Reading Russian LGBTQ in Translation

By Muireann Maguire, Senior Lecturer in Russian and Principal Investigator for the ERC-funded RusTrans Project.

Russia and the nations of the former Soviet Union have a poor record in LGBTQ rights. In the former Soviet Republic of Georgia, for example, homosexuality was not de-criminalized until 2000 (although Georgia became an independent nation in 1991). And despite since passing anti-discrimination legislation designed to protect the rights of LGBTQ people, hate crimes are still difficult to prosecute; nor is transgender identity yet recognized under Georgian law. In a recently published essay, Natia Gvianishvili concluded that Georgia’s LGBTQ citizens are still represented in a highly politicized, primarily negative way (for example, portrayed as either deviants or victims).

In Russia, although male homosexuality was decriminalized twice in the twentieth century (in 1922 under Lenin, and by Boris Yeltsin in 1993), Russian society continues to be openly homophobic – an attitude encouraged by conservatives, including the powerful Russian Orthodox Church. President Vladimir Putin makes a flexible and politically convenient distinction between LGBTQ sexuality, for which he professes tolerance, and the dissemination of any information (including sex education) about alternative sexual identities, banned under Russia’s infamous 2013 ‘Gay Propaganda’ law. At its worst, such strategic collusion with homophobia condones serious human rights abuses, like the illegal detention and torture of gay men in the Russian Republic of Chechnya (ongoing since 2017), or the arrest in November 2019 of feminist blogger and artist Yuliia Tsvetkova. At its most ludicrous, last year an ice-cream manufacturer was accused of spreading queer propaganda by selling rainbow cones. The EU and OCSE have repeatedly censured Russia for allowing these abuses, to little effect.

Yet where politics can’t help, perhaps Modern Languages can. Put differently, while some Russian politicians may prefer not to acknowledge it, their country has a rich queer cultural heritage, widely studied and admired abroad. Russia’s Symbolist writers – Mikhail Kuzmin, Sofiia Parnok, and Lydiia Zinovieva-Annibal – were among the first twentieth-century Europeans to write openly about gay and lesbian love. And now, once again, the Russian LGBTQ community is enjoying a moment on the international stage – thanks to the translators, journalists, academics, independent publishers, bloggers, activists and ordinary readers who have helped to give genderqueer Russian writing a platform by translating and distributing it in the West. It’s been nine years since the post-punk dissident band Pussy Riot staged a protest performance in Moscow’s Cathedral of Christ the Saviour, calling for LGBT rights among other reforms. In the intervening decade, a number of more subtly challenging, equally dissident voices have gained a global following. The post-Soviet blog Punctured Lines recently drew attention to three important 2020 publications: Lida Yusupova’s poetry collection, The Scar We Know (Cicada Press); Galina Rymbu’s anthology of poems, Life in Space (Ugly Duckling Presse); and an edited collection of Russian LGBTQ writing, The Ф Letter: Russian Feminist Poetry.

Lida Yusupova is a lesbian poet whose radically uncontrolled prosody challenges aesthetic as well as gender assumptions (as in Yusupova’s ‘the centre for gender problems’, translated by Hilah Kohen); Galina Rymbu is a leading feminist author whose poetry (such as “My Vagina”) daringly interrogates preconceptions about the female body and female sexuality, and also the founder (in 2017) of the St Petersburg literary collective known as Ф-pis’mo, or F-letter, whose works appear for the first time in English translation in The Ф Letter.

In another important recent development, the February 2021 issue of the online translation journal Words Without Borders, “Russophonia”, is dedicated to showcasing new Russian writing, including an interview between the poets Galina Rymbu and Ilya Danishevsky. Danishevsky, known for his formally innovative poetic fictions Tenderness for the Dead (2014) and Mannelig in Chains (2018), says of contemporary poetry: “[it] has the ability to examine things in a maximally authentic way. This could be because it must continually reinvent itself and its language. […] And take, for instance, a discussion of love, a discussion in which it’s impossible to use dishonest words. […] In poetry, language about love is capable of expressing the very matter it describes.” As an editor (of Snob magazine), as well as a poet and novelist, Danishevsky is both a cultural mediator for Russian audiences and an original queer voice in his own right. Quoting one of Danishevsky’s translators Alex Karsavin, ‘Mannelig in Chains has been hailed by critics as a foundational text of queer modernism in the former Soviet Union, a movement that’s now coming of age. […] Written in the harsh afterglow of Russia’s 2013 “gay propaganda” ban, Mannelig portrays the queer subject as something more alienated than a confessor of illicit desire. The narrator’s accounts of trysts and personal tragedies function as entry points into collective traumas. […] The story occurs as a series of narrative threads (individual chapters) including erotic and platonic love; friendship; trust; childhood trauma; deaths of friends, siblings, and the dog; annexation (of both concrete geopolitical territories and abstract personal ones); and the commercialized, politicized deaths of Russian soldiers fighting in Ukraine. All this is overlaid onto a personal journey, which is itself tied to that archetypal journey narrative, the Odyssey. The book is, needless to say, a delightful challenge for the translators.’

Here at Exeter, within the Department of Modern Languages and Cultures, the ERC-funded RusTrans project is helping to bring Russian LGBTQ literature to Anglophone readers. The translation of Danishevsky’s novel, Mannelig in Chains, by co-translators Alex Karsavin and Anne O. Fisher, has been part-funded by one of twelve RusTrans bursaries seed-funding new translations of contemporary Russian literature. You can read the co-translators’ reflections on Danishevsky’s text here, and an extract from their version of Mannelig in Chains here. Perfect with rainbow ice-cream.

Recommended further reading: Connor Doak’s article ‘Queer Transnational Encounters in Russian Literature: Gender, Sexuality, and National Identity’, in Andy Byford, Connor Doak, and Stephen Hutchings, eds. Transnational Russian Studies (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2020), pp. 213-31.

If the shirt fits. Some thoughts on reading for LGBT+ History Month

Adam Watt, Head of Modern Languages & Cultures

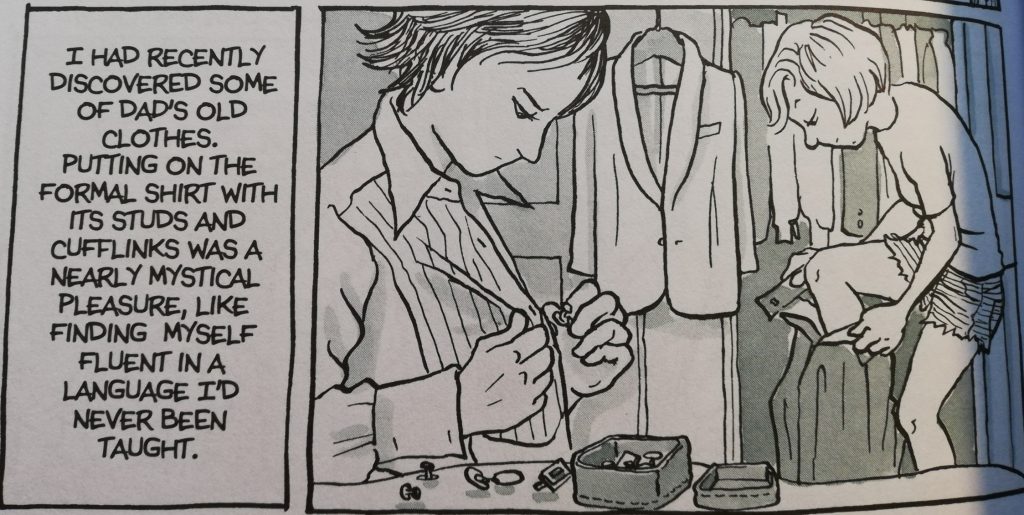

‘I had recently discovered some of dad’s old clothes. Putting on the formal shirt with its studs and cufflinks was a nearly mystical pleasure, like finding myself fluent in a language I’d never been taught.’

Alison Bechdel, Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic (Jonathan Cape, 2006), p. 182

Putting on someone else’s clothes brings a certain frisson: of intrigue, intimacy, comparison, transgression. In the lines quoted above, Alison Bechdel highlights the extraordinary transformative potential of something as ordinary as a shirt. Characteristically for Bechdel, her chosen image here is rooted in words that let us make up a world: the little girl pulling on her father’s shirt experiences something almost spiritual (‘a near mystical pleasure’), equivalent to being suddenly proficient in another language, but without the hard slog of learning it. In Bechdel’s two sentences we find a neat encapsulation of the theme for this year’s LGBT+ History Month: ‘Mind, Body and Spirit’. While some of us may have little truck with spirituality, or perhaps only very rare encounters with it, none of us can avoid entanglement in those other terms: mind and body. We are all, inescapably, embodied, carnal beings. Within and connected to our body is our brain. A sentient scaffolding of bone and muscle, ligament, tendon and all the other messy parts inside, holds up a hugely powerful data processing unit. We live, mostly, in the bodies we are born with: they age, mature, sometimes get modified or injured, carry children, give birth, are sites of pain as well as pleasure. One of the struggles of embodied life, as Katharina Volckmer has it in her recent novel about sex and gender identity, The Appointment, is that ‘the body others see is never the body we see’ (Fitzcarraldo, 2020, p. 58). Pulling on someone else’s shirt, however, covering and othering our body, can be liberating, invigorating, illuminating.

Bechdel’s image of mind and body here is intriguing since it intersects in a number of interesting ways with a moment in Proust’s A la recherche du temps perdu (In Search of Lost Time, 1913-1927), a novel that has an important place in the exploration of identity and sexuality we find in Fun Home (more on this below). In Le Côté de Guermantes, the third volume of Proust’s novel, his narrator reflects on the superficiality of the social world he now inhabits – one he long dreamt of, yet which transpires to be less inspiring than he had envisaged. He describes his ‘vie intérieure’ (inner life) as being dormant during a dinner party whilst the guests around him tell their boring stories. He qualifies this experience as:

ces heures mondaines où j’habitais mon épiderme, mes cheveux bien coiffés, mon plastron de chemise, c’est-à-dire où je ne pouvais rien éprouver de ce qui était pour moi, dans la vie, le plaisir. (A la recherche du temps perdu, ed. by Tadié et al, 4 vols, Gallimard 1987-89, II, p. 817)

those hours [during which] I lived on the surface, my hair well brushed, my shirt-front starched, in which, that is to say, I could feel nothing of what constituted for me the pleasure of life. (The Guermantes Way, trans. Scott Moncrieff/Kilmartin, rev. Enright, Vintage, 1996, p. 610)

Here the dress shirt, worn by its rightful owner, is a deadener of sensation, with its starched front (‘plastron’) a symbolic barrier to pleasure and the vital spark of the inner life. While the borrowed shirt offered a mystical pleasure and a new, queer fluency of connection between body and mind, the shirt worn as the conventional uniform of the worldly socialite shuts down any such possibility.

Bechdel’s book is a graphic novel about family and sexual identity. Fun Home is beautifully crafted, wickedly funny and often very moving. With the story of her narrator Alison’s father’s mostly hidden homosexuality and its impact on his life and family, Bechdel interweaves an account of Alison’s growing up and coming out as gay shortly after leaving home for college. After she comes out to her parents in a letter (it’s 1979), her mother reveals that her father has had affairs with other men. Shortly after, he dies in a road traffic accident that may or may not have been suicide. The book is an account of the narrator’s loss of her father, the process of her self-becoming and the ways in which her self-acceptance as a lesbian is intertwined with her father’s long denied sexual identity. The ‘fun home’ of the title is the family’s shorthand for the funeral home run by the father alongside his job as a high-school English teacher. As such, bodies—the dynamic, lively bodies of Alison and her family and the lifeless cadavers of the recently departed who arrive at the ‘fun home’ for pre-funeral preparation—pepper the panels and spreads of Bechdel’s book. Alison’s body develops and through it she starts to learn the confusing lessons of human sexuality. Spliced, like the strands of a rope, with these embodied discoveries are the explorations and encounters of the narrator’s queer, bookish and inquisitive mind. Bechdel repeatedly shows how we use the books we read to come to terms with who we are and to understand those around us. Much of Alison’s life experience—her joys and bewilderments and a good measure of her gradual unravelling of the mystery of her father’s enigmatic character and habits—comes filtered through reading and thinking about books that are read or encountered. There are brilliant reflections here on Henry James, Marcel Proust and Oscar Wilde, on James Joyce, Colette, Albert Camus and Kate Millett. Though Bechdel doesn’t say so, we might argue that reading literature (including Bechdel’s Fun Home, of course) is like pulling on someone else’s shirt. It allows us, after a fashion, to leave our body and our often troubled relation to it in order—in the safe and unregulated precincts of our mind—to explore the minds and bodies of others.

This may be one of the strongest arguments in favour of reading fiction: it gives readers access, of a sort, to the experiences of others. (Something argued eloquently in a recent book by my distinguished colleague Maria Scott – see here.) Whatever our sexual orientation, when we read Fun Home, or Alan Hollinghurst’s The Folding Star, or Douglas Stuart’s Shuggie Bain, or Colette’s Claudine novels they offer us that chance to immerse ourselves, after a fashion, in gay, queer or bi experience. In his recent memoir the novelist and critic Edmund White notes something similar. ‘Fiction’, he argues, is an ‘artform that places us in the mind of a perceiver. That is its great gift’ (The Unpunished Vice, Bloomsbury, 2018, p. 89). Access to the minds of others may well be fiction’s greatest gift and it’s one we should accept—and indeed seek out—with humility and openness. Reading texts ‘about’ or rooted in LGBT+ experience can change minds, inform minds, provide succour and solace, reassurance and resolve to body and spirit. If we want to enrich our lives and contribute to making our society a place of acceptance and understanding, even though it might not fit, it might feel awkward or unfamiliar, we need to put on that shirt.

Recent Comments