By Ioannis Lentas, Nikolaos Moustakidis and Bettina Derpanopoulou

Human Resources Directorate

Independent Authority for Public Revenue, Hellenic Republic

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a devastating impact on health and the economy across the globe. Governments have taken measures to control the spread of the virus and the consequences arising from this. These measures, include, for example, restriction of movement, social distancing, closed schools, and mandatory working from home. Though the production chain has been severely affected, governments have responded quickly by putting plans in place for ‘Remote Working’ (or ‘teleworking’). This blog discusses the results of a survey conducted by the Independent Authority for Public Revenue (IARP) of Greece via the Intra-European Organisation of Tax Administrations (IOTA) network. The objective of the survey was to better understand the challenges around ‘Remote Working’ in tax administrations and, importantly, identify the extent to which this mode of working can be sustained in the future. The survey was carried out during the summer of 2020 (through June-August) and it involved HR department managers from twenty two Tax Administrations [1]. The survey consisted of 13 closed questions.

With the risk of oversimplification the survey shows that respondents thought that:

- tax administrations have reacted quickly to introduce remote working,

- remote working, if managed well, can help in enhancing productivity but the impact on well-being needs to be understood and considered, and

- remote working cannot be applied horizontally across the organisations.

Figure 1: map of participating (in blue) countries

Main Findings

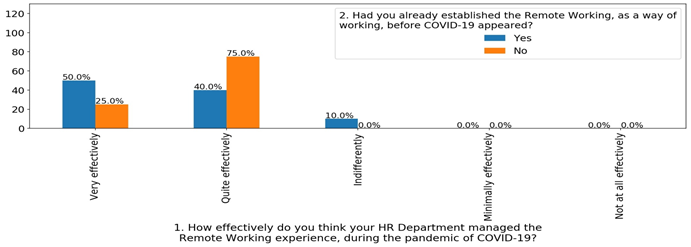

The majority of respondents (>95%) stated that their HR Department was effective in managing the remote working scheme during the COVID-19 pandemic, in spite of the fact that the majority (54.5%) had not previously established the practice before the start of the pandemic, in spite of the fact that the majority (54.5%) had not previously established the practice before the start of the pandemic.

Figure 2: Managing remote working

In addition, one third of the participants said that the organisation do not possess the technological equipment to effectively work away from their offices.

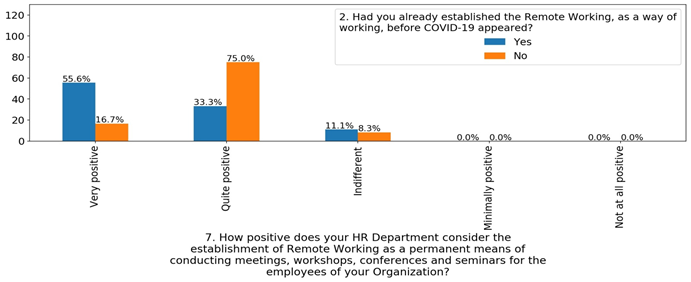

Interestingly, respondents (>90%) view the potential of remote working to conduct online meet-ups and seminars add real value to the organization.

The survey identified that respondents held different views on the frequency of ‘Remote Working’ and the needs associated with this, with most respondents preferring remote working for a specific number of days each week.

Remote working, however, is widely thought (80%) of being impossible to apply in a horizontal manner across all employee jobs and some differentiation would have to be made according to the tasks undertaken by the employees.

More specifically, the best fit for a remote working scheme was (in descending order): headquarter (70.6% selection rate), managerial, audit and lastly taxpayer service jobs (a mere 11.8% selection rate).

With regard to measures taken to help staff face the COVID-19 pandemic, tax authorities have responded quickly and provided information on contraction and spreading prevention measures. To a much limited extent, some organisations provided special care to vulnerable groups (45%) and 40% provided antiseptics.

A slim majority of respondents were also found to have conducted a survey to inquire staff members about their well-being (54.5%).

It was also reported by the vast majority of respondents (>90%) that their department (HR) was actively involved in the decision making process during the COVID-19 crisis.

Overall, a strong majority of over 85% of respondents appeared to be satisfied with the manner in which the crisis was handled by their organizations.

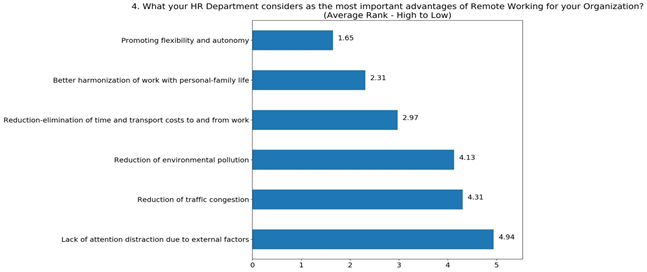

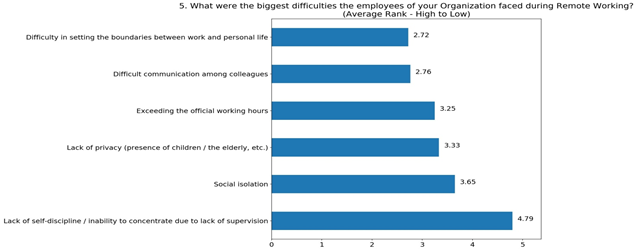

The top three recognised benefits of remote working comprise the flexibility and autonomy it offers, the improvement in professional-personal life balance and the elimination of transportation time and cost.

Figure 3: Advantages of remote working

On the flip side, the three most important difficulties in applying remote working were identified to be issues of setting boundaries between work and personal time, difficulty in communication among colleagues, and exceeding the official work hours.

Figure 4: Difficulties of remote working

Effect of established Remote Working implementation

We now explore how respondents with and without previously established implementation of remote working schemes answered the questionnaire in order to identify how this prior experience affects their responses.

Previous experience in remote working appears to correlate with more positive assessments of the COVID-19 response to implement remote working.

Figure 5: Overall effectiveness assessment vs. established remote working implementation

Established remote working schemes also correlate to a more positive view of remote working as a permanent means of conducting meeting activities.

Figure 6: Remote working as a permanent means of meeting vs. established remote working implementation

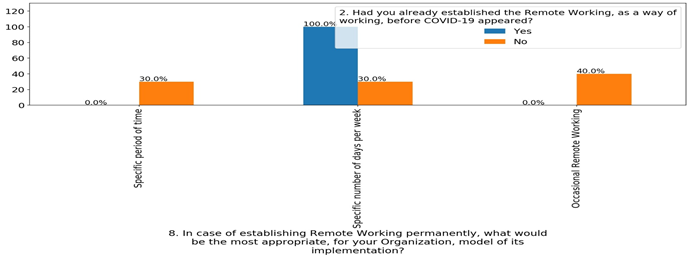

All respondents with established remote working agreed that a specific number of days per week is the more appropriate setup while those without were evenly split among the three options.

Figure 7: Remote working scheme selection vs. established remote working implementation

Those experienced with established remote working programs consider to a much higher degree (37.5% vs 8.3%) that remote working can be applicable to all jobs.

Another difference is the level of involvement that HR departments had in operational decisions during the COVID-19 pandemic. Organizations with established remote working were far more involved in the process (almost 90% reported ‘Fully’ participating) than those without (41.7% respectively).

Respondent Similarity – Clustering

Using the replies provided by the participating countries in the survey we can see how similar they are in their views and implementation on remote working and their response to the COVID-19 crisis.

Based on a similarity and clustering analysis three distinct clusters emerge:

Cluster No.1 comprising Belgium, Germany, Estonia, United Kingdom, Hungary, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia and Finland features excellent overall response satisfaction, previous experience with remote working, high HR involvement in decision making, significant means to apply remote working, and highly positive attitude towards remote working for use in meetings.

Cluster No.2 comprising Bulgaria, Latvia, Belarus, Moldova and Romania features the second best rates (after cluster No.1) in overall response satisfaction and in positive attitude towards remote working for use in meetings.

Cluster No.3 comprising Armenia, Greece, Spain, Malta, Norway, Russia and the Czech Republic features the second best rates (after cluster No.1) in previous experience in remote working, level of HR involvement in decision making and in means to apply remote working.

Conclusion

The survey showed that remote working, even in the occasions that was introduced for the first time, functioned quite effectively. It also showed that there are productivity gains from remote working but under the condition that it is designed correctly.

Therefore, it is of high importance to understand its challenges and take them seriously into consideration so that it can become more sustainable for the future, more efficient in terms of productivity and more appropriate for the well being of the employees.

[1] The countries which participated into the survey are: Armenia, Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Estonia, Finland, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Latvia, Malta, Moldavia, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Slovakia, Spain, United Kingdom.

Recent Comments