Nicky Smalley is publicist at the pioneering independent publishing house And Other Stories, who champion translated literature and who publicly took up Kamila Shamsie’s “provocation” to the publishing industry to make 2018 a Year of Publishing Women.

Do you perceive an increase in the number of translated works making their way into English?

Yes, there was research released by Nielsen that had been commissioned by the Booker foundation, showing that the percentage of books translated into English had grown to around 5%, and that in terms of literary fiction, translated literary fiction was selling better than non-translated literary fiction. And that is really noticeable in terms of the way that bookshops are responding: independent bookshops in particular are looking for interesting things in translation to sell. 5% is still a very small number, but it’s progress in the right direction.

So do you see booksellers as major gatekeepers then? I always assumed that publishers were the main gatekeepers…

Publishers are obviously gatekeepers to an extent, but different publishers have different degrees of power in their gatekeeping, as do booksellers. A chain like Waterstones has the power to make or break a writer. And although Foyles is no longer an independent bookshop, they played a major role in putting books like Convenience Store Woman and The Vegetarian into people’s hands. If something shows signs of selling well, booksellers will run with it. Independent bookshops can have significant influence: a key part of their role is to develop a relationship with their community, and if they are prioritising a certain kind of book, they’re doing that because they know that the community around them is interested in that. There are certain booksellers that we work with as much as possible because we know that they understand our books, and that their buyers understand our books and understand why they’re being sold in that bookshop: one of the most important things about bookshops is that they provide a context.

What about the books that you choose at And Other Stories; you publish a lot of translated literature – do you have a set quota of translated works?

We would never not publish something because it didn’t fit in with the statistics of what we publish. Generally each year we publish around 70% translated literature and 30% English-language. That varies from year to year depending on what we like, but it is important to us that we have a mix. It would be unlikely that we’d have a year without publishing some English-language writing. We don’t want to be pigeonholed, and we don’t want translated literature to be pigeonholed as a genre: by publishing both translated and non-translated writing, it means that the translated writers that we publish occupy the same space as the non-translated English-language writers, and that’s important to us.

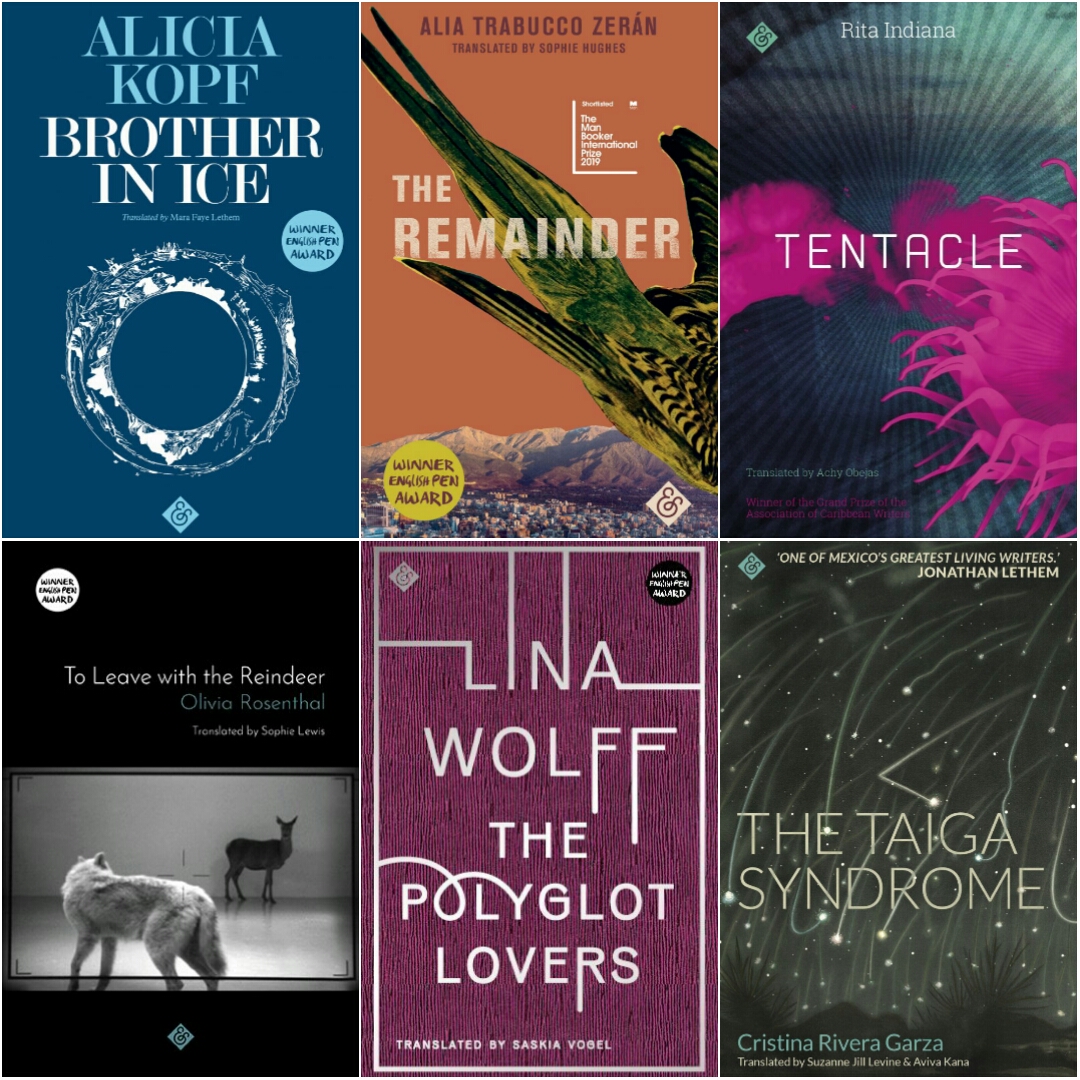

Let’s talk about The Remainder; can you tell me more about its journey from commission to publication to Man Booker International shortlistee?

The Remainder, as far as I understand it, was sent to us by (author) Alia Trabucco Zerán’s agent Laurence Laluyaux at RCW. Laurence is an amazing agent and she works very hard with her authors; she’s very focused on developing their careers and supporting them through the publishing process, and she regularly sends us things that she thinks might work for us. Then we talked to (translator) Sophie Hughes at the London Book Fair and she had written a sample; the pairing of Alia and Sophie was there from the beginning.

Was it specifically for the Year of Publishing Women that you took on The Remainder, or was it just well-timed?

We would have published it anyway, but when we acquired it we knew it would work well in the Year of Publishing Women because it’s such a strong book. Alia was very enthusiastic about the concept of the Year of Publishing Women, so it was a natural fit.

There are beginnings of a move away from eurocentrism in translated literature, and your catalogue last year had quite a lot of titles from Latin America. Is this a deliberate trend, and something you aim to foster?

We’ve always published a lot of Latin American literature; over the first few years that And Other Stories existed we published a lot of Latin American men, and when we decided to do the Year of Publishing Women, one of the things we set out to do was to find Latin American women writers. We have also focused on trying to diversify the countries within Latin America. There’s Alia from Chile, Mario Levrero from Uruguay, we’ve got a Columbian writer, Cristina Hernandez, coming out next year translated by Julia Sanches, and there’s Rita Indiana who’s Dominican, and we’re always interested in Mexican writers because they have such a rich literary heritage. And we’re constantly looking for writers outside of European languages: a lot of the books we publish might not be from Europe, but they’re from European languages, and so we’ve been keen to look at more Asian and African writers. For the Year of Publishing Women we looked for African women writers in translation from non-European languages, though we didn’t come across anything that worked for us. The move outside of Europe is important, but part of the challenge of it is that a lot of European countries have funding schemes for translated literature, and unless you’re publishing commercial literature it’s very difficult to fund translation, and the funding isn’t that widely available in the UK. There’s the PEN Translates scheme, which is fabulous, and they’re very keen to incorporate diversity in what they fund. Perhaps that has had an impact on the kind of things that people are looking for, because if there’s an awareness that people are looking to fund non-European writing, then publishers might be more likely to seek it out. One of the ways Eurocentrism could be overcome is if there were more sources of funding to fund translation specifically from non-European countries. Hopefully the debates about diversity over the past few years have opened peoples’ eyes to the need to hear other voices and to enable other voices to be heard.

What do you perceive as the greatest challenges regarding gender bias in translated literature, and what do you think might usefully be done to respond to and overcome such biases?

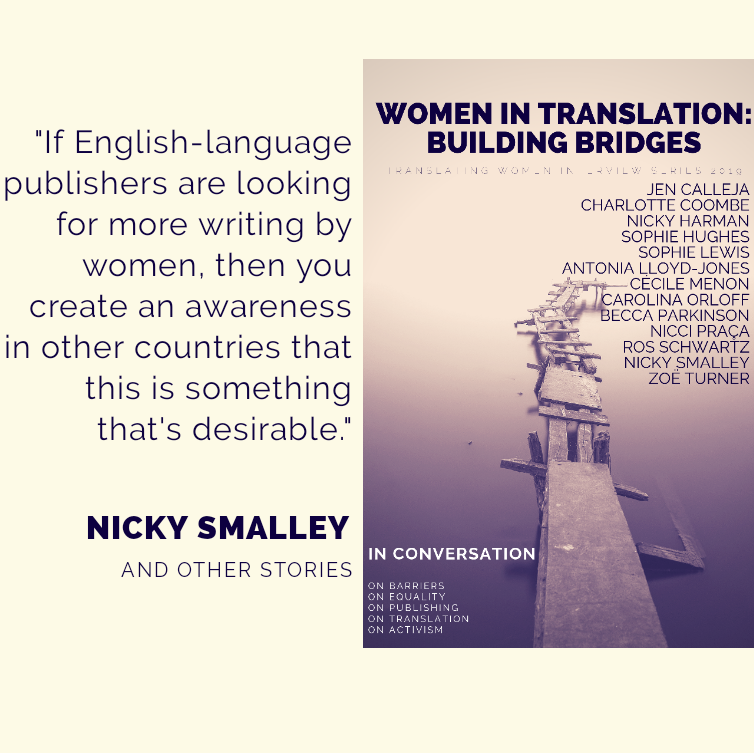

With translation specifically, there’s a real issue of women in other countries not necessarily getting the acclaim that brings them to our attention. This is definitely not an excuse, but it’s something that most publishers – maybe us slightly less because we take a lot of submissions from translators and we are in touch with a lot of translators who tell us about things they’re excited about – but for larger publishers who work more on an agent basis, if those women writers in other countries are not getting the acclaim for their writing that they deserve, then they’re not going to find agents who will take them into English. So that’s a key issue. And it’s a push and pull thing, because if English-language publishers are looking for more writing by women, then you create an awareness in other countries that this is something that’s desirable. But there is still a problem with women’s work not being taken seriously enough, and that’s not something that’s going to change in a couple of years. What interests me is that you get these initiatives started, and we’ll talk about it a lot for a couple of years, and then it blows over and everything goes back to normal.

How has the Year of Publishing Women had a lasting impact for And Other Stories and, hopefully, more generally?

I’m not certain what impact the Year of Publishing Women had on our sales; often sales totals are more dependent on a particular title doing well rather than our titles doing well across the board. Certain titles from last year did really well, and may not have done so well if it hadn’t been for the Year of Publishing Women. Rita Indiana’s Tentacle, for example, sold almost 4000 copies; a lot of people bought it because it was a very timely exploration of queer identities and environmental issues. I’m pretty sure we would have published that book anyway, but it’s possible it wouldn’t have come to our attention without the Year of Publishing Women: we asked Yuri Herrera if he could recommend any Latin American women, and he told us we had to publish Rita Indiana. And if we hadn’t been doing the Year of Publishing Women, it’s possible that we wouldn’t have asked him. So that’s one way it’s had a positive impact. It would have been great if everyone had rushed out and bought our books all year, but we did see a spike in subscriptions and a lot more direct sales; we did a few things like bundles of Year of Publishing Women books that sold quite well. So I can tentatively say that in terms of sales it had a positive impact. But in more general terms, the proportion of women being published is increasing; people are putting more attention into their acquisitions to try and balance things. And I’m not saying that was necessarily our achievement at And Other Stories, but we raised awareness of it and started a conversation about it.