was large enough to hold a dozen like myself, where the earth had caved in. Had not the horse been there, I should never again have seen the light of day, and no one would have known my fate. Thus through the providence of God, I escaped from the flood and the pit.

(The poet Pushkin was also Black; you can read more about his heritage here.) Although Nancy had developed a thriving business as a childminder and as a seamstress of high-quality baby linen (the TotsBots of her day, one might imagine – even Empress Aleksandra Federovna (left) ordered Nancy’s layettes for the little Grand Dukes and Duchesses), she couldn’t adjust to the cold, damp northern climate. She decided to leave St Petersburg and Russia for good in August 1833; by October, she was back in Boston. Her husband planned to remain another two years ‘to accumulate a little property […] but death took him away’. Nancy never married again or had children of her own, but her own extraordinary life and her social history of Russia and other nations keeps her memory alive. You can read more about her life here.

(The poet Pushkin was also Black; you can read more about his heritage here.) Although Nancy had developed a thriving business as a childminder and as a seamstress of high-quality baby linen (the TotsBots of her day, one might imagine – even Empress Aleksandra Federovna (left) ordered Nancy’s layettes for the little Grand Dukes and Duchesses), she couldn’t adjust to the cold, damp northern climate. She decided to leave St Petersburg and Russia for good in August 1833; by October, she was back in Boston. Her husband planned to remain another two years ‘to accumulate a little property […] but death took him away’. Nancy never married again or had children of her own, but her own extraordinary life and her social history of Russia and other nations keeps her memory alive. You can read more about her life here.

Arguably, Nancy oversimplified the similarity between Black slaves in America and Russian serfs. Their legal status was different: both were chattels (owned by other people), but serfs, unlike slaves, had legal status. They were responsible under the law for their own behaviour; they could (in some cases) sign contracts; and they even paid taxes.* Slavery was abolished in Russia under Tsar Peter I (the Great) in the 1720s, but at the same time serfs’ legal rights (including freedom of movement) became much more restricted. By the mid-nineteenth century, there were 22 million serfs in Russian – more than one-third of the population. (Compare the slave population of 3,953,762 in the US estimated by the 1860 census.) Tsar Aleksandr II finally abolished serfdom in 1861, but peasants continued to be economically disadvantaged (with heavy debts to their former owners) and some peasants were even (until 1907) legally obliged to remain on the farms where they had been born. Contrast President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, and the Thirteenth Amendment in 1865 which formally ended all slavery in America. As with Russia’s serfs, however, official and unofficial restrictions on the lives and legal rights of former slaves lingered on perniciously. Clearly, there was enough shared experience – and shared injustice – between American slaves and Russian serfs to make the Russian ruling classes uncomfortable, despite the lack of ‘prejudice against color’ that Nancy noted. America abolitionism was a political issue in the Russian Empire because the potential emancipation of one oppressed group would signal that the serfs, too, needed to be freed. This was, as John MacKay argues, probably why Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 novel Uncle Tom’s Cabin was so hotly discussed by Russian writers and intellectuals throughout that decade, and also why a Russian translation failed to appear until 1857 – much later than translations into other European languages (including Hungarian).** Like Nancy Prince, the Russian censors considered the parallels between slavery and serfdom to be too close for comfort.

In today’s Russia, a young female novelist called Evgeniia Nekrasova is writing a novel called Kozha (Skin). She is publishing the book in serial instalments, just as many nineteenth-century novelists, except that her book is appearing online – you have to subscribe to the BookMate platform to read her it. Nekrasova’s Skin tells the story of a young female Black slave, Hope, and a female serf called Domna, whose paths cross in nineteenth-century Russia. The two women discover that they can ‘exchange skins’ – to find out what that means, you’ll have to sign up to BookMate. As a white Russian woman, Nekrasova is aware that her novel might appear exploitative or ignorant; she insists, however, that ‘literature by Black women seems much closer to me, as a Russian-speaking female reader and writer, than 97% of all Russian literature’. According to Nekrasova, the collective female experience of oppression in patriarchal society gives her insight into the collective history of slavery – reading Toni Morrison’s Beloved inspired her to write about a Black slave. Nekrasova also studied Nancy Prince’s Narrative to inform Hope’s impressions of Tsarist Russia. Whether or not Nekrasova’s novel is successful, no doubt Nancy Prince would be happy that she is still inspiring Russians to think in creative, intersectional ways about Black history – and about their own…

publishing the book in serial instalments, just as many nineteenth-century novelists, except that her book is appearing online – you have to subscribe to the BookMate platform to read her it. Nekrasova’s Skin tells the story of a young female Black slave, Hope, and a female serf called Domna, whose paths cross in nineteenth-century Russia. The two women discover that they can ‘exchange skins’ – to find out what that means, you’ll have to sign up to BookMate. As a white Russian woman, Nekrasova is aware that her novel might appear exploitative or ignorant; she insists, however, that ‘literature by Black women seems much closer to me, as a Russian-speaking female reader and writer, than 97% of all Russian literature’. According to Nekrasova, the collective female experience of oppression in patriarchal society gives her insight into the collective history of slavery – reading Toni Morrison’s Beloved inspired her to write about a Black slave. Nekrasova also studied Nancy Prince’s Narrative to inform Hope’s impressions of Tsarist Russia. Whether or not Nekrasova’s novel is successful, no doubt Nancy Prince would be happy that she is still inspiring Russians to think in creative, intersectional ways about Black history – and about their own…

Dr. Muireann Maguire, Senior Lecturer in Russian

*For more on the differences between (and co-existence of) slavery and serfdom in Russia, see Ralph Hellie, ‘Slavery and Serfdom in Russia’, in A Companion to Russian History, ed. by Abbott Gleason (Blackwell, 2009), pp. 105-20.

**See John MacKay’s True Songs of Freedom: Uncle Tom’s Cabin in Russian Culture and Society (University of Wisconsin Press, 2013).

Students Re-Imagine Baudelaire: Through the Window and Into the Clouds

In September 2021, we welcomed returning final-year students back to their studies with a series of refresher classes after all the disruptions of 2020-21.

For one set of these classes, we set grammar books to one side and extended the great French poet Charles Baudelaire’s ‘Invitation to a Voyage’ to students. He claims that each one of us has an internal supply of natural opium to inspire and enthral us. In other words, the poet invites us to engage the limitless potential of our imaginations. Taking a leaf out of Baudelaire’s book, this particular class was to be an exercise in creative translation with an emphasis on the imagination.

Students looked briefly at one out of a pair of Baudelaire’s prose poems, namely ‘L’Étranger’ (‘The Stranger’ see English translation here) and ‘Les Fenêtres’ (‘Windows’, available in French and English translation here). They then had 15-20 minutes to produce their own version of it, by imagining their own encounter with a stranger in the clouds or by looking through a window in their mind onto a place of particular resonance for them.

The results are remarkable, a testimony to the innate creativity of our students who have already had to draw on their imaginations to think and be in another language. We also celebrate Baudelaire, who would have turned 200 in 2021, by extending his invitation to a voyage of the imagination.

Here’s the first set of poems based on ‘L’Étranger’:

In the clouds

- Are you alone here in the clouds?

- It is dark, it is raining.

- You are mysterious.

- I am not mysterious, I am afraid.

- You are afraid?

- Of light? Of darkness? Of joy? Of sadness?

- Of the world.

- But look down! The world is bright, the world is happy, the world is for everyone.

- So, why am I up here in the clouds?

Hannah Croutear

- So what’s your gimmick, then, Mr. Woke? Tell me about your family.

- I don’t have any worth speaking of, no parents or siblings.

- No friends then either?

- People come and go, for better or worse.

- And where do you come from?

- Many places, but what of them?

- And beauty?

- I see it everywhere, almost spiritually.

- Do you want riches? And fortune?

- Doesn’t seem to build a good lifestyle.

- So what do you even care for, since you have nothing left?

- Don’t you feel the breeze today? It’s so good to be here, wherever that is.

Afterthought:

Les richesses, et la fortune. Le sort. C’est quoi, sans les efforts pour les atteindre? C’est quoi, la vie, quand elle est remplie par les bêtises? C’est quoi, une maison, quand elle manque la porte? Et c’est quoi, une porte, quand elle attend toujours quelqu’un? Mur. Je vis, mais seulement quand les murs me permettent.

Mark Evans

En regardant les nuages rosâtres trébucher les uns sur les autres,

Je me demande serai-je jamais content ?

Le bonheur interne qui me manque devrait exister quelque part.

J’en suis sûr. J’en suis tellement sûr que ce néant me fait mal.

Les nuages quittent le ciel, révélant un azur aveuglant,

Avec son soleil fulgurant qui me brule les yeux

Et ses rayons qui embrassent ma peau,

Tout en déchirant mon corps en morceaux de l’intérieur.

Cependant, cette douleur me faire sentir à l’aise,

Elle me rappelle que je suis encore vivant

Soit à contrecœur, soit à dessein.

Jacob Farrington

-My body leaves me, floating in pure darkness. The silhouette asks, what is it like?

-It’s having no sensations, no responsibilities, no existence except from serenity.

-What was life like before? Says the silhouette

-Full of living, of existing, that world is still there but nowhere to be found.

-Is there fear?

-Not here

-Do you want to leave?

-Here I am a cloud, floating with no feeling, coming and going, sometimes existing, sometimes not.

Erica Harris

- Why is there only light?

- Because there is no darkness

- Where is the blue?

- There are only in orange and reds.

- What about words?

- There is nothing to say but to melt like the sun.

- And when does the sun rise?

- It only sets, moving towards the pink dusk.

Rhian Hutchings

Il se balade

Ses pas tombent avec soin

Sur le sol qu’il méprise

Plutôt, il préfère le ciel

Les nuages

Les autres, ils regardent leurs pas

Ses pensées sont à Terre

Mais il ne les connait pas

Il ne connait personne

Sauf ses amis nébuleux

Éphémères

Une fois rencontrés, ils disparaissent à jamais

Toujours différents, mais familiers tout de même

Cette amitié, c’est tout ce qu’il lui faut

Car le ciel le reflète

Toujours seul et jamais seul

Le ciel ne le quittera jamais.

Emily Maynard

He wanders

His feet tread carefully

Along the ground he ignores

Rather, he prefers the sky

The clouds

The others all stare at their feet

Their thoughts are of Earth

But he does not understand them

He does not understand anyone

Apart from his friends in the sky

Fleeting

Soon after meeting, they disappear forever

Always different, but familiar all the same

This friendship is all that he needs

Because the sky reflects him

Always alone and never alone

The sky will never leave him.

translated by Emily Maynard

Les Nuages

I’m watching the clouds,

They pass like time and life, across an ambiguous sky,

Will they darken and bring rain and life with them,

Or will they burn away and reveal the splendid sun above,

Revitalising, yet cruel.

The clouds intertwine, transforming into faces I once knew

And mesmerising patterns, drawing me further into my reverie…

A swallow soars upwards, undulating in the sky, headed towards the infinite universe above…

I wonder where she is she destined,

Is she returning home, to comfort and familiarity,

Or onwards, to new lands and uncertain skies,

To new ventures and risks,

Through turbulent tempests or over calm seas,

Skimming over waters of far-away lakes and oceans?

I will never know.

I wish her well with a nod of my head

And ponder what I’ll have for dinner…

Hannah Hall

And to conclude a pair of poems inspired by ‘Les Fenêtres’ (‘Windows’).

The sun bounces off the waves gently, casting a dim shadow in front of me as I look out over the sea. The small beacon of the lighthouse has lit up, a relic of safety from years gone by. We watch as the haze on the horizon creates murky skyscrapers, which rise from the sea as a lost city. Then, they pass, and we are left watching the container ships which have taken their place. Hundreds of goods transported from A to B. A floating island made of metal and oblivious to the numerous voyeurs on the shoreline.

A woman walks past on the beach with her dog, stopping only to pick up stones to throw for him. I wonder how far she has travelled to get here.

The window has a calming glow to it, a lulling sense of safety which beckons as if the warmth of the lowing sun is beating through it.

Isabelle Ferguson

The Window

I rise from my stupor, in the stuffy, shadowy room I call home in Exeter. I move lightly, guided by some deep yearning within me and open my window.

What awaits me is the most bright, bustling, and brilliant sight. My gaze settles on a waiter. His uniform pristine, his face set in a perfect, polite smile. He carries two overflowing flutes of deep golden liquid.

When he lays them on the ornate table bathed in perfect evening sunshine, my attention shifts to the women who grasp these glasses with fervour. Their skin is rosy, pricked by the strength of the sun’s rays.

The bustle softens, the music fades and what is left is the sound of their laughter. What beauty in that joyful noise? What envy to be as carefree as their shrieks of laughter sound?

I leave my room and join them, through my open window. The metal chair feels cool against my legs in this humid plaza in Northern Italy. Cold, bubbling, golden liquid glides into my mouth, leaving a trail of sticky warmth within me. I am boxed in by bold, boisterous buildings. Our table is pressed into a corner and yet I am the freest I’ve ever felt.

Sacha Warne

A Multilingual Celebration of Poetry

For the Festival of Discovery at the University of Exeter, staff and students from Modern Languages and Cultures gathered to share, translate and enjoy poetry in multiple languages.

A session on Colourful Language was a chance to reimagine a poem about language and colour in whatever language or idiom students chose. You can read the original poem, ‘Voyelles’ by the visionary French poet Arthur Rimbaud (written in 1871, when he was 16 years old), and a translation into English on Wikipedia.

A session on Colourful Language was a chance to reimagine a poem about language and colour in whatever language or idiom students chose. You can read the original poem, ‘Voyelles’ by the visionary French poet Arthur Rimbaud (written in 1871, when he was 16 years old), and a translation into English on Wikipedia.

Two students on the MA in Translation, Juliana Galán and Maria Florencia Fernández, have shared their versions with us. They translated the colours and images of the original into ones that speak of the landscapes of their Latin American homelands, demonstrating the diversity of Spanish across the continent.

Maria Florencia Fernández says: ‘I focused on the sounds and alliteration to convey what the vowels/colours mean to me, and I gave it a bit of Argentinian flavour with the pampas.’

A negro, E blanco, I rojo, U verde, O azul

Un día contaré qué hace cada vocal

A, enjambre negro de bichos que zumban

Amontonados alrededor de la podredumbre

Golfos en las sombras; E, candor vacío – nieblas y tiendas,

Flechas heladas del glaciar, reyes blancos, flores temblorosas;

I, púrpura, sangrienta, risas desde labios encendidos

De furia o penitencia ebria;

U, giros, vibraciones divinas de mares verdosos,

La paz de las pampas donde las aves revolotean, entrecejos que se suavizan

Cuando el alquimista cree haber logrado su premio

O, trompeta estridente suprema, silencio atravesado

Por mundos y ángeles que sobrevuelan – O,

lánguida letra perdida, omega, rayo alilado… Sus ojos…

Juliana Galán wrote ‘My translation does not take a literal approach. It does keep some of the same words and remains close to the text, but I mainly took the images and feelings that the author’s description evoked in me, social situations, politics, landscapes, nature, and my own memories. My translation is localized in Colombia and is driven by feelings and my heart.’

Vocales

A negro, E gris, I rojo, U azul, O dorado

Un día habré de hablarle a las vocales de su magia.

A, la muerte en traje de batalla, negra mortaja bañada en lágrimas saladas,

Las manos suplicantes de madres desesperadas

Playa al amanecer; E, candor gis – neblina y chinchorros,

Malocas y ciudades sagradas en las sierras altivas, hermanos sabios y gentiles, cardúmenes de peces sierra,

Alas que reposan en la ciénaga.

I, rojo, latidos y palpitaciones, mejillas delatoras, rostros del altiplano, labios expectantes,

El fin del día, el amor, la ira y la vida.

U, olas; vibraciones divinas de océanos infinitos

Media noche, profundidad insondable, vidas ocultas, bitácora de la humanidad

Cyan de cielos de verano, días de sol, burbujas etéreas.

O, celestial trompeta estridente, silencios atravesados de cuerpos fugaces

Aleteos de ángeles laboriosos,

O, la última letra olvidada, Omega; Helios, su rayo dorado

La divinidad, la luz, su alma.

You can listen to Juliana read her poem here.

A few days later we reconvened to share poems and songs in languages from Arabic to Welsh, including the indigenous languages of Mapuche and Quechua (click here to listen on Spotify).

While most of us shared works by other people, Laurine Collardeau shared a poem of her own in French. Laurine is a student of French literature at the Sorbonne who joined us from Paris as an Erasmus student.

Laurine says: ‘When I wrote ‘Empreientes’, I just had finished reading Proust’s A l’Ombre des jeunes filles en fleurs (1919), the second book of Proust’s novel A la Recherche du Temps perdu, which is about adolescent ego development, the first stages of love, memory, the experience of art… all at once. As I was reflecting on how memory works, I found it fascinating that people always leave something in us. This means that they don’t really leave a feeling but rather the remembrance of the time when the relationship took place. This is what the term ‘Empreintes’ (i.e. ‘footprints’) refers to. I like the idea that people leave footprints behind and that you are still able to follow them, yet footprints are sometimes misleading. Therefore, we tend to remember the best of someone and rarely the reasons why the relationship ended. This poem is a bit messy, which makes sense considering I’m stepping into adulthood and am right in the middle of figuring things out – if they can ever be figured. I write with what we call in France écriture inclusive which means I have not specified genders. This explains the use of a dot followed by an ‘e’ at the end of adjectives.’

Empreintes

Soudain comme un début in media res

J’ai vu ton visage au son du clocher

De la ville dont nous voulions nous échapper

Comment vas-tu ?

Qu’est devenu l’homme qui vendait des fruits au coin de ta rue ?

Le marchant de CD a déménagé

Son enseigne est un nouveau prêt-à-porter

Il faut construire pour enterrer le passé

Comment vas-tu ?

As-tu relu les notes que j’avais laissé dans tes revues ?

Si on avait su…

Je porte toujours les chaînes d’un bracelet aux paroles non tenues

Si mon adolescence n’est plus sur mon visage elle est sur le tien

Sur une silhouette qui me surprend à chaque fois que je la vois au loin

Sur un arrêt de bus qui me demande si je dois poursuivre mon chemin

Rien n’est fini

Si tout devient ruines

Tu es parti

Tes empreintes restent humides

Le futur faisait peur mais je t’y voyais

Sur des cartes aux distances déjà toutes tracées

Plains les trains fantômes de m’avoir éloigné.e

Que disais-tu ?

Te découvrir c’est comme être frappé pas un doux déjà-vu

Des tours de magie cèlent les amitiés

Je m’attendais à te voir t’évaporer

À entendre le silence quand j’ai décroché

Que dirais-tu?

En voyant que je lis encore les livres que je ne t’ai pas rendu

Si j’avais su…

Qu’aimer trop jeune c’est être incapable de vivre avec une vielle rancune

Si mon adolescence n’est plus dans mon langage elle est dans ta voix

Dans un nom qui hante l’aube de lettres qui n’ont pas survécu l’envoi

Dans des promesses qui reposaient sur l’interdiction des aux revoir

Et je suis sûr.e

Que tu les as tenues

Car les gentils voisins racontent que tu ne savais pas t’exprimer

Que l’on te reconnaissait mieux de dos à force d’avoir essayé

De fuir mais moi j’ai suivi des yeux les empreintes pour te retrouver

Je ne sais plus

Quand le soleil s’est levé

Mais d’autres sont venus

Et tes empreintes ont séché

Footprints, translated by Professor Hugh Roberts

Suddenly like a start in the middle

I saw your face at the sound of the bell tower

Of the town from which we wanted to escape

How are you?

What’s become of the man who sold fruit at the corner fruit of your street?

The CD shop has moved

Shop sign is for a new clothing store

You have to build to bury the past

How are you?

Have you reread the notes that I left in your magazines?

If we had known…

I still wear the links of a bracelet of unkept promises

If my teenage years aren’t seen on my face any longer they’re on yours

On the shape of your body that surprises me each time I see it from afar

When the bus stops and made me wonder if I must carry on my journey

Nothing is over

If all becomes ruins

You left

Your footsteps are still warm

The future was scary but I saw you in it

On maps on which distances were already marked out

Pity the ghost trains which took me away

What were you saying?

Finding you again is like getting hit not a sweet déjà-vu

Magic tricks hide friendships

I was waiting to see you vanish

To hear the silence when I hung up

What were you saying?

As I see I’m still reading the books I didn’t return to you

If I had known …

That loving too young is to be unable to go on living with an old grudge

If my teenage years are no longer in my langauge they’re in your voice

In a name which haunts the the dawn of letter that didn’t survive being sent

In promises which depended on forbidding farewells

And I’m sure

That you’ve kept them

For the nice neighbours say you didn’t know how to express yourself

That they recognized you better from behind by dint of your always trying

To flee but me, my eyes followed your footsteps to find you again

I no longer know

When the sun came up

But others have comes

And your footsteps have dried

If you have been inspired to write your own poem based on something you’ve read, please share it with us. Or just share your favourite poems and songs in any language in the comments.

‘The Invisible Troupe of Women’: Some Reflections on Historical Women’s Writing

By Dr Helena Taylor, Leverhulme Early Career Research Fellow in French. A post for International Women’s Day and Women’s History Month

When the novelist Marguerite Yourcenar became the first woman to be elected to the Académie française in 1980 she acknowledged in her acceptance speech the ‘invisible troupe of women who should have received this honour before [her]’ and whose ‘ghosts’ she would like to admit. As well as identifying several women writers by name — Mme de Staël, George Sand and Colette — Yourcenar also referred to ‘the women of the ancien régime [the 17th and 18th centuries], the queens of the salons who never dreamt of crossing this threshold; perhaps they feared that doing so would jeopardise their feminine sovereignty.’ (Discours de réception, Jan 1981).

By offering this acknowledgement, she gestures towards the (now well established) need to recover the works of women from the past who have been marginalised within or excluded from the canon: particularly those, who, as Yourcenar goes on to explain, were hugely influential and widely read at their time of writing. To some degree, this work of recovery has since been done for some of these salon women: Madame de Lafayette’s novel, La Princesse de Clèves, is studied for the French ‘Bac’ (A Level) and enjoyed an unintended boost in publicity in 2006 when the then President, Nicolas Sarkozy, questioned its relevance. Other writers of the seventeenth century, such as Madeleine de Scudéry or Madame de Villedieu, have gained attention within academic circles thanks to feminist scholarship, though a seventeenth-century woman writer is yet to make it onto the prestigious exam for the French teaching qualification, the ‘Agrégation’.

It is, however, the second part of what Yourcenar says which most interests me here: how did women writers establish authority in a patriarchal culture? Yourcenar suggests that some of these ‘queens of the salon’ did not seek to enter the all-male domain of the Académie française because to have done so would have threatened their authority, which capitalised on a particular construction of femininity. One of the women she is surely thinking of is the novelist, Madeleine de Scudéry (1607-1701). She hosted a cultural gathering in the reception rooms — the salon — of her house in the Marais in Paris. She was hugely influential as a writer: her works — some of which were co-authored with her brother and appeared under his name — were widely read and translated (into English, German, Italian, Spanish and Arabic). However, the closest she got to being recognised by the Académie française was to be offered a prize for her essay On Glory in 1671.

Taking place on Saturdays, her salon came to be known as the ‘samedis’. These gatherings attracted key philosophers, scientists, writers, and poets of the day. These were polymathic spaces where women of a certain class could, alongside men, read and discuss the latest literature, co-write poetry, probe questions of moral philosophy and debate new scientific discoveries. For instance, Scudéry engages directly with the topical question of the human/animal divide in a short observational essay about her exotic pets, The Story of Two Chameleons, a text we’ve been studying as part of the final-year module ‘Green Matters in Modern Languages and Cultures’. This was written in refutation of the philosopher René Descartes’s theory of the animal-machine and in dialogue with the more ‘scientific’ Anatomical Description of a Chameleon (1669) by Claude Perrault of the Royal Academy of Sciences.

The ‘feminine sovereignty’ came not only from Scudéry’s status as host, but also from the particular philosophy of gender and sociability espoused by the culture of her salon and present in much of her writing. Scudéry’s was not the only or the first female-led salon, but she was the author who reflected most strongly in her work – long novels ‘à clé’, as well as her philosophical dialogues, ‘conversations’ – the social knowledge of the salon world. In these works, she lambasts the restrictions of marriage, represents women in roles of authority and, significantly, reflects on what it means to be an intellectual in a patriarchal society. She advocates women’s education, and criticises constructions of gender that limited women to ornamental roles. Through the character of ‘Sapho’, a nickname amongst her friends and reference to the ancient Greek poetess, Scudéry calls women to overcome the restrictions of their gender: ‘Those who say that beauty is women’s part and that arts and letters and all the liberal and sublime sciences belong to men and that we have no part in them are equally far from both justice and truth.’ (Les Femmes Illustres [Illustrious Women] trans. Karen Newman, Chicago, 2003, p. 137).

However, she also emphasises difference rather than equality by delineating a feminised way of knowing on which her own authority relied, as Yourcenar suggests:

‘a woman may know languages, she may confess to having read Homer, Hesiod, and the excellent works of the illustrious Aristaeus without seeming a pedant; she can even offer her opinion in a modest way, without being aggressive, so that without transgressing what is appropriate for her sex, she can let it be known that she is a woman of wit, knowledge, and judgment.’ (L’Histoire de Sapho, 1654 [The Story of Sapho], Ibid. pp. 23-24).

In the opening of the Two Chameleons, Scudéry puts into practice this modesty: ‘I will not attempt to speak as a physician or as a philosopher, since I am not capable.’ (‘Histoire de Deux Caméléons’, Nouvelle Conversations de la Morale (Paris, 1688), pp. 496-542, my translation).

Her emphasis on difference, and her claims of modesty — however strategic — could be seen as a gesture of compromise, an unthreatening accommodation to male anxiety about women’s power that allowed men to justify women’s exclusions from other domains (such as the Académie française). But this emphasis could also be seen as the opposite, as a way of shifting our understanding of what knowledge looks like and what it meant to be ‘learned’, a proposition for intellectuals, male and female alike: her relationship with what Michèle le Dœuff calls ‘le sexe du savoir’ [‘the sex of knowing’] is therefore complex. Much of her reception has been more essentialising: she was mocked by some of her contemporaries and deemed a ‘précieuse’, that is, ridiculed for her pretensions to knowledge; and only relatively recently have critics begun to take her seriously as a thinker and philosopher as well as as a novelist.

Scudéry’s celebration of feminine traits was not the only approach women used to navigate the patriarchal world of literary culture. Marie de Gournay (1565-1645), some 40 years her senior, and first editor of Montaigne’s Essais, took a different line: she resisted feminised notions of modesty and argued fiercely for the equality of the sexes. Her dense, highly referential, wide-ranging essays demonstrate at every turn her learning, and her anger at her struggle as a woman to be accepted for it. In her key work of feminist theory, L’Égalité des hommes et des femmes (1626) [The Equality of Men and Women], she emphasised that there is no inherent difference between the male and female soul: ‘I am content to make [women] equal to men, given that nature, too, is as greatly opposed, in this respect, to superiority as to inferiority’. She adds: ‘the human animal, taken rightly, is neither man nor woman, the sexes having been made double not so as to constitute a difference in species, but for the sake of propagation alone (Apology for the Woman Writing, trans. Hillman and Quesnel, Chicago, 2003, p. 75, p. 86). Differences are socially constructed and need to be combatted: ‘It is not enough for certain persons to prefer the masculine to the feminine sex; they must also confine women, by an absolute and obligatory rule, to the distaff—yes, to the distaff alone’ (Ibid, p. 75). Her legacy is also marred by misogyny: interpretations of her work have been distracted by her body and its associated prejudices (there was a particular tendency to characterise her as a childless old woman with an unhealthy, pseudo-maternal affection for her cats), such that the full extent of her intellectual contribution is only beginning to be realised.

Equally, we might think of Anne Dacier (1647-1720), 30 years Scudéry’s junior, daughter of a famous scholar of Greek, Tanneguy le Fèvre, and the first woman to translate Homer. Her authority derived from her excelling in a world of knowledge usually gendered as male — Humanist erudition — and her production of learned translations from ancient Greek and Latin. She often used masculine forms of rhetoric, taking what Mary Beard describes as the ‘trouser suit’ approach: the ‘cultural template’ for a powerful person is male, so that adopting male-gendered attributes asserts authority (Women and Power: a Manifesto, London, 2017, pp. 53–4). For instance, Dacier would describe the men who disagreed with her methods of translating Homer in the very misogynous terms used against women: she compared her main opponent, Houdar de la Motte, to a ‘woman who knows little of the beauties of poetry’, likening his representation of the goddess Minerva to a ‘précieuse ridicule’ (Des Causes de la corruption du goût, Paris, 1716 [Of the Causes of the Corruption of Taste], p. 51, p. 477). Dacier’s authority meant that during her lifetime she wasn’t subject to quite the same gendered ridicule as Gournay and Scudéry, but she also fell prey to such criticism after her death: she was described, for instance, as ‘a harpie’ by Augustin-Simon Irailh (Querelles littéraires [Literary Quarrels] Paris, 1761, p. 311).

International Women’s Day 2021 — inclusive, intersectional, and global — shows how far feminist thought and action have progressed since the seventeenth century. Nevertheless, some of the same concerns persist: we are still required to negotiate patriarchal norms and, like the women discussed here, are confronted with different ways for doing so, from Sheryl Sandberg’s call to Lean In to Dawn Foster’s to Lean Out. We still encounter the gendering of knowledge (see for e.g. #ImmodestWomen), restrictions on girls’ education, the challenge of finding a voice and having it heard. As we focus today on pressing global concerns around silencing and invisibility, we might also pause for a moment to summon again the spectre of these ‘ghosts’ and others, invoking what they said — and did — in the context of the challenges still facing us today.

Reading Russian LGBTQ in Translation

By Muireann Maguire, Senior Lecturer in Russian and Principal Investigator for the ERC-funded RusTrans Project.

Russia and the nations of the former Soviet Union have a poor record in LGBTQ rights. In the former Soviet Republic of Georgia, for example, homosexuality was not de-criminalized until 2000 (although Georgia became an independent nation in 1991). And despite since passing anti-discrimination legislation designed to protect the rights of LGBTQ people, hate crimes are still difficult to prosecute; nor is transgender identity yet recognized under Georgian law. In a recently published essay, Natia Gvianishvili concluded that Georgia’s LGBTQ citizens are still represented in a highly politicized, primarily negative way (for example, portrayed as either deviants or victims).

In Russia, although male homosexuality was decriminalized twice in the twentieth century (in 1922 under Lenin, and by Boris Yeltsin in 1993), Russian society continues to be openly homophobic – an attitude encouraged by conservatives, including the powerful Russian Orthodox Church. President Vladimir Putin makes a flexible and politically convenient distinction between LGBTQ sexuality, for which he professes tolerance, and the dissemination of any information (including sex education) about alternative sexual identities, banned under Russia’s infamous 2013 ‘Gay Propaganda’ law. At its worst, such strategic collusion with homophobia condones serious human rights abuses, like the illegal detention and torture of gay men in the Russian Republic of Chechnya (ongoing since 2017), or the arrest in November 2019 of feminist blogger and artist Yuliia Tsvetkova. At its most ludicrous, last year an ice-cream manufacturer was accused of spreading queer propaganda by selling rainbow cones. The EU and OCSE have repeatedly censured Russia for allowing these abuses, to little effect.

Yet where politics can’t help, perhaps Modern Languages can. Put differently, while some Russian politicians may prefer not to acknowledge it, their country has a rich queer cultural heritage, widely studied and admired abroad. Russia’s Symbolist writers – Mikhail Kuzmin, Sofiia Parnok, and Lydiia Zinovieva-Annibal – were among the first twentieth-century Europeans to write openly about gay and lesbian love. And now, once again, the Russian LGBTQ community is enjoying a moment on the international stage – thanks to the translators, journalists, academics, independent publishers, bloggers, activists and ordinary readers who have helped to give genderqueer Russian writing a platform by translating and distributing it in the West. It’s been nine years since the post-punk dissident band Pussy Riot staged a protest performance in Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, calling for LGBT rights among other reforms. In the intervening decade, a number of more subtly challenging, equally dissident voices have gained a global following. The post-Soviet blog Punctured Lines recently drew attention to three important 2020 publications: Lida Yusupova’s poetry collection, The Scar We Know (Cicada Press); Galina Rymbu’s anthology of poems, Life in Space (Ugly Duckling Presse); and an edited collection of Russian LGBTQ writing, The Ф Letter: Russian Feminist Poetry.

Lida Yusupova is a lesbian poet whose radically uncontrolled prosody challenges aesthetic as well as gender assumptions (as in Yusupova’s ‘the centre for gender problems’, translated by Hilah Kohen); Galina Rymbu is a leading feminist author whose poetry (such as “My Vagina”) daringly interrogates preconceptions about the female body and female sexuality, and also the founder (in 2017) of the St Petersburg literary collective known as Ф-pis’mo, or F-letter, whose works appear for the first time in English translation in The Ф Letter.

In another important recent development, the February 2021 issue of the online translation journal Words Without Borders, “Russophonia”, is dedicated to showcasing new Russian writing, including an interview between the poets Galina Rymbu and Ilya Danishevsky. Danishevsky, known for his formally innovative poetic fictions Tenderness for the Dead (2014) and Mannelig in Chains (2018), says of contemporary poetry: “[it] has the ability to examine things in a maximally authentic way. This could be because it must continually reinvent itself and its language. […] And take, for instance, a discussion of love, a discussion in which it’s impossible to use dishonest words. […] In poetry, language about love is capable of expressing the very matter it describes.” As an editor (of Snob magazine), as well as a poet and novelist, Danishevsky is both a cultural mediator for Russian audiences and an original queer voice in his own right. Quoting one of Danishevsky’s translators Alex Karsavin, ‘Mannelig in Chains has been hailed by critics as a foundational text of queer modernism in the former Soviet Union, a movement that’s now coming of age. […] Written in the harsh afterglow of Russia’s 2013 “gay propaganda” ban, Mannelig portrays the queer subject as something more alienated than a confessor of illicit desire. The narrator’s accounts of trysts and personal tragedies function as entry points into collective traumas. […] The story occurs as a series of narrative threads (individual chapters) including erotic and platonic love; friendship; trust; childhood trauma; deaths of friends, siblings, and the dog; annexation (of both concrete geopolitical territories and abstract personal ones); and the commercialized, politicized deaths of Russian soldiers fighting in Ukraine. All this is overlaid onto a personal journey, which is itself tied to that archetypal journey narrative, the Odyssey. The book is, needless to say, a delightful challenge for the translators.’

Here at Exeter, within the Department of Modern Languages and Cultures, the ERC-funded RusTrans project is helping to bring Russian LGBTQ literature to Anglophone readers. The translation of Danishevsky’s novel, Mannelig in Chains, by co-translators Alex Karsavin and Anne O. Fisher, has been part-funded by one of twelve RusTrans bursaries seed-funding new translations of contemporary Russian literature. You can read the co-translators’ reflections on Danishevsky’s text here, and an extract from their version of Mannelig in Chains here. Perfect with rainbow ice-cream.

Recommended further reading: Connor Doak’s article ‘Queer Transnational Encounters in Russian Literature: Gender, Sexuality, and National Identity’, in Andy Byford, Connor Doak, and Stephen Hutchings, eds. Transnational Russian Studies (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2020), pp. 213-31.

If the shirt fits. Some thoughts on reading for LGBT+ History Month

Adam Watt, Head of Modern Languages & Cultures

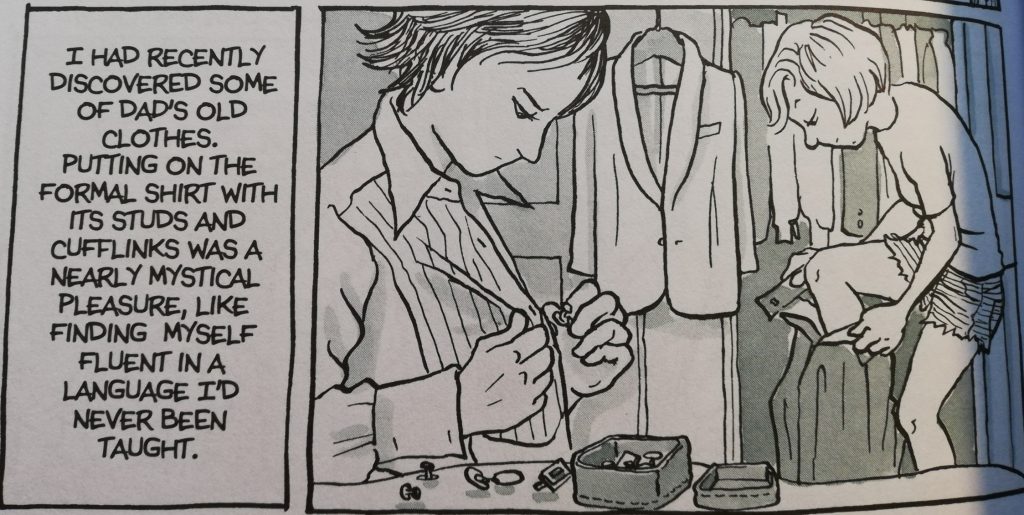

‘I had recently discovered some of dad’s old clothes. Putting on the formal shirt with its studs and cufflinks was a nearly mystical pleasure, like finding myself fluent in a language I’d never been taught.’

Alison Bechdel, Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic (Jonathan Cape, 2006), p. 182

Putting on someone else’s clothes brings a certain frisson: of intrigue, intimacy, comparison, transgression. In the lines quoted above, Alison Bechdel highlights the extraordinary transformative potential of something as ordinary as a shirt. Characteristically for Bechdel, her chosen image here is rooted in words that let us make up a world: the little girl pulling on her father’s shirt experiences something almost spiritual (‘a near mystical pleasure’), equivalent to being suddenly proficient in another language, but without the hard slog of learning it. In Bechdel’s two sentences we find a neat encapsulation of the theme for this year’s LGBT+ History Month: ‘Mind, Body and Spirit’. While some of us may have little truck with spirituality, or perhaps only very rare encounters with it, none of us can avoid entanglement in those other terms: mind and body. We are all, inescapably, embodied, carnal beings. Within and connected to our body is our brain. A sentient scaffolding of bone and muscle, ligament, tendon and all the other messy parts inside, holds up a hugely powerful data processing unit. We live, mostly, in the bodies we are born with: they age, mature, sometimes get modified or injured, carry children, give birth, are sites of pain as well as pleasure. One of the struggles of embodied life, as Katharina Volckmer has it in her recent novel about sex and gender identity, The Appointment, is that ‘the body others see is never the body we see’ (Fitzcarraldo, 2020, p. 58). Pulling on someone else’s shirt, however, covering and othering our body, can be liberating, invigorating, illuminating.

Bechdel’s image of mind and body here is intriguing since it intersects in a number of interesting ways with a moment in Proust’s A la recherche du temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time, 1913-1927), a novel that has an important place in the exploration of identity and sexuality we find in Fun Home (more on this below). In Le Côté de Guermantes, the third volume of Proust’s novel, his narrator reflects on the superficiality of the social world he now inhabits – one he long dreamt of, yet which transpires to be less inspiring than he had envisaged. He describes his ‘vie intérieure’ (inner life) as being dormant during a dinner party whilst the guests around him tell their boring stories. He qualifies this experience as:

ces heures mondaines où j’habitais mon épiderme, mes cheveux bien coiffés, mon plastron de chemise, c’est-à-dire où je ne pouvais rien éprouver de ce qui était pour moi, dans la vie, le plaisir. (A la recherche du temps perdu, ed. by Tadié et al, 4 vols, Gallimard 1987-89, II, p. 817)

those hours [during which] I lived on the surface, my hair well brushed, my shirt-front starched, in which, that is to say, I could feel nothing of what constituted for me the pleasure of life. (The Guermantes Way, trans. Scott Moncrieff/Kilmartin, rev. Enright, Vintage, 1996, p. 610)

Here the dress shirt, worn by its rightful owner, is a deadener of sensation, with its starched front (‘plastron’) a symbolic barrier to pleasure and the vital spark of the inner life. While the borrowed shirt offered a mystical pleasure and a new, queer fluency of connection between body and mind, the shirt worn as the conventional uniform of the worldly socialite shuts down any such possibility.

Bechdel’s book is a graphic novel about family and sexual identity. Fun Home is beautifully crafted, wickedly funny and often very moving. With the story of her narrator Alison’s father’s mostly hidden homosexuality and its impact on his life and family, Bechdel interweaves an account of Alison’s growing up and coming out as gay shortly after leaving home for college. After she comes out to her parents in a letter (it’s 1979), her mother reveals that her father has had affairs with other men. Shortly after, he dies in a road traffic accident that may or may not have been suicide. The book is an account of the narrator’s loss of her father, the process of her self-becoming and the ways in which her self-acceptance as a lesbian is intertwined with her father’s long denied sexual identity. The ‘fun home’ of the title is the family’s shorthand for the funeral home run by the father alongside his job as a high-school English teacher. As such, bodies—the dynamic, lively bodies of Alison and her family and the lifeless cadavers of the recently departed who arrive at the ‘fun home’ for pre-funeral preparation—pepper the panels and spreads of Bechdel’s book. Alison’s body develops and through it she starts to learn the confusing lessons of human sexuality. Spliced, like the strands of a rope, with these embodied discoveries are the explorations and encounters of the narrator’s queer, bookish and inquisitive mind. Bechdel repeatedly shows how we use the books we read to come to terms with who we are and to understand those around us. Much of Alison’s life experience—her joys and bewilderments and a good measure of her gradual unravelling of the mystery of her father’s enigmatic character and habits—comes filtered through reading and thinking about books that are read or encountered. There are brilliant reflections here on Henry James, Marcel Proust and Oscar Wilde, on James Joyce, Colette, Albert Camus and Kate Millett. Though Bechdel doesn’t say so, we might argue that reading literature (including Bechdel’s Fun Home, of course) is like pulling on someone else’s shirt. It allows us, after a fashion, to leave our body and our often troubled relation to it in order—in the safe and unregulated precincts of our mind—to explore the minds and bodies of others.

This may be one of the strongest arguments in favour of reading fiction: it gives readers access, of a sort, to the experiences of others. (Something argued eloquently in a recent book by my distinguished colleague Maria Scott – see here.) Whatever our sexual orientation, when we read Fun Home, or Alan Hollinghurst’s The Folding Star, or Douglas Stuart’s Shuggie Bain, or Colette’s Claudine novels they offer us that chance to immerse ourselves, after a fashion, in gay, queer or bi experience. In his recent memoir the novelist and critic Edmund White notes something similar. ‘Fiction’, he argues, is an ‘artform that places us in the mind of a perceiver. That is its great gift’ (The Unpunished Vice, Bloomsbury, 2018, p. 89). Access to the minds of others may well be fiction’s greatest gift and it’s one we should accept—and indeed seek out—with humility and openness. Reading texts ‘about’ or rooted in LGBT+ experience can change minds, inform minds, provide succour and solace, reassurance and resolve to body and spirit. If we want to enrich our lives and contribute to making our society a place of acceptance and understanding, even though it might not fit, it might feel awkward or unfamiliar, we need to put on that shirt.

Recent Comments