Translating Women

INTERNATIONAL | INTERSECTIONAL | ACTIVIST | FEMINIST

Translating Women

INTERNATIONAL | INTERSECTIONAL | ACTIVIST | FEMINIST

Posted by Mark

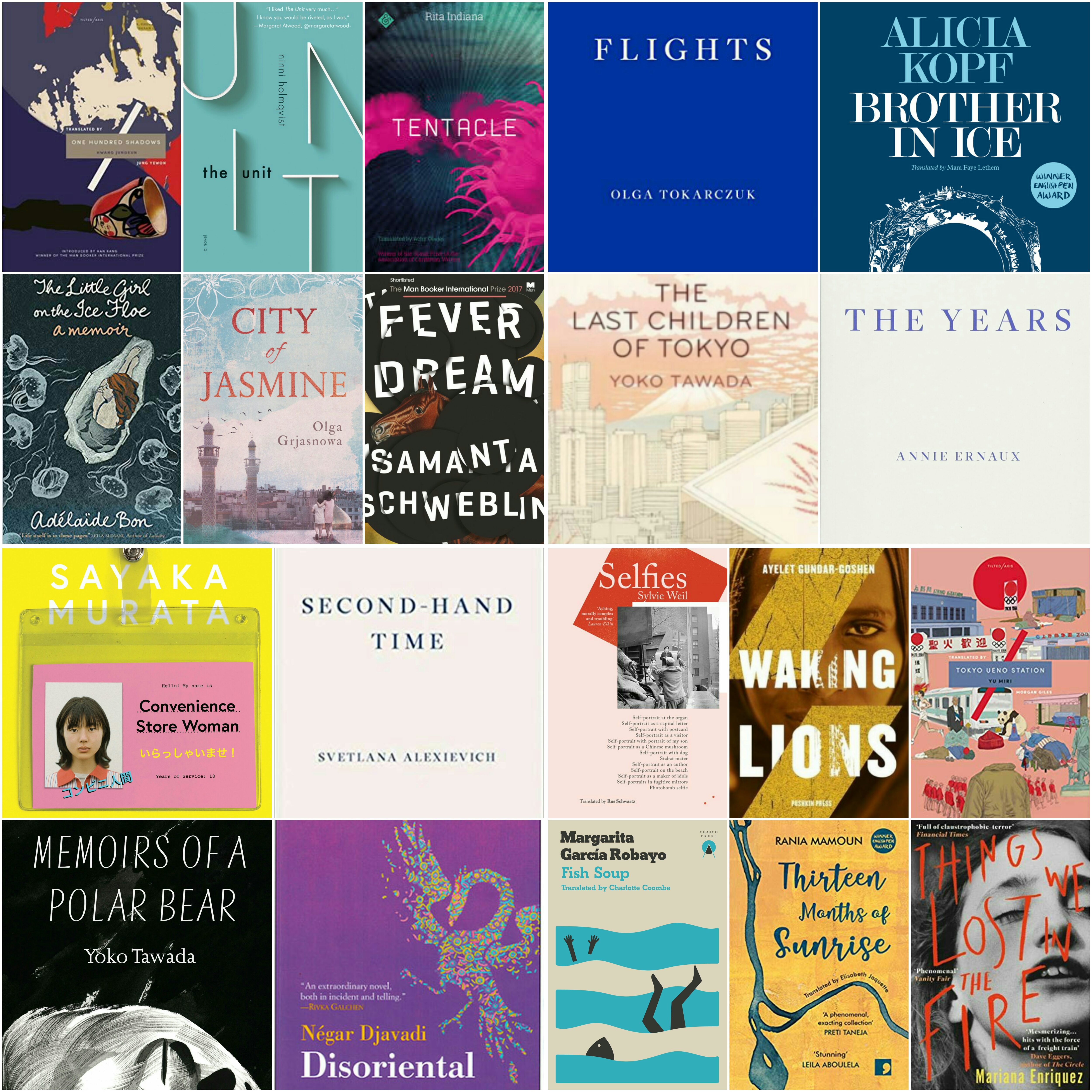

19 July 2019I’m off on holiday for a couple of weeks, and by the time I return Women in Translation Month will be in full swing. This is an online event that happens every August, and is the brainchild of women in translation advocate Meytal Radzinski, encouraging everyone to read women writers from across the world for the month of August. So I wanted to share some reading recommendations: I’ve selected ten categories with two books in each, so there is something for everyone. Whether you’re a seasoned reader of women in translation or just diving into Women in Translation Month for the first time, I hope you will find something on this list that excites you and makes you want to read more.

Things We Lost in the Fire, Mariana Enriquez, translated from Spanish (Argentina) by Megan McDowell, Portobello Books

A collection of spooky, supernatural stories that blur boundaries between reality and horror. Ghosts and demons abound in post-dictatorship Buenos Aires, where women defy tradition and expectation. Perfectly crafted short stories, and utterly terrifying in their ability to slip so deftly from normality to nightmare. Full review.

Fever Dream, Samanta Schweblin, translated from Spanish (Argentina) by Megan MacDowell, Oneworld Books

A frighteningly real supernatural tale; a reflection on – or a warning about – environmental damage, and a terrifying story of power and pain, loss and love. This is a hypnotic novella in which a mother is led inexorably towards an event that will explain why she is lying in a clinic with her life spilling out of her, struggling with her last breaths to save her son from a fate that truly is worse than death. Full review

Flights, Olga Tokarczuk, translated from Polish by Jennifer Croft, Fitzcarraldo Editions

A genre-defying masterpiece about movement, both outside and inside, physical journeys around the world and psychological journeys within oneself, nomadism, spirituality, connections – with places, people, ideas – and a rallying cry against capitalism and consumerism. Not an easy read, but an extraordinarily beautiful one. Full review

Brother in Ice, Alicia Kopf, translated from Catalan by Mara Faye Lethem, And Other Stories

A profound reflection on writing, relationships and self that juxtaposes the inward processing of living with an autistic brother and polar expeditions. It sounds as though it shouldn’t work, but it does: if epic expeditions seem ridiculous – journeys to the most inhospitable reaches of the planet in order to “lay claim” to a space no-one will ever visit – then Kopf turns them around, seeking to understand rather than to conquer, and charting new territory of her own.

Fish Soup, Margarita García Robayo, translated from Spanish (Colombia) by Charlotte Coombe, Charco Press

Two novellas and a collection of short stories present female characters determined to take control of their bodies but corseted in the norms of a society they cannot escape. In “Waiting for a Hurricane”, the narrator despises her home and is increasingly desperate to leave; the collection of short stories “Worse Things” offers snapshots of disintegrating families and bodies; the novella “Sexual Education” is a bitingly hilarious account of sex education at a Catholic girls’ school in 1990s Colombia. Uncomfortably and uncompromisingly brilliant: a gloriously grotesque reinvention of the “anti-heroine”, and a pitch-perfect translation. Full review.

Thirteen Months of Sunrise, Rania Mamoun, translated from Arabic (Sudan) by Elisabeth Jaquette, Comma Press

The first major translation of a Sudanese woman writer. Urgent, thoughtful, occasionally surreal short stories reflecting on love, contingency, broken promises, despair, religion and corruption. Mamoun offers a rich fresco of life that is at once deeply embedded in her culture and universally recognisable: we meet women struggling to support their families, people cast out to the margins by love, by society or by illness, and relationships in many different forms. Full review.

Memoirs of a Polar Bear, Yoko Tawada, translated from German by Susan Bernofsky, Portobello Books

Three generations of polar bears talk about their lives in this offbeat gem. From the self-reflective memoirist grandmother who narrates the first part, on to her dancing circus performer daughter whose life is chronicled by her trainer in the second section, and finally to the baby polar bear whose first months are recounted in the final part, Yoko Tawada blurs boundaries between human and animal, reality and fiction, love and ownership. Full review

Convenience Store Woman, Sayaka Murata, translated from Japanese by Ginny Tapley Takemori, Portobello Books

Quirky in the best possible way. A woman who cannot fit into society finds her place working in a convenience store, but her happiness there is threatened by the pressure from the world outside to conform to “normality.” Funny and shrewd, this was rapturously received last summer, and if you haven’t yet read it you’re in for a real treat.

Tokyo Ueno Station, Yu Miti, translated from Japanese by Morgan Giles, Tilted Axis Press

A haunting novel about the fate of those on the edge of society: a homeless man dies in Tokyo’s largest park, and finds himself trapped there in the afterlife. His story is intertwined with that of the Imperial family in this sharply observed account of the radical divide between rich and poor. Magical, poetic, beautifully translated, and with a searingly exquisite ending.

City of Jasmine, Olga Grjasnowa, translated from German by Katy Derbyshire, Oneworld Books

City of Jasmine – the title referring to Damascus – is a moving novel of resistance and refuge in the Syrian civil war, following the entangled lives of three young people whose fate is changed forever by the Syrian uprising as they each in their own way oppose the regime and pay the price. A superb story but also a challenge, a wake-up call, a reminder not to be complacent or to think we understand something just because we have seen a version of it on the news. Full review

Disoriental, Négar Djavadi, translated from French (Iran) by Tina Kover, Europa Editions

A sweeping family saga set in twentieth-century Iran, this epic tale of a family dynasty, political asylum and murder is also a personal story of exile and (dis)integration in Europe via narrator Kimiâ’s coming-of-age and her realisation regarding her sexuality (foretold in the coffee grounds read by her Armenian grandmother). During interminable periods of waiting in the relentlessly cheerful waiting room of a Parisian fertility clinic, Kimiâ composes a narrative that is witty, intimate, ambitious, and exceptional in both style and scope.

Tentacle, Rita Indiana, translated from Spanish (Dominican Republic) by Achy Obejas, And Other Stories

A psychedelic voodoo Caribbean Genesis story collides with science fiction and eco-criticism in a furious explosion of colour and poetry. In a dystopian mid 21st-century Dominican Republic, an ecological crisis has turned the sea to sludge and killed most ocean life: an androgynous maid inadvertently holds the key to survival, but to fulfil the prophecy she must become a man with the help of a sacred anemone. Brutally poetic, experimental, explosive. Full review.

The Little Girl on the Ice Floe, Adélaïde Bon, translated from French by Ruth Diver, Maclehose Press

Adélaïde Bon was a happy, privileged child living a sheltered life in the smartest area of Paris. She was nine years old when a stranger raped her in the stairwell of her building. In this brave and deeply affecting memoir, Bon pieces together the incident that shaped her life, and tries to come to terms with the devastating consequences, to reconstruct the events and so reassemble herself. This stunning book is a quest for truth and for self-love, and an anthem to compassion, humanity and overcoming.

Selfies, Sylvie Weil, translated from French by Ros Schwartz, Les Fugitives

A thoughtful take on a modern obsession that crosses from the visual to the verbal: Weil offers a series of vignettes inspired by self-portraits of women throughout history. Each snapshot describes a self-portrait that evokes for Weil a comparable tableau in her personal memory; she describes this before offering intimate insights of its importance in her life, and weaves in often profound observations on human nature and the difficulties of existence. Full review.

Waking Lions, Ayelet Gundar Goshen, translated from Hebrew by Sondra Silverston, Pushkin Press

A thriller set in the Israeli desert: a promising young doctor is speeding along in his SUV in the middle of the desert after a long shift, when he hits and kills a man. No-one has seen him. Knowing his life will be over if he reports it, he gets back into his car and drives away. But a woman shows up at his door: she is the wife of the man he killed, and she saw what happened. This tale of secrets, lies, extortion and atonement is a powerful, suspenseful, electrifying read. Full review.

The Unit, Ninni Holmqvist, translated from Swedish by Marlaine Delargy, Oneworld Books

A compelling and dystopian debut novel: Dorrit enters the Second Reserve Bank Unit, a luxury retirement home where she can live out her final years free of financial worry. The catch: residents must donate their organs one by one until the “final donation”. Just when she thinks she has accepted her fate, she falls in love and finds reasons to cling to life. Full review

Second-Hand Time, Svetlana Alexeivich, translated from Russian (Belarus) by Bela Shayevich, Fitzcarraldo Editions

Subtitled ‘The Last of the Soviets’, this is an unforgettable polyphonic witness to the tragedies of twentieth-century Russian history: Alexievich interviews and listens to her compatriots as they talk about the history of their country, and reconstruct a painful past through memory. This is an 800-page tome about human suffering, but don’t let that put you off: Nobel prizewinner Alexeivich is an essential read.

The Years, Annie Ernaux, translated from French by Alison L. Strayer, Fitzcarraldo Editions

This ambitious and innovative autobiographical endeavour is a “collective autobiography” that starts from the premise that every memory of every life – from historical atrocity to TV adverts – will vanish at death, and so we must remember, document, and claim a place in the world. This witness to twentieth-century French cultural history told through the life of one woman is a tremendous, poignant, necessary book. Full review

The Last Children of Tokyo, Yoko Tawada, translated from Japanese by Margaret Mitsutani, Granta Books

In the near future, Japan has closed its borders following an environmental disaster: the elderly are immortal and the children are frail. An old man raises his great-grandson, who may be the only hope for the survival of the young. Winner of the National Book Award’s inaugural prize for literature in translation in 2018.

One Hundred Shadows, Hwang Jungeun, translated from Korean by Jung Yewon, Tilted Axis Press

Set in a condemned electronics market in Seoul, this is both a sweet alternative love story and a chilling horror story. Eungyo and Mujae both work in a slum electronics market earmarked for demolition, and draw closer together as the shadows of the slums’ inhabitants start to rise. Eerie and atmospheric, this is a unique social commentary on the divide between superficial modernity and individual expendability.