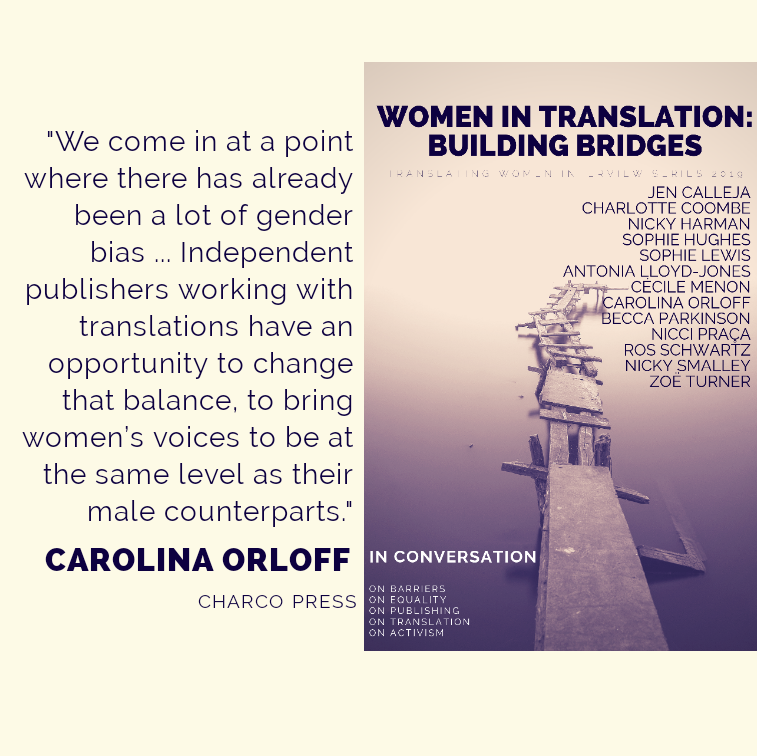

Charco Press is an award-winning young independent publishing house based in Edinburgh. Run by Carolina Orloff and Samuel McDowell, Charco publishes the most exciting new fiction from Latin American in translation. I spoke with Carolina about the translator’s visibility, smashing preconceptions of translated literature as being “niche”, the triple marginalisation of Latin American women writers in translation, the activist work of Charco Press, and their commitment to redressing the balance.

You set up your publishing house in 2016, with your first titles published in 2017. Charco Press is growing in exciting ways: how have you perceived this evolution since your beginnings, and what are your plans and hopes for Charco’s future?

At the time we started Charco we sensed there was a slow turning point in the appreciation of translated fiction; there had certainly been a progressive change for the better that’s still happening. We feel that because of that change in the reception and the perception of translated literature, Charco has gained attention quite quickly. And we hope that this change will continue to grow: I think it’s to do with that openness in readers’ minds in understanding translated fiction not as translated fiction per se, but just as fiction. And that’s one of our aims: not exactly to change perceptions, but to encourage the reader to understand that what we’re trying to do is not raise awareness of translated fiction, but to publish fiction because it’s good fiction.

And that separation, that subcategory, is one of the greatest barriers, isn’t it?

Yes exactly, because on one hand we’re always keen to give prominence to our translators by naming them on the cover of our books, but on the other hand we want to overcome this block from so many readers in relation to translated fiction, that they would immediately understand it as something that’s niche, difficult, too complex, and we want to prove that that’s not the case. So it’s a balancing act with every book.

Your mission statement is “learning to read again”. Could you talk more about what this means to you and to Charco?

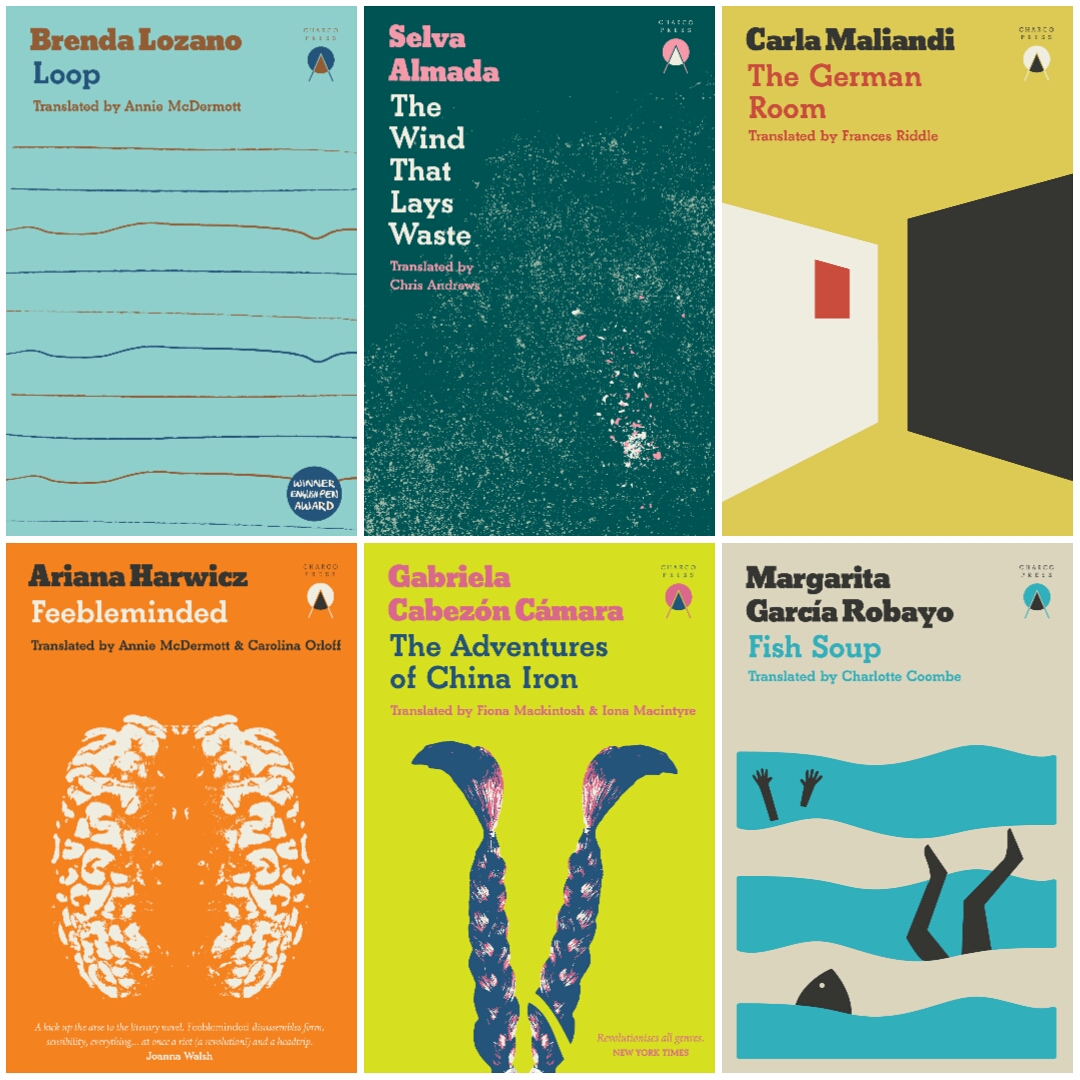

That comes back to this idea of debunking certain preconceptions of translated fiction in general, and Latin American literature in particular, so that we learn to read again – it might be ambitious, but those are core elements for us. In 2017 we launched with five books rather than one or three, against the advice of a lot of people in the industry. It was very important to us to make that statement, to put out there five authors not just from the same region but from the same country in Latin America – from Argentina, in this case – and from the same generation, and show how different they are. So the mission statement of learning to read again is to go against the misconception of translated literature as being niche or difficult, and also against a very stereotypical idea that Latin American writers are still doing magical realism, or telling stories about big families and so on. We wanted to break against those two very ingrained ideas and propose something different and very immediate.

As well as actively seeking out debut authors and emerging translators, you also actively seek out work by writers from less represented countries or cultures within Latin America. Can you tell me more about the importance of this commitment to diversity?

Yes, that should be our next mission statement! Latin America is a huge, incredibly diverse region. That’s why it’s frustrating when it all gets put together into the same bag and transported to the English-speaking world. Someone from Guatemala telling their story or their reality is completely different from someone from the south of Chile, for example. And I think our commitment to diversity has to do with that, trying to bring into the English-speaking world that almost irreconcilable diversity that exists in Latin America. But at the same time we don’t want to make too much of a big deal out of that geographical focus, because again we want to concentrate on the literature itself. We want the books and the stories to speak for themselves. So we’re trying to find a balance of portraying our best selling point, which is that we publish books from Latin America, but at the same time underlining the fact that these are amazing stories universally speaking.

How do you identify authors to publish, and translators to work on them?

There is a lot of instinct involved. I don’t have a formula; we focus on authors – including debut authors – who have something to say that has had an impact in terms of debates in society, something that goes beyond the book or the literature that they’re producing. All of the Charco books so far stem from an impact in the societies of origin that I hope will translate into the English-speaking society. They bring philosophical questions, universal questions that are important for all of us. And the translators have to understand, have to have a relationship with the story, the book, the universe that they’re going to translate, that is beyond the semantics of the language, that they’re interested in and passionate about, because that’s what makes a good translation.

You’ve also published a good number of women writers. What do you perceive as the greatest challenges regarding gender bias in translated literature?

This is a tricky and important question. From our perspective, we come in at a point where there has already been a lot of gender bias. Generally speaking, what gets published in Peru, for example, has come through a completely biased and male-dominated process. So when a female author makes it and gets published, there are already dozens who were left behind. Independent publishers like Charco working with translations have an opportunity to change that balance, to re-balance as it were, to bring women’s voices to be at the same level as their male counterparts. I don’t even think about it to an extent, for me it’s about the stories and the literature, and if one year we have more female authors than another year that’s okay, it shouldn’t be a big deal.

Is there anything else that you think might usefully be done to respond to and overcome such biases?

This is a great question, although I don’t have the answer! One of our ambitions is to work towards publishing books for children written by Latin American writers in translation. Coming from Argentina, I grew up reading books in translation without even realising they were books in translation, and that meant that from an early age I was reading different voices of the world that were being put into my universe and expanding my universe from very early on. And I think that’s a great and very simple way to foster the idea not only of gender equality but also of a more diverse world. Independent publishers working with translation are doing a great deal in the sense of trying to give a voice to women writers from different areas of the world outside of Europe, that not only need to be heard in English, but also because English is a gateway to so many other languages, to create an opportunity for those books, those voices, to go beyond their country of origin and to go beyond English to get to other parts of the world.

Do you perceive an increase in the number of translated works making their way into English?

It’s a good time for translated literature. It’s growing; I think there’s a shift for the better, even though reality is shifting the other way. There’s a demand from readers, a counter-reaction to the closing of boundaries; it’s a good time to be translating and to be reading translated fiction. And if I’m going to be ambitious, it’s also a good time to think about not just the bookshelves, the publishers and the readers, but about education. There needs to be a different understanding of the importance of languages in the education system in the UK; it’s very easy to be an English speaker, but learning a language is opening a door to another universe. I think the fear of languages is linked to the fear of translated fiction.

There are beginnings of a move away from eurocentrism in translated literature, which you are a significant part of – how have you perceived this over time, and how do you think we can foster it?

More supply! But the key question also is how to generate the demand. In the UK there are slowly but surely more prizes, and they can make such a difference to a book or a region. We’ve had a lot of support from small independent bookshops, but there needs to be a bigger movement from bigger companies, where they give more prominence to other regions or small publishers, because if you don’t see a book then you might not buy it. If Waterstones, for example, give prominence to a particular publisher it can have a real impact. So we can only hope. We need to provide a more diverse array of fiction and worlds and voices for people to read – or not read, but our commitment is that they should be there.