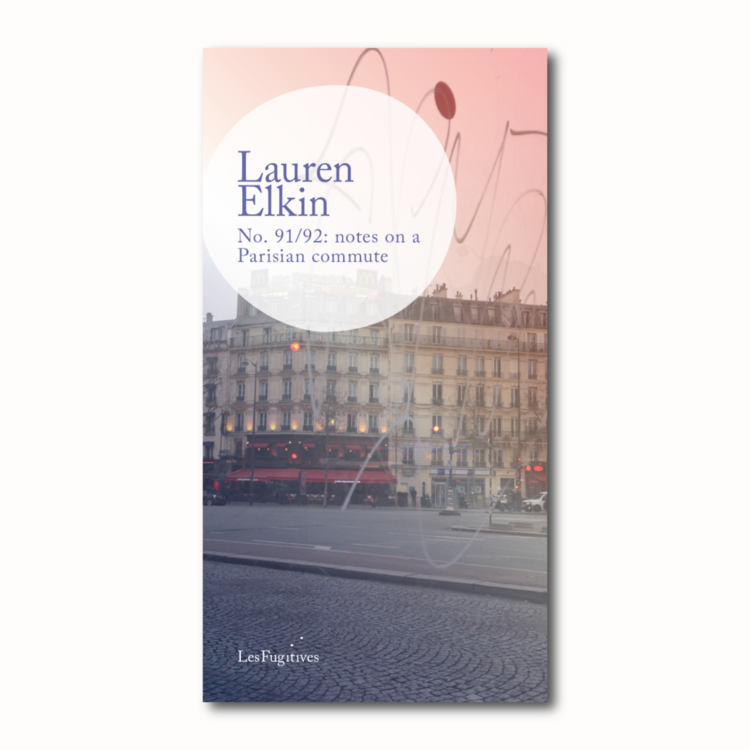

Les Fugitives, 2021

No. 91/92: notes on a Parisian commute is the first book Les Fugitives have released that wasn’t originally written in French. It is, though, steeped in both the language and the context: Lauren Elkin explores Paris in the aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo terror attacks from her seat on a commuter bus, and intertwines the common experience with an extremely personal one of loss and searching for place.

I’ll come out and say straight away that I loved this book – it’s my favourite from Les Fugitives since the wonderful Selfies in 2019 (Sylvie Weil, tr. Ros Schwartz and reviewed here). It has in common with Selfies its focus on snapshots, on personal experience as connected to (but never representative of) a universal one, and its subversion of the memoir as a genre. It also subverts expectations of the way in which we use mobile phones: instead of looking down at her phone to close herself off from what is around her, Elkin deliberately points it outwards, using it to record her observations of the everyday and the extraordinary, and how the boundaries between the two are blurred in the face of personal and collective tragedies.

The first thing that struck me about No. 91/92: notes on a Parisian commute was how familiar Elkin’s descriptions were. My commute used to be on the 95 bus, and I was swamped by memories of past times. Normally this wouldn’t necessarily be a selling point to me – I don’t particularly want to see myself reflected in what I read – but there was something very emotional about reading experiences so familiar to me and yet now so far in my past. Yet I don’t think the book would be less easy to connect with if you didn’t have this sense of familiarity – it is very personal, but not to the point of introspection that excludes the reader. On the contrary, it is intimate and inclusive, as Elkin invites us into her tiny space on public transport and the vast space of her thoughts.

There are some amusing and borderline philosophical observations about “bus etiquette” (my personal favourite was an interrogation of the guilt experienced when sitting while others stand). There are also some very honest reactions to the outfits and behaviour of fellow passengers, and exasperations with the shared experience of the bus (not to mention with the efficiency of the network itself). Yet although these are necessary for the full experience of the text, they are not its main interest: this, for me at least, was in the searching to articulate the unspeakable, and to make sense of the incomprehensible, to “pattern the world” through repeated journeys and so give structure to the chaos of senseless tragedy. In the immediate aftermath of the Charlie Hebdo attacks, Elkin writes:

“We’re all thinking the same thing, it’s the first day back to work since it all happened …

we try to get on with things even though there are seventeen fewer Parisians than there were this time last week”

The sense of solidarity is palpable, as is Elkin’s own searching need to connect with her fellow passengers, or perhaps with her adopted city (or maybe the two are inseparable). “Ah Paris”, she laments, “I want to make it all better, smooth your rumpled pavement, kiss the hot forehead of Sacré Cœur”; the quasi-maternal longing to soothe away the pain endured by the city and its inhabitants is achingly entwined with the experience of an ectopic pregnancy.

The use of the everyday to understand the unimaginable is not arbitrary: as Elkin reflects, it was precisely the right to an everyday that the terrorists robbed their victims of. This kind of profound observation is simultaneously what draws together the reflections on the people encountered and the experiences traversed during the “dead time” of a daily commute, and what elevates this text beyond a diary and into something altogether more universal in its significance. In the epilogue, Elkin comments on the timing of this book’s publication, and her decision to revisit the “bus journal” during lockdown: it is prompted by a kind of nostalgia for “the days of sharing space and air with strangers.” Within the pages of her No. 91/92: notes on a Parisian commute, she makes this possibility come alive again.