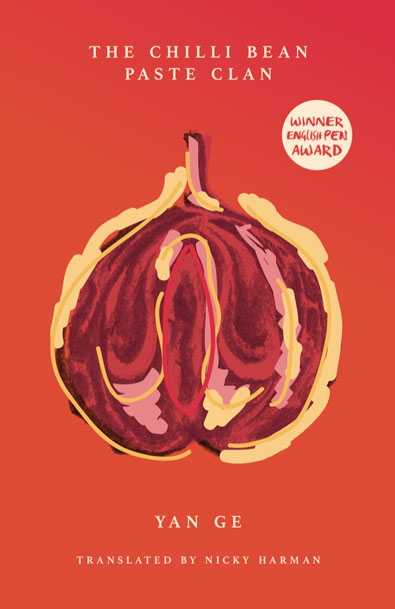

Translated from the Chinese by Nicky Harman (Balestier Press, 2018)

This is the first of a double feature on the Translating Women blog: today I’m reviewing The Chilli Bean Paste Clan, published by Balestier Press, and next week I’ll be bringing you an exclusive interview between author Yan Ge and translator Nicky Harman.

Set in a provincial village in China, The Chilli Bean Paste Clan is the tale of a family empire with the formidable Madame May at its head. As May’s 80th birthday approaches, her middle-aged children gather to prepare an unforgettable celebration, but find themselves caught up in old rivalries and new problems of the heart.

Meet Dad, the unlikely anti-hero of the story, and heir apparent to the family business, the Mayflower Chilli Bean Paste Factory. He has been working there since he was a teenager, initiated in the ways of stirring vats of fragrant bean paste by the grouchy shifu Chen. Dad’s older brother went off to university and never returned to the village, making a living now as an academic. His sister married a rather useless man, and Dad himself made a happy enough marriage, but that is not enough to keep him from having affairs because, after all, “a man always needed girls to screw.” When we meet Dad, he is embroiled with an artful young mistress named Jasmine. He has installed Jasmine in an apartment just above Gran’s (Gran is the aforementioned matriarch, Madame May, a woman “no one in this family has ever got the better of”), and you can imagine the misadventures that ensue with Dad’s much-feared and revered mother living on one floor and his pert-bottomed mistress just above.

Dad is an unremitting misogynist, for whom women are shrews, vixens, or turtledoves, whereas men – oh, heroic, misunderstood men! – are like the mighty Yangtse River. They are maligned and vilified, their urgent sexual needs not understood, their contribution to society absolute. His character is perhaps best summed up in this section, which combines both his sexual indiscretions and his world view:

“Dad gave her a couple of savage thrusts. He felt extremely aggrieved. It was hard just being human, let alone being a man. It was ever thus. He was one of the workhorses of this life, always needing to do the hard graft. He was fated to be the doormat, working himself to the bone to satisfy his mistress, and so give his old mother a good night’s sleep. Saints and sages were always lonely and misunderstood, always put upon, always working.”

Poor fellow.

And things only get worse for Dad when his lives and lies start to close in on one another after he faints mid-passion in Jasmine’s apartment. An inclination towards both sexual and gastronomical excess is taking its toll on his heart, and he ends up centre stage in a hospital bed, with the women in his life tending to him. Even though both his wife and his mistress are catering to his every need, he is still overcome with self-pity; he’s an unlikeable character alright, but one of this novel’s great achievements is to make you want to know what happens to him even though he is so repellent that you surely wouldn’t have minded too dearly if the heart attack he had in the throes of his passion with Jasmine had been fatal.

The main characters are all brilliantly developed: the brother who left the family and the village behind and is Dad’s main source of resentment has private sorrows of his own, and the moment when the two men realise that all their life they thought the other had everything while they were hard-done-by in comparison is achingly beautiful. At the centre of this revelation – though not present for it – is Gran, who loved her children by trying to make them respectable according to what she perceived as their own particular talents. So blinded by her own experience of being looked down on, she put the family reputation before the happiness of her children, thinking the latter would follow from the former. Gran’s misjudgement is heartbreaking not only because of the wasted years of her children, but also because of the sacrifice we learn she made herself in order to “keep up appearances”.

If the main character is Dad, and his mother is Gran, then you might wonder with good reason who the narrator, Xingxing, is, for she is never present at any of the scenes that she narrates. In fact, we learn very little about Xingxing apart from one vital revelation: she spends the entire period of the narrative in a psychiatric asylum. I was expecting there to be some explanation for how she came to be there, and for her character to be developed alongside the others, but there is no such disclosure. At first I was a little taken aback by this, and then realised that this is part of the originality of the novel: we think all the family secrets are being revealed to us, but they are not. If you should wonder how Xingxing manages to know so much about the family affairs and events that happened in her absence or before her birth, she tells us subtly yet repeatedly: comments such as “That son-of-a-bitch Zhong broke down. Tears poured down his face, Dad told me”, “Later she told me: ‘But this time he’d gone too far. It was a matter of principle’”, and “That may have been Dad’s view, but Mum had another take on it” reveal how Xingxing came to know so much, and at times she even deliberately reports on the extensive investigation she undertook to compile the family history: “To properly get to the bottom of all this, I needed to ask every one of the people involved, without missing anyone out.”

The relationships are what this book is built on: the squabbles between the middle-aged siblings, the rampant misogyny of Dad and his gang of boozing buddies, and the tensions between spouses and lovers are superb, with the dialogues being particularly well translated. Indeed, the colourful language in The Chilli Bean Paste Clan is one of the things that makes it so distinctive and so enjoyable. Harman conveys some of the linguistic idiosyncrasies of the Chinese (when Dad’s driver curses pedestrians, we are told that he “stuck his head out of the car window and shouted lengthy picturesque references to their ancestors”), as well as allowing some of its proverbs and sayings to come through in the English (I especially liked “you can’t fill a belly without belching”).

In amongst the comings and goings of the clan, we find comments on both history and modernity: Dad reflects on the overcrowded town that “everyone had more cash to spend and nothing to spend it on. They lived in this piddling little town, where walking from East Street to West Street only took fifteen minutes, yet every family insisted on getting a car, then spent their time weaving in and out of traffic jams in the clogged-up streets,” and Madame May opines that “The younger generation really had no idea how devastating it had been, decades ago, when she took her old father’s arm and led him out of the gates.” This is a family saga rooted in its place and time, and if the narrator is distanced from it all, then perhaps this reflects Yan’s own need, described in the foreword, to “move to the other side of the world to write about my hometown.”

This is a rollicking, engaging saga of a story: I enjoyed it from cover to cover, and I thoroughly recommend it. Come back next week to find out how Madame May and the Mayflower Chilli Bean Paste factory got their names, why The Chilli Bean Paste Clan was born out of Yan Ge’s anger, and how Nicky Harman translated a rhyming couplet imbued with classical allusions that reveals the biggest of all the family secrets to the reader, but not to the characters. You won’t want to miss this one!

Review copy of The Chilli Bean Paste Clan provided by Balestier Press