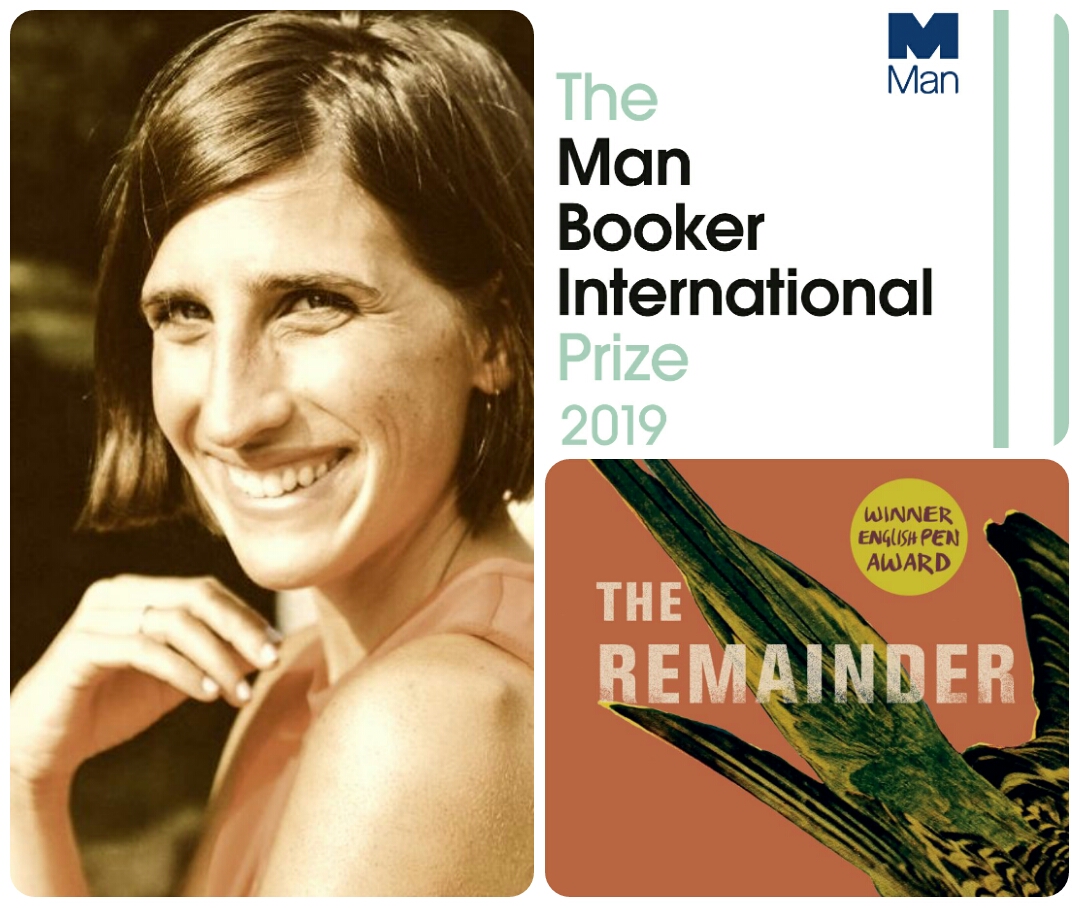

I’m delighted today to bring you an interview with Sophie Hughes. Sophie is the translator of Alia Trabucco Zerán’s The Remainder, which was published by And Other Stories as part of their commitment to the Year of Publishing Women, and is currently on the shortlist for the 2019 Man Booker International prize. Sophie has also translated novels by Spanish and Latin American writers such as José Revueltas, Enrique Vila-Matas, Rodrigo Hasbún and Laia Jufresa. She has been the recipient of a PEN/Heim Translation Fund Grant and six English PEN translate awards, and is a translator I greatly admire: the MBI shortlisting is testament not only to an excellent novel by Alia Trabucco Zerán and to the positive changes that And Other Stories have set in motion with their commitment to the Year of Publishing Women, but also to Sophie’s great passion for and investment in her translations, and to the immense skill with which she carries them out.

Helen Vassallo: How did you first come across The Remainder? Did you pitch for it, or was it offered to you?

Sophie Hughes: The writer and my friend Carlos Fonseca wrote to me saying he thought I’d like his friend’s debut novel. He knew I was translating a cult Mexican novella called El apando (The Hole, by José Revueltas, published by New Directions and co-translated with Amanda Hopkinson), which has a strangely hypnotic but relentless prose style. The first page of that novella unfolds in a single sentence; one half of The Remainder is written as a single sentence… Carlos clearly thought I hadn’t set myself enough of a challenge! So I was just lucky enough to read the book early. I then applied for a PEN/Heim Translation Grant and got it, and that paid for me to work on translating the whole novel. In the meantime, Alia got a world-class agent, and I think Stefan at And Other Stories read a sample on PEN’s dedicated webpage for the PEN/Heim grant. He was bowled over by Alia, as I had been, and asked me to do the translation. I actually pushed back my maternity leave to finish it, which is mad, of course, but love is mad, and I loved the book.

HV: What was it about The Remainder that you found particularly engaging, and that you think readers and the MBI judging panel have enjoyed in it?

SH: It’s impossible to say why the judges or other readers enjoyed it – I’m just pleased they did. I fell for Felipe, one of the novel’s three young characters living in the shadow of the Chilean dictatorship and who take a madcap road trip in a hearse to retrieve the body of one of their ex-militant mothers. Felipe is a rambler, a serial overthinker, an accidental virtuoso spewing his past and present out in one long sentence – it’s not always easy to read, actually, and can feel quite exhausting with all the constant digressions, but it was fun to translate! It meant I could throw out the grammar rulebook and just listen and try to improvise consonant cadences in the English (we look for close approximations all the time as literary translators, but more obviously so with semantics: jokes and sayings, etc.). More so than with other books I’ve translated, this was an exercise in close listening: translation as an infinite canon. One annoying detail when translating the book was the Spanish noun “el muerto” – “the dead man/person” – which comes up all the time. In the plural it’s easy – if inescapably Joycean – “the dead”, but “the dead man” is a clunky old phrase that didn’t work in lots of instances. I had to come up with some snappy alternatives and use them sparingly. ‘Stiff’ is a good word, but you can have too much of a good thing.

HV: You obviously have a very special connection with Alia. Do you work closely with all your authors?

SH: I’ve said it before, but it is true that to know Alia is to love her – she is humble and has a healthy irreverence for the literary world, yet is also incredibly gracious, generous of spirit, and infectiously passionate about reading and literature. She thinks and cares deeply about humankind, about histories and stories (historias – it’s the same word in Spanish), about what is right and good, and why we behave in ways that are neither right nor good. She’s funny but never flippant, and this comes across in La resta (and I hope in The Remainder). I love it when there is understanding between me and the authors I’m translating. I am from the school of: an author’s input can improve a translation. It’s not detrimental to the translation if you can’t rely on it, of course, but I always suss this out early and if they want to be involved in the translation process, I welcome it. In truth, I suppose I feel like some of the responsibility becomes shared. There is always some guesswork involved in translation because good literature necessarily contains ambiguities. When you read a novel, you read it with all of your history weighing on your interpretation, but this doesn’t really matter. When you translate, it does matter, because you will share that interpretation with others. Actors put on accents and so must we. To spend time talking with the author is one way I shed my accent and get closer to theirs. All this being said, some authors really just want to leave it to you (this will sound terrible, but I definitely would if I were an author), and in such cases I merely send a list of questions and never bother them again. So I’m lucky that I now count Laia Jufresa, Rodrigo Hasbún and Alia among my best friends. Close reading is as beautiful a basis for a friendship as I can imagine.

HV: It seems that women’s voices from Latin America are being heard much more in English than before. Do you think there are specific reasons for this?

SH: Women’s voices in many fields and in many languages and places are being heard louder. This probably explains the phenomenon you describe. But let’s not beat around the bush: it is thanks to the concerted efforts of women that women are being heard. And the problem has not gone away, of course. Many have pointed out the blatant gender-ghettoization in the literary world, and I don’t have the answer for how to create gender parity without playing the numbers game, without employing positive discrimination: separate women writer lists, prizes, panels, blogs and projects and so on. But I do think that, in some cases, somewhere along the way, Woolf’s “room of one’s own” has been taken detrimentally literally.

Looking back, the Boom of the 1960s and 1970s introduced some magnificent authors to the world, but its gender imbalance was scandalous. A scandal symptomatic of the times, yes, but scandalous nonetheless: women writers in Latin America were – and to some degree still are – the collateral damage of the deafening acclaim received by its entirely male cast. What is the opposite of boom? I can’t think what that might be. Does such a concept exist? If not, that might tell us what we need to know about how women writers from Latin America have been received, internally and internationally. Today, it’s unlikely that an analogous movement wouldn’t include women writers. But gender equality to me doesn’t mean always finding an equal number of women and men to read, review, publish, laud. It is about calling out injustices in order to slowly forge new taboos: for example, the taboo of talking over or speaking for women.

A truly wonderful thing about literature is that it’s never too late to redress the imbalance: tomorrow you could go to the library and search out, or chance upon, your favourite new author from Latin America. She might be a she. Many of us rely too heavily on the internet when public libraries represent such wonderfully democratic (cookie-free) search engines. What I mean is that every writer has their time to be read. All of those silenced voices are still out there, waiting to be read. It is still perfectly within our power to do those writers the service of reading them.

There’s one last point I’d like to make with regards to the deep-seated misogyny and the physical and emotional abuses committed by too many men in the Latin American literary industry. The problem is endemic (although by no means unique to Latin America) and it has a deep impact on who gets published, publicised and read, but also on what women write, and which women write. When I lived in Latin America I was unlucky enough to see a GIF going around of an adult film star being penetrated from behind by a man, and an accompanying line referring to a contemporary woman writer and an editor, insinuating, of course, that she owed her publishing successes to offering sexual favours to influential men. I’m sorry if that’s graphic. I was sorry I had to see it. But now I’m not. A reader created that GIF for a very niche audience. Not some bored teenager trolling the girl he fancies at school. A reader of “high literature”. I use the grim GIF tale to remind me what women face whenever they sit at their desks to write: the blank page is the least of it; it’s when their page is full that the battle begins. Perhaps it is our duty to do those writers the service of reading them. Relatedly, my colleagues and I have experienced unwanted and uninvited advances from male writers who seem to have trouble distinguishing our job as translators (to read them closer than anyone else) with another kind of intimacy. This rather makes you not want to be good at your job. To shrink into yourself. To evaporate on the page. To fall silent. There you go: the opposite of ‘boom’.

HV: And finally, the nature of publishing is that what we’re reading now is something that you worked on some time ago. What are you currently working on, or excited about?

SH: I’m currently translating a novel by Fernanda Melchor: Temporada de huracanes (Hurricane Season, Fitzcarraldo, UK| New Directions, US, 2020). It’s a masterpiece. I have night sweats from the responsibility of translating this novel.

And I’m co-translating, with Juana Adcock, Giuseppe Caputo’s debut novel Un mundo huerfano (An Orphan World, Charco Press, UK) which manages to be many things as once: a love letter between a father and son, a seething yet humourous portrait of lives lived in poverty, and a refreshingly (sometimes shockingly) honest reflection on the body as a space of pleasure and violence.

Read ‘A Bitter Pill’, Sophie’s translation of a short story by Alia Trabucco Zerán, in the April 2019 issue of Words Without Borders.

Sophie and Alia talk about their Man Booker International shortlisting on the Man Booker website.

The Remainder is published in the UK by And Other Stories, and will be released in the US by Coffee House Press in August 2019.