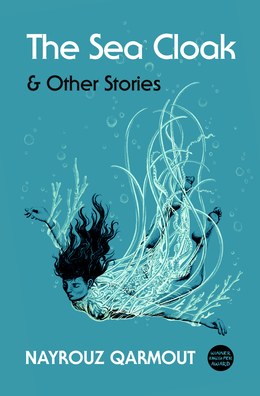

Translated from Arabic by Perween Richards (Comma Press, 2019)

It’s fair to say that The Sea Cloak is one of my most anticipated books… ever. Comma Press first started advertising it last Spring: author Nayrouz Qarmout was to appear at the Edinburgh Literary Festival in August 2018, but her visa application was turned down twice by the Home Office. She just made it in time after the festival intervened on her behalf, and was then invited back this year to take part in a panel on migration and refugees – so publication was postponed in order to launch The Sea Cloak during Qarmout’s visit to the UK. So I’ve been looking forward to this book for over a year, and I can tell you that it was absolutely, unequivocally, 100% worth the wait.

It’s fair to say that The Sea Cloak is one of my most anticipated books… ever. Comma Press first started advertising it last Spring: author Nayrouz Qarmout was to appear at the Edinburgh Literary Festival in August 2018, but her visa application was turned down twice by the Home Office. She just made it in time after the festival intervened on her behalf, and was then invited back this year to take part in a panel on migration and refugees – so publication was postponed in order to launch The Sea Cloak during Qarmout’s visit to the UK. So I’ve been looking forward to this book for over a year, and I can tell you that it was absolutely, unequivocally, 100% worth the wait.

Qarmout was born in a Palestinian refugee camp in Syria and was “returned” to her home in Gaza in 1992, making her a refugee for a second time, but this time in her own country. The Sea Cloak offers insight into life in Gaza, but without melodrama or exaggeration – for Qarmout, this is simply her home, her life, her political context that she is observing. Her background in journalism shows through in her writing: there is nothing partisan here, nothing that tells her reader to think or react in a particular way. Perhaps this is also an effect of her being an “outsider” even in her own country: rather than instructing, she lays out fragments and stories from her context, and offers them for interpretation. There are aspects that hint at autobiography or personal experience (for example, the female protagonists of both ‘The Long Braid’ and ‘A Samarland Moon’ are journalists, the protagonist of ‘The Sea Cloak’ “retreated into the past, to a sprawling camp buzzing with children playing marbles and forming teams for a game of ‘Jews and Arabs’”, and the bombing of a building in ‘Our Milk’ echoes an experience Qarmout describes as being intimately connected to her writing – she forced herself to write one story for every floor that was rebuilt), but the rich tapestry of everyday people presented in The Sea Cloak defies any narrow interpretation of the text as being the experience of only one person – the rhetorical question in ‘14 June’, “How many times has she jumped out of bed thinking that a bullet has punctured her window?” may very well be Qarmout’s own experience, but it is also doubtless the experience of anyone who lives in a warzone. Fictional characters live through real events, such as in this depiction of a restaurant bombing: “The waiter staggers for a moment, still standing in the rear half of the restaurant that hasn’t collapsed. His face gushes with blood – some invisible piece of shrapnel has sliced his cheek – but he barely notices it. All he can do is stare at the splashes of colour that fringe the rubble: strips of tapestry and flesh, both heavy with history.”

Not all of the stories deal with terror and conflict: like Gazan life, these are part but not all of the picture. Many of the short stories have women’s experience at the fore: in ‘The Sea Cloak’, a girl struggles with the transition to womanhood and the restrictions that this forces on her; in ‘The Mirror’ there is the memory of a sexual assault; in ‘The Long Braid’ a schoolgirl is told by her teacher that emancipated women are “sluts”; in ‘Breastfeeding’ a mother and father want something better for their daughter than becoming “entangled in the traditions that they themselves were raised with and could never escape”, only to discover that all options lead to restriction. Life is too often decided for these women, but in many cases other women uphold this patriarchal society. Yet Qarmout’s characters try not to be, or not to remain, victims. These are not stories of misfortune but of life, and the strength of The Sea Cloak comes from not having one definable agenda, but rather a collective one: destinies are interwoven with intelligence and compassion (read ‘White Lilies’ in particular), showing us that we are never truly external to the problems of a region, because they are the problems of humanity.

As for the language and the translation, both are excellent. Qarmout’s writing has a wisdom and clarity, and a richness of expression that is both exciting and compelling. Perween Richards translated all but the title story of the collection (which was translated by Charis Bredin), and she conveys this richness superbly, bringing the text to a recognisable place without ever being untrue to its origins: the translation is careful and precise, yet not overworked. Richards was one of two winners of the Translate at City translation competition in 2016, and as far as I know this is her first major translation – and what a debut it is. This collaboration is a shining example of the best of connections: between people, places, cultures and contexts. The narratives might be shocking in their everyday candour and the lack of melodrama to describe the atrocities that have become commonplace, but there are nonetheless universal messages such as this one from ‘Breastfeeding’: “We all have to grasp at the chances we can in this life.”

This juxtaposition of extraordinary situations and ordinary lives is one of the most striking features of the collection: as Richards notes of Gazan life, “Not everyone is a freedom fighter, most are just normal people trying to go through life with dignity and purpose in the face of impossible odds.” If there is everyday violence, there is also everyday experience – there is a new take on forbidden love in ‘The Anklet of Maioumas’, in which a girl and boy from opposite sides of the border hope to be together; in ‘A Samarland Moon’ two young people who have drifted apart – one towards religion, the other towards emancipation – try to remember what they loved about one another, and young boys work to advance in life in ‘Pen and Notebook’. There is no preaching or overly didactic comment – Qarmout’s characters go about their lives, and their lives just happen to unfold in one of the most volatile regions on Earth. I learnt a lot from reading The Sea Cloak, yet I didn’t feel “instructed” – I think this is a necessary book. We need this book in the west. We need to know, we need not to read only books in which we recognise ourselves. One character in ‘Black Grapes’ asks “When are they going to understand?” – this is the challenge laid down gently by Qarmout. Terror, violence and death abound, yet if there is one thing that truly defines this collection, it is humanity, and that is the connection that rises above all others. As Qarmout stated in her recent appearance at Edinburgh International Book Festival, “Suffering in revolution is a collective experience. I rebel. Then we exist. I believe creation is a revolution. Palestinian identity needs this revolution.” The Sea Cloak is indeed a quiet revolution, and I urge you to be part of it by reading and sharing these stories.