Translated from the French by Ros Schwartz (Les Fugitives, 2019)

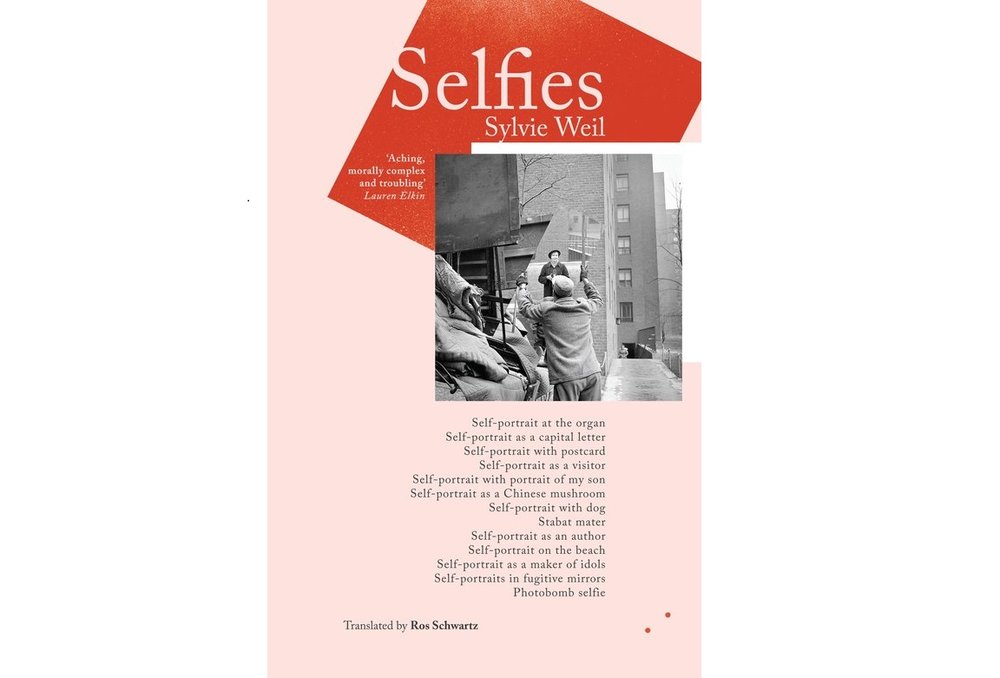

Selfies is a thoughtful take on a modern obsession: in it, Sylvie Weil offers a series of vignettes inspired by self-portraits of women throughout history. Each snapshot describes a self-portrait that evokes for Weil a comparable tableau in her personal memory, which she describes before giving us a glimpse of its importance in her life. This creates an intimacy and familiarity, explaining the detail not only of the photograph itself, but also of all the concomitant personal memories and anecdotes that the image evokes for the storyteller.

The subjects of the selfies range from milestones in Weil’s life to recollections of incidents that might seem more minor, but they all have in common a quick wit, a keen sense of irony, and an immense capacity for compassion. A heady love affair comes to an end with a big decision and a faint hint of regret for a life imagined that will never now be lived (“I’ll watch the dawn break over the red bricks of Harlem. I’ll fasten my suitcase and put water in the kettle to boil. I’ll hastily drink a cup of Nescafé, sparing a brief thought for the students for whom I’ll never pour tea”); Weil’s feelings of irritation towards a pair of American friends surface when they make a selfish decision about their pet (“When you take a dog to the vet to have him put down because he’s guilty of swallowing a plastic duck, he’s obviously got no chance of making it”); the joy of friendship is explained with the brief yet poignant comment that “she gives me the most wonderful gift anyone can give: belonging.” These incidents are connected to more significant revelations about Weil’s life: her need to belong and her passionate attachments belie hints of tragedy elsewhere in the snapshots. In ‘Self-portrait as a Visitor’ we find out that Weil’s Jewish family fled France in 1941 to escape persecution, and learn that Weil’s mother, despite coming from a distinguished family, is always haunted by the “refugee” tableau and passes on to her daughters “nostalgia for a childhood that was not ours.” Later, ‘Stabat mater’ deals with Weil’s son’s mental illness, and ‘Self-portrait as a maker of idols’ reports his disfigurement after a hate crime: the son recurs repeatedly in Weil’s tableaux, exposing Weil’s helplessness as a mother who cannot protect her child from history, from the present, or from other people (perhaps most piercingly evident in ‘Self-portrait with portrait of my son’).

Ros Schwartz conveys all the atmospheric melancholy in her beautifully measured translation, eschewing superfluous detail and offering the fragments of Weil’s life as just that – never a complete picture, but a series of connected representations. Often when reading translations of languages I know, I imagine the translator grappling with a particular choice of phrase, and sometimes wonder why this one was chosen over another. With Schwartz, every time I start to think “I wonder whether X would have worked”, I have the impression she already thought about that, weighed it up, and discarded it in favour of what I’m reading on the page. There is a carefulness to her work, a commitment to elegance and timbre: for example, in a couple of instances, a past participle starts the sentence (“Erased, the photo I wish I could have shown”; “Forgotten, the selfie with the bear”) – these sentences are not typical of English syntax, yet starting them with a subject (think “the selfie with the bear was forgotten”) would lose both the emphasis and the poetry. Schwartz’s rendering is more controlled and evocative, and you know straight away that it’s a choice, not a calque.

The vignettes offer intimate insights into Weil’s personal life but are never self-indulgent, and Weil also weaves in often profound observations on human nature and the difficulties of life: in ‘Self-portrait as a Chinese mushroom’ she shows how a longed-for friendship can turn on a seemingly innocuous comment, and in ‘Self-portrait as an author’ demonstrates how even a celebrated writer can feel humiliated, always dependent on people buying the books and being polite. Perhaps my favourite example of these reflections is the one Weil makes on selfies themselves, noting that “Everyone takes selfies, it’s a way of going unnoticed.” In the act of taking a selfie, what Weil is photographing goes unnoticed because people think it’s “just” a selfie like the millions of others. But Weil is using this 21st-century obsession in order to do something far more important: she is capturing a moment or an observation, or creating a longed-for memory. She is not just a tourist taking a clichéd snapshot, or a mildly hysterical middle-aged woman obsessed with snapping photos of “three scrawny roses with crumpled petals”, a cloud formation, or a family gathering, and yet this is how she wants to appear so that no-one notices her true objective, or realises what she is really capturing with her camera.

With her present-day observations, Weil reaches back to the past: to the women in the self-portraits, to her mother, and to generations of her family who have gone before. She takes as her point of departure something static, and turns it into something shifting and organic, with her acknowledgement that “the past is real and alive.” Unlike the heavily edited and filtered images usually associated with the selfie, Weil’s purpose is not to embellish but to understand, not to distance from reality but to connect. Crossing over from the visual to the verbal, this book is everything that selfies should be: it is not posed or contrived, not about looking her best or showing an over-the-top perfect life. Rather, it is vulnerable, sensitive, beautifully crafted and exquisitely displayed.

Sylvie Weil and Ros Schwartz will be in conversation with Amanda Hopkinson at the Institut Français in London TONIGHT (Monday 17 June) for the official launch of Selfies: book a ticket here.

Review copy of Selfies provided by Les Fugitives; pre-order your copy here.