Today I’m kicking off a series of more reflective posts about women, translation, and the publishing industry: these will intersperse the review posts from time to time, to offer some context to the issues I’m researching and find interesting. I’ve also got some great guest writers lined up to contribute to this series, so I hope you’ll enjoy new perspectives on “Women Writing Women Translating Women”. I want to start the series by thinking about female voices getting lost in translation, and what we might do about this. A couple of things triggered this reflection, and I’m bringing them together here: the “Immodest Women” Twitter hashtag (and one particular response), the new Translating Feminisms kickstarter from Tilted Axis Press, and the Year of Publishing Women.

If you haven’t heard of the “Immodest Women” hashtag, it’s a rally for female academics to put their title in their Twitter name, because we worked hard for it and it is so often denigrated. I entirely support all those women who have done it, but I haven’t done it myself. Why? Well, you might argue that I am too conditioned to be a “modest woman”, but really I just don’t like using a title – any title. In the same way that I don’t want to be defined by my marital status, I also don’t want to be defined by my PhD. But I understand why so many women feel differently: I think we can all agree that the patriarchy is alive and well (there’s an excellent Guardian ‘long read’ by Charlotte Higgins on “the age of patriarchy” here), and that in most contexts, to paraphrase Ginger Rogers, women have to do everything men do, but backwards and in high heels. This is also true of getting published: books by women are priced lower than books written by men; of the much-quoted 3.5% figure (the percentage of UK sales accounted for by translated literature), less than a third is made up of writing by women; then there is the old “I don’t read women” chestnut.

Over the last weeks, I’ve read a lot of tweets from women sharing stories of how they have been belittled despite or because of their academic achievements, and I recognised myself in them all, but the one that really left an impression on me was a thread by feminist author Meena Kandasamy. She writes: “I am feeling extremely conflicted about the #ImmodestWoman hashtag and not because of self-righteousness but because there’s so much to unpack […] For every one of us who has managed to float up and breathe from that cesspool with a doctorate degree above our heads–we must remember our sisters sent home, their dreams crushed, their futures messed up, academia behaving like one petty thug-gang to have the backs of a few men.” Powerful words from a powerful woman, and an important reminder that however belittled we may sometimes (justifiably) feel, we still have that title, we still have a voice, we can still choose to be “immodest women”. So what really stood out for me in Kandasamy’s thread is the mention of people whose voices aren’t heard, the women whose dreams are crushed, and who may never get to be “immodest” because they simply don’t have a voice.

And voice is exactly where this coincides with writing, and translating. We can speak and be heard, even if the reaction is hateful (the “Immodest Women” debate made the top three headlines on the BBC news website in its first week, and there were some pretty unpleasant reactions to it), but many women cannot raise their voice, and if they did, who in the Anglophone world would hear it anyway? As Olga Castro wrote for The Conversation last year, “even those women authors who make the cut and become renowned writers in their home countries are not being translated for an English-speaking audience. There is a clear tendency to translate fewer women authors than men authors. Generalist publishers have been found to have obvious gender-biased attitudes when selecting titles for translation, and the work of women writers is far less often chosen for inclusion in translation anthologies.” There is an obvious issue here about lack of inclusivity, even with all the positive things that are being done to counteract gender inequality in the publishing industry, and though Castro was writing in 2017, this year’s “Year of Publishing Women” (more on that in a moment!) has not yet made the significant change we might have hoped it would.

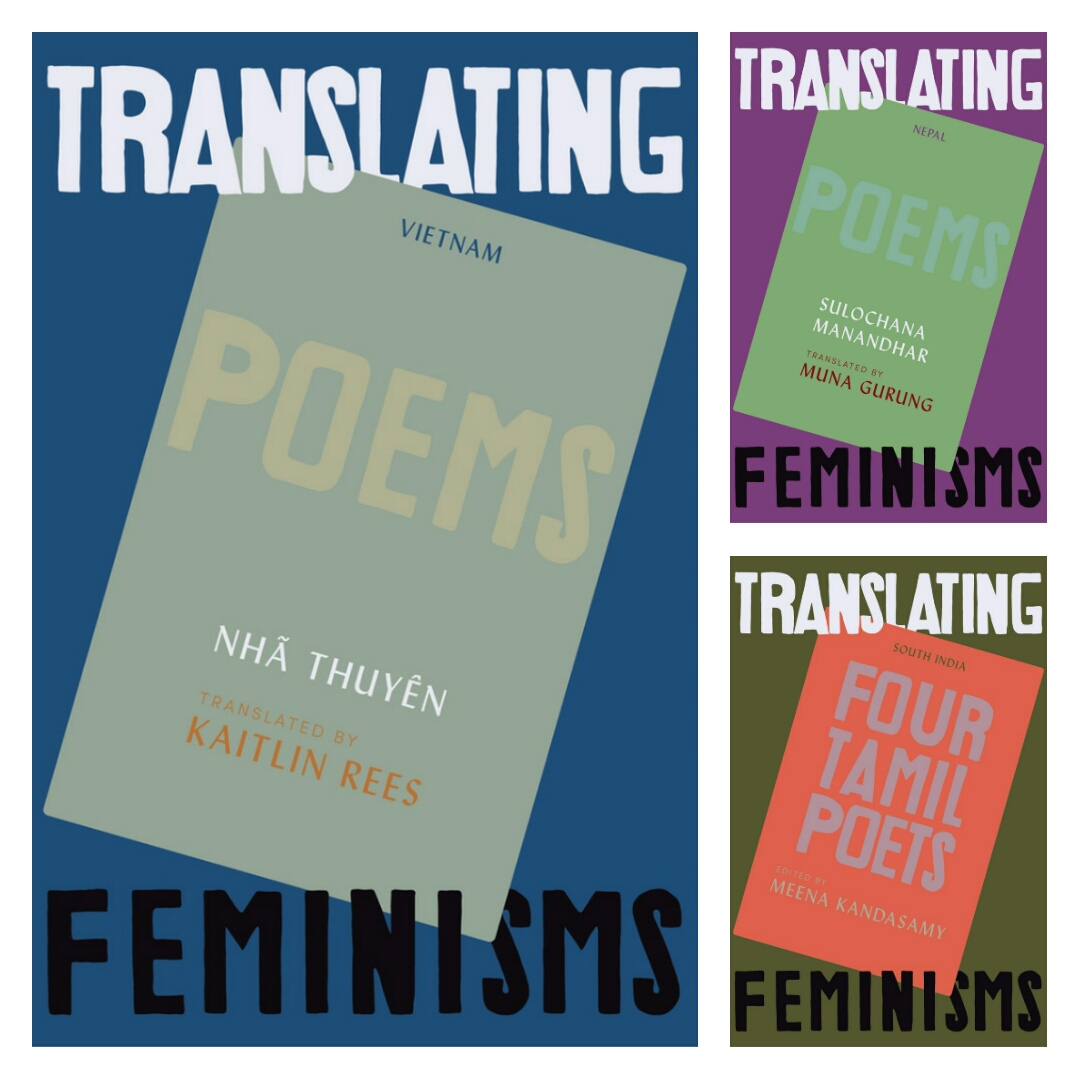

Tilted Axis Press are one of the pioneers doing something about this inequality: in a kickstarter-funded project challenging supporters to “smash the patriarchy”, they are proposing a series of chapbooks from women writers from Nepal, India and Vietnam. Tilted Axis already had excellent women-in-translation credentials: its founder, Deborah Smith, was the first recipient of the Man Booker International Prize (jointly with Han Kang; you can find my review of The Vegetarian here), and more than half of the authors and translators published by Tilted Axis are women. In particular, Tilted Axis focuses on literature originally written in languages that are not currently widely translated into English, and the Translating Feminisms project reinforces this, showcasing “intimate collaborations between some of Asia’s most exciting female writers and emerging-star translators: contemporary poetry of bodies, labour and language, alongside essays exploring questions such as ‘Does feminism translate?’” They situate this within a wider project of decolonisation through/ of translation, showing the importance of intersectionality in activism (here, specifically of feminism, decolonisation, and translation). This kind of project promotes dialogue between women across the world (and I can’t wait to find out how they answer the question “does feminism translate?”)

Tilted Axis have understood the importance of transnational feminism, and translation has an important role here: it is a powerful means to give voice to women who are doubly silenced – first, because they are women, and second, because they do not speak a dominant world language. Recently on the Vagabond Voices blog, I enjoyed a post about literary prizes and how these affect small independent presses. Part-way through this discussion, which is worth reading in its entirety if you feel so inclined, is this rallying cry: “coming into contact with foreign cultures helps you move beyond the borders of your reality. […] reading translations and stories told by unfamiliar voices is one way in which we can help bolster inclusivity and ensure that we are not closing ourselves off from Europe and the rest of the world. It is therefore important that continuous efforts are made to keep literary translation alive and growing.”

Though these comments are not specifically about translating women, they underline the importance of transnational dialogues. Translation is key to making “unfamiliar voices” heard, and inclusivity is equally crucial for making women’s voices heard; if the “Immodest Women” debate sprang from anything, I think it was lack of true inclusivity. But once we start to think about “inclusivity” we see it is far more wide-reaching than the academic context which was the springboard for the “Immodest Women” movement, and again it is the intersectionality that we need to be thinking about: how these voices raised in protest can join with those who struggle more to be heard. If “unfamiliar voices” can mean those from other parts of the world, it can also mean women’s voices. It’s not a huge step to alter the Vagabond Voices quotation a little and say: “coming into contact with WOMEN’S WRITING helps you move beyond the borders of your reality. […] reading translations and stories told by WOMEN is one way in which we can help bolster inclusivity […] It is therefore important that continuous efforts are made to keep WOMEN IN TRANSLATION alive and growing.”

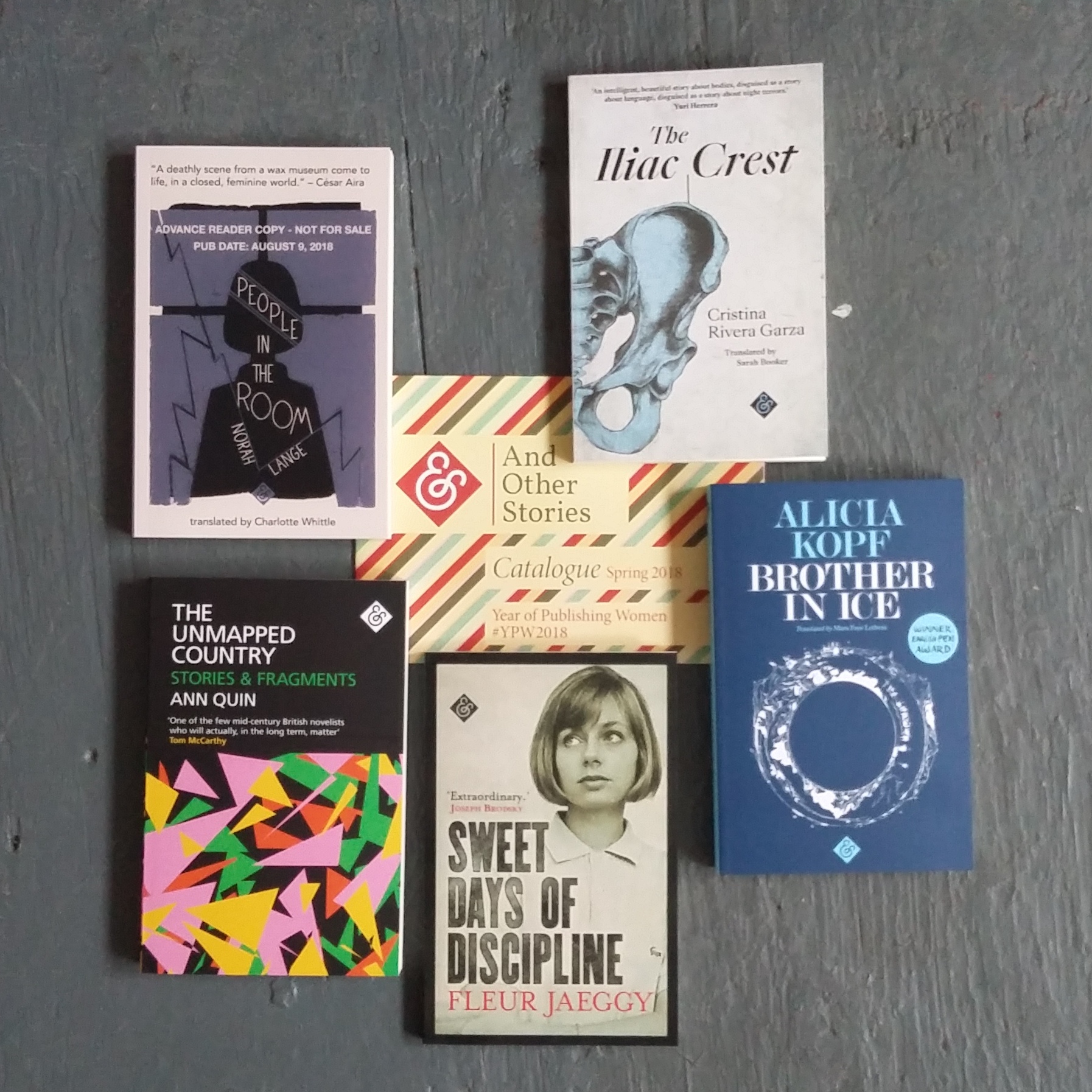

One publisher attempting to take on the lack of inclusivity and diversity this year is And Other Stories: back in 2015, Kamila Shamsie gave an impassioned speech at the Hay Festival, contending that books by and about women are unlikely to achieve the same kind of attention as those by and/or about men. As And Other Stories explains, “Even more incendiary than her argument […] was her proposed solution. In a provocation to all British publishers, big and small, she urged presses to highlight the problem, instigate discussion, and mark the centenary of female suffrage by publishing only women authors in 2018.” And Other Stories was the only press to take up the gauntlet. But if the recently released Brother in Ice (by Alicia Kopf, translated from the Catalan by Mara Faye Lethem) and People in the Room (Norah Lange, translated from the Spanish by Charlotte Whittle) are anything to go by, it was a gauntlet worth taking up. Kopf challenges the canon with her modern epic, and writes a book that is at once highly intimate and constantly outward-looking, while Whittle writes Lange’s twentieth-century Argentine classic of female lives into English for the first time with a translation that brings the original to life without seeming dated. I’ll soon be doing a full profile on And Other Stories and the Year of Publishing Women, so watch this space for more…

So what can we as readers do to promote women’s writing, and women in translation? Well, I’m a firm believer that small actions, multiplied, can make a big difference. If you buy books, try to buy them directly from the publishers where possible. If you can support these kickstarter initiatives, that’s a great way to make a difference. If not, don’t underestimate the power of your voice. If you liked a book by a woman author, tell people. As many people as you can. Whether it’s a blog like this or a tweet or a book club or a chat with your friends, spread the word. One of my favourite comments about inclusivity (and the one I’m constantly repeating) is from Erin Dexter, who a couple of years ago said in a BBC news feature that “Feminism is for everybody, because sexism damages everyone. If you’re not a feminist you’re either a misogynist or you need to look in a dictionary.” Feminism is about all of us working for change, whether it’s in the books we read, the organisations we support, the voices we promote, or the prejudices we reject. As Kandasamy reminds us, “Individual success is great, but collective change is urgent.” We all need feminism, and we all need to extend our concept of what this is, so that all women’s voices are represented – in literature as well as in society.