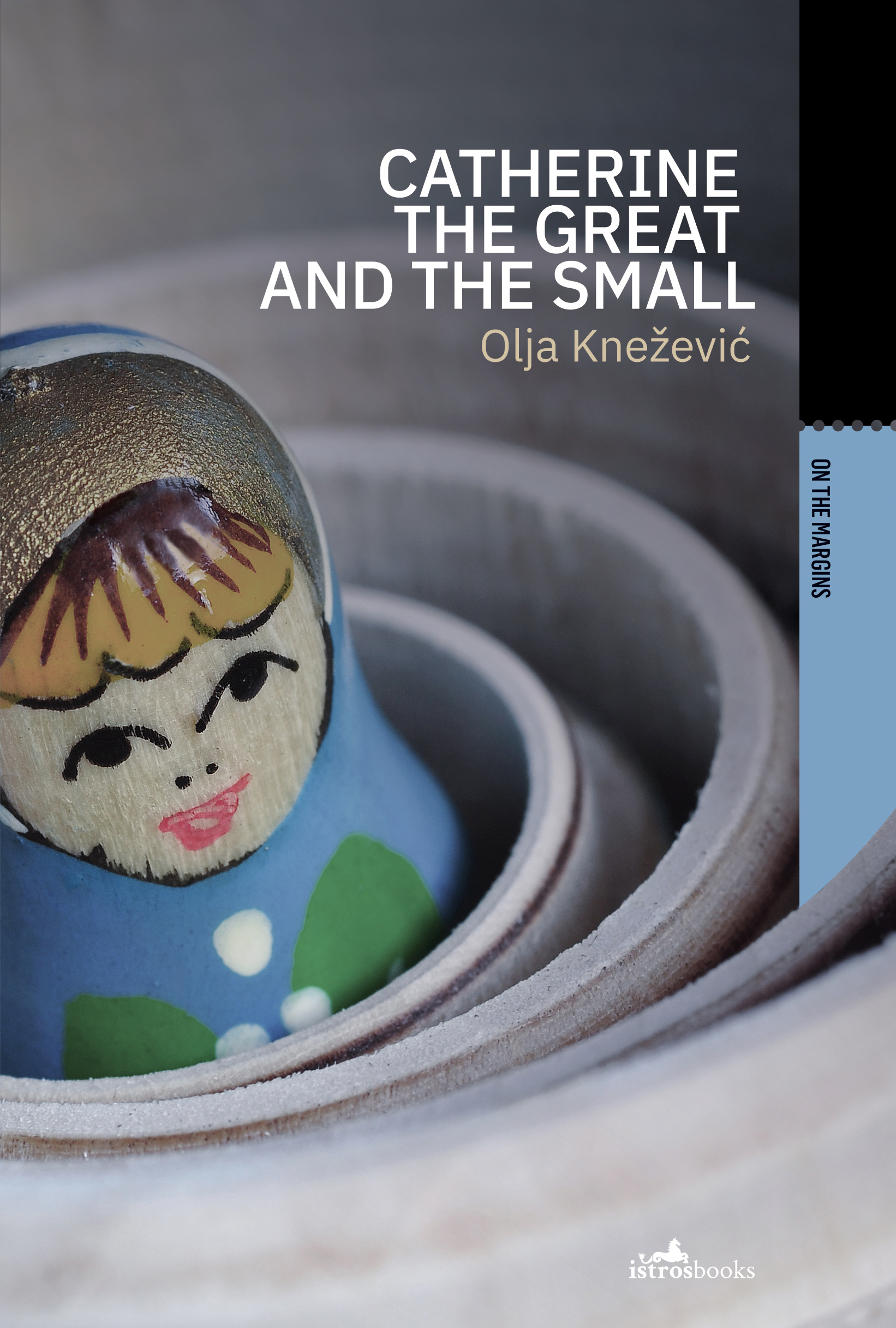

It’s my great privilege to bring you the second instalment in my three-part interview series about new Montenegrin novel Catherine the Great and the Small. Today author Olja Knežević talks about her book and its journey to publication in English with Istros Books (translated by Paula Gordon and Ellen Elias-Bursać). Catherine the Great and the Small is published TODAY, and you can find out more, or purchase it, here.

You self-published your previous book (Milena & Other Social Reforms) in English; did this help to circulate your work in the English-language context? How has it been different working with translators and an English-language publisher?

Olja Knežević: Milena & Other Social Reforms was my first novel, published in 2011, and what an unusual path it had! It was originally written in English, obviously not my native tongue, because I developed it from a 20,000 word dissertation for my MA in Creative Writing at Birkbeck College in London. The dissertation won Overall Prize as the best MA dissertation that year, and I went on, wind in my sails, to write the whole novel in English, from the point of view of Milena, a rebellious young Montenegrin, who had to escape to London to save her life. I was hoping to find a UK publisher. It was taking time, so in 2011 I gave in to the pleas from Montenegro, my home-country, to publish that novel there, but in Montenegrin, of course, so I had it translated into my own native tongue by someone for a modest fee. It was published by the only publisher who was independent from Montenegrin Government, because Milena is a politically engaged novel, inspired by a true story. I knew that the book would have to travel just by word-of-mouth publicity, but it seemed enough at the time. It was sold out in three weeks after its release, and is still selling. Milena has found her place in the world, an underground place, so befitting for the type of character she is. I decided to put the English language version online, and just leave it there, to find its own path.

Catherine the Great and the Small is my fourth book, and the first one to win a big regional prize, be finally noticed and picked up by its UK publisher, Istros Books. It’s a completely different world from the one of self-translating and self-publishing; with editing, proofreading and the details of translation paid close attention to, and seriously discussed between professional team members. I think the English language version of Catherine is phenomenal, and, now, that I see how it looks when a novel is professionally translated and edited, I feel sorry for Milena.

Catherine the Great and the Small is a book about women – their emancipation, their restrictions, their relationships with each other, themselves, their country (and some pretty useless men) – do you consciously view your writing process as a feminist act?

No, I don’t consciously, deliberately, view my writing as a feminist act. Not long ago, however, I realised that I have lived a feminist life since I was a young girl. First, of course, through my mother, who instilled in me the standpoint that a woman can desire to belong to herself first, to be ambitious, outspoken, a leader and an organiser, a proud owner of her own time to even rest, to even have fun. My mother’s actions and character have shown to me that a woman can venture into men’s territory, and remain authentic there – all this while staying married to a man’s man, who she loved passionately and fought with for equality at home on a daily basis. This has formed me, and then let me travel my own road, to make my own choices and mistakes. My writing has not been an escape into pretend-worlds – it’s been the best tool to reach my consciousness when it seemed like everything else had conspired to make me forget myself. In there, in my consciousness, I’d find strong and interesting women, their relationships with each other, their community, their men. And I’d write down their stories, in order to keep belonging to my true self.

Catherine the Great and the Small is rooted in a particular time and place; how important was it to you to keep Montenegrin culture and recent history – and particularly the loss that came with the wars in the Balkans – at the centre of Katarina’s story?

I was going to write about a woman whose life is parallel with mine, so, yes, it was important. She was not going to be me, but she should be like a close friend, with a similar destiny. In a way, writing about her life, I was writing down the collective memories of the country I have known. That’s why I wasn’t going to experiment with the form, because there are no novels on the subject as simple as a contemporary woman’s life, written down intimately and sincerely, from Montenegro. It has always been so inspirational for me, how we lived in a socialist community where, in what was then the Republic of Montenegro, we had this mixed Balkan and Mediterranean mentality, where everyone knew everyone, we lived outside, and felt free there, on the streets, socialising passionately, loudly, judgmentally, with candid vulnerability. Yet never in history were we institutionally free. Having been somewhat “in the middle”, we knew how things were in the West and in the East, and we liked our kind of “free.” Our women, after WW2, when they had become revered as true heroines, had equal rights, had equal pay for equal work, until the 1990s, when everything fell apart. Now, I’m not saying it was perfect. It was a one-party system, after all, but women could be optimistic that the future was going to bring more and more progressiveness in their social status. It never happened. Instead, enter the 1990s and the war. Women were pushed down the ladder. Always the first victims of war, women, because we don’t want it, but we immediately regress into being seen primarily as reproductive organs that bear and support the real heroes – men. That’s such a difficult and interesting conflict, a personal and political one, which makes for great material.

Katarina is always capable of finding the “ball of light” in the depths of misery – what message does this give for readers of your novel and why was it important to you that she should have this strength?

I’m glad you mentioned that image. That’s Katarina, her main strength. Most people don’t find the “ball of light” when they’re alone with themselves. They try, they dive into themselves, and find darkness there, or a ball of fears, so they hurry back to the surface, back to their ego, which has become a familiar mask with recognisable props and illusions. Katarina, somehow, from various reasons that I hope I managed to show in my novel, never lost the ability to believe there’s goodness at the very bottom of everything, there’s light, the wonder of life. She’ll survive anything, as long as she remembers to dive deep and find her inner strength.

Podgorica features for Katarina as a place where “untold stories” are waiting for her. How important is it to you that these stories from your home city are told – and through fiction – both in Montenegrin and in translation?

I’m so grateful that writing down those untold stories is my calling. I also know it’s my territory. Many writers from my country, convinced that it’s such a small and unimportant country and language, and that the stories from where we are will probably never have a wider audience, turn to trends or whatever topic they think will be safer and sell better. I’ve always believed that the deeper you go into your own experiences, the more universal your writing becomes.

Katarina notes that “all of us lost our country” and that Montenegrins are encouraged to “live the lie” of strength, solidarity and a bright future – what role does fiction have in stripping bare these lies and this loss?

It’s all true, the loss, the lie… Montenegro has this magic-like name, it had some stunningly heroic moments in history, and it’s a beautiful country, as if nature wanted to display, in a small space, the samples of all that she can do and say “Voila!” This is enough of pure praise from me. I don’t work for a tourist agency. In my mind’s eye, there is the image of my country chained onto a floating device and left in the rough sea to be saved only by luck. But many societies in the world are still closed, manipulative and patriarchal, and they all prefer tourist guides or pamphlet-like writing to the kind of fiction that is able to make fun of their see-through propaganda, to defy the authorities and refuse to be on their payroll.

Coming next week:

“I’ve never read another book that celebrates a woman’s individuality the way this book does.”

“My approach has been to trust the reader’s acuity and not talk down or simplify a book for an imagined ignorance.”

Interview with Paula Gordon and Ellen Elias-Bursać, translators of Catherine the Great and the Small