Facing a human-induced environmental crisis (Braidotti, 2013), political and economic instability and injustice (Stein et al. 2017), and a growing neoliberalisation of education (Harris, 2005) this experiment tried to challenge these issues by questioning the space of education through the lens of choreography.

How can the tools of ‘expanded ’choreography be situated within the milieu of the pedagogic act?” This question drove the research of the participatory choreographic project “The Nomadic School of Moving Thought” in 2020. The project explored the intersections between unconventional choreographic tools and pedagogy, aiming at shifting learning from being mind- centered to ‘bodying’-centered by exposing the importance of the multiplicity of the relational body within the learning process.

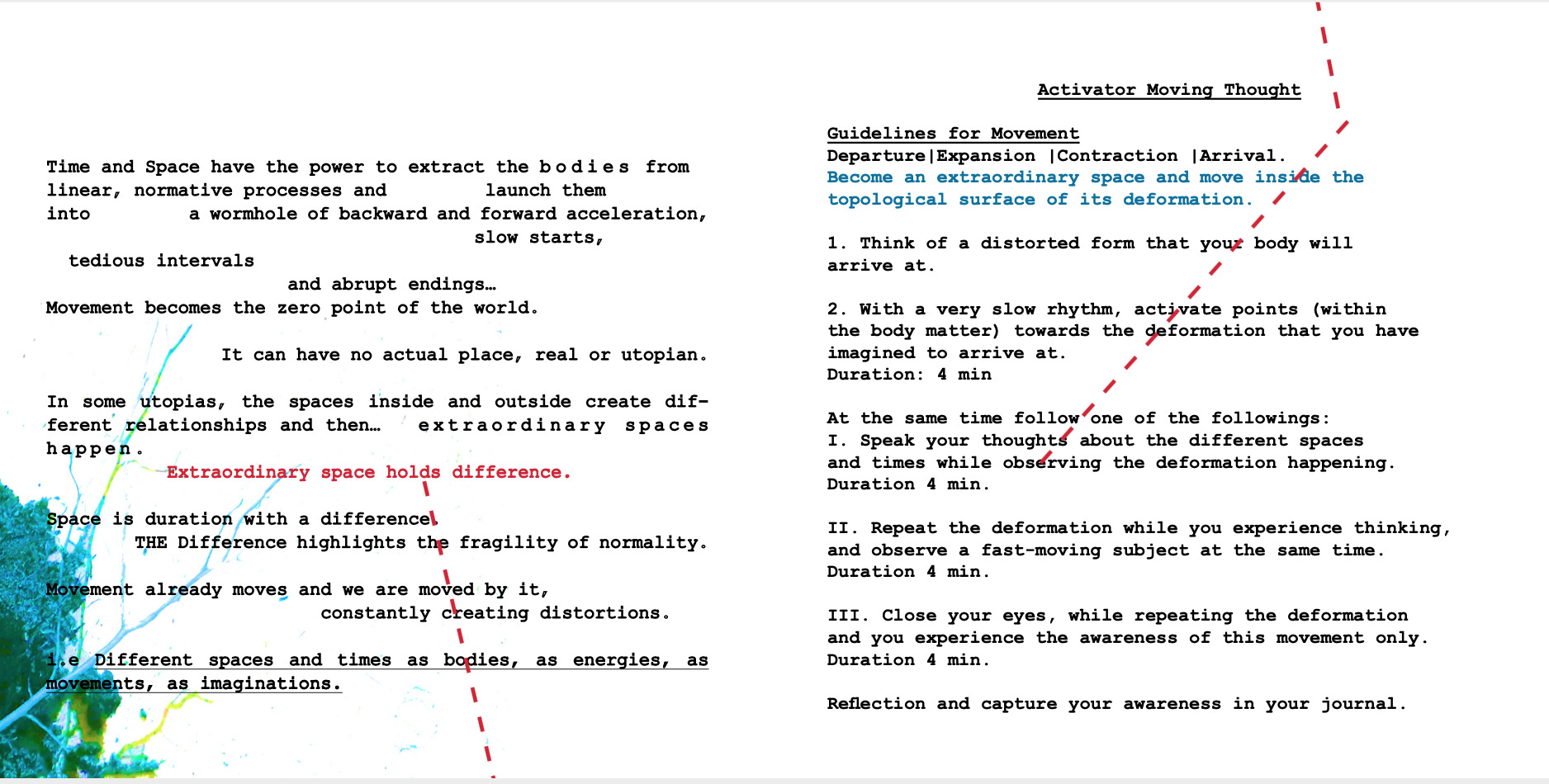

“The Nomadic School of Moving Thought” is conceived as an ‘expanded ’choreographic space that contains different locations and performative activations with the purpose to activate the moving thought and create affective performative spaces. It is a rhizomatic book of suggested choreographic compositions and it applies materialistic attention to the embodiment (Ulmer, 2015) and supports ‘bodying ’(Manning, 2012) as the action of continuously forming a body.

The book explores critical ways of practicing and composing inter-relational encounters in everyday life, beyond the dance field. It unfolds a performative movement education oriented towards an alternative understanding of thinking and raises questions towards sensorial and affective dimensions of being in the current era.

The research took multiple directions on ‘making, attending, performing’ (Cvejić, 2017: 24) for both learners and the dance practitioner following a rhizomatic approach (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987). Rhizome has been used as a method to deform habits of thought, and as a tool to entwine things together and create a dynamic multilayered constellation, by not following a linear structure.

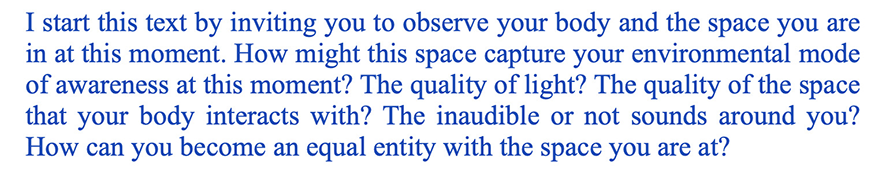

Extract from the book“ The Nomadic School of Moving Thought”

‘Expanded’ choreography introduces a more broaden understanding of choreography and movement and opens up possibilities as to where and with whom choreography can exist. It activates relationality and conjunctions and it entails a more than human ontological intention. ‘Expanded ’choreography (Cvejić, 2015/ Ingvartsen, 2016/ Ölme, 2017) has been used as a creative imaginary milieu of the articulation of concepts, questions, actions, aesthetics and philosophical thinking. It allows the activation of movement and non-movement, includes human and non- human elements, and develops the manifestation of performative ideas under a contingent creative and critical thinking process.

For the composition of the choreographic practices I have applied two concepts: materialistic attention to the notion of embodiment and ‘bodying’. Barad (2003) refers to ‘embodiment as a matter not of being specifically situated in the world, but rather of being in the world in its dynamic specificity’ (Barad in Ulmer, 2015: 39). Manning, trying to rediscover values in the learning process, materializes the concept of how thought moves independent of the human subject. “…thought is not first in the mind. It is in the bodying… In the ecology of practices… of how thought moves, how it moves us, and how it moves the world” (Manning, 2015: 208). So ‘bodying’ (Manning, 2012) is the action of continuously forming a body.

Materialistic attention to the notion of embodiment can acknowledge that, movement knowledge is not only produced within the human, and also can recognize learning as an embodied, affective, relational understanding (while emphasizing the complex materiality of bodies immersed in social relations of power).

Based on this understanding the practices of the book propose:

- to be attentive in ‘bodying ’in various situations

- to acknowledge thoughts as equal parts of the body activity and re-identifying learning through the whole body

- the idea of an ecological body as a way of constantly becoming and creating knowledge

The pedagogic act in this project was focusing on activating emancipatory potentials between humans. Affirming uncertainties, risks and possibilities within the communication (Biesta, 2004) I applied what Rogoff mentions in the academy as ‘potentiality, actualization and access (Rogoff, 2006). Learners were situated as active creators in the teaching-learning process, which permitted diverse learning processes to occur without predicting the end of the process. This offered a more democratic perspective of participation.

In addition to the concepts of equality, democracy, emancipation, and politics (Biesta, 2004/ Rancière, 2009) between humans, I tried to create spaces to think differently about ourselves (Braidotti, 2018), and the effect of the non-human in the knowledge production system.

Educators from different disciplines of art and science as well as movements, nature, objects, senses, bodies, time, and concepts were the participatory body in this research for two months. Participants shared their critical embodied imagination and different qualities of knowledge generously, with a sensorial emphasis, acknowledging that we may affect matter and that matter also affects us.

Expanded choreography became a method of an open-ended choreo-thinking to set into action the relational learning of the participants as it exposed:

1. The sensorial bodying as a dynamic way of learning

2. Choreography as a very complex, dynamic, pedagogic and socio-material entangled tool that can be transformative and emancipatory for the participants (learners and teachers).

3. Potentiality to infiltrate political, economic and cultural structures for a more sustainable future, raising questions towards sensorial and affective dimensions of being in the current era.

Following a materially informed post-qualitative methodology (MacLure, 2013/ St. Pierre, 1997) the research captured the moving relationship between discursive practices, imagination and material phenomena. The creative analytical process revealed three affective performative spaces. These ‘spaces ’allow the contingent and dynamic relationship between the discursive and the non-discursive, the linguistic and the material, bodies and movement, the epistemological and the ontological, the participants and the readers to disrupt, interrupt, negotiate, negate and co- exist. These are spaces that bring attention to the non-linguistic nature of knowledge that exists within a movement-informed creative learning process and the entwined relationship between humans and non-humans in it. They illustrate the intersection between pedagogy and expanded choreography while keeping data alive (MacLure, 2013: 229).

Fusing participants’ temporalities into a spatial form, offered me a space to imagine a conceptualization of temporality itself; temporalities that “irrupt” (St. Pierre, 1997) into sensations and unfold choreographic spaces. Participants shared choreographic attentive ‘planetary dimensions’ (Braidotti, 2014), and their collective temporality brought a new world.This map below is an assemblage of “heterogeneous components or forces…” (Feely, 2019: 6). It is composed as a ‘space of discourse, fantasy and corporeality ’(Massey, 1999) assembling different material of the participants, driven by wonder (MacLure, 2013) and invites the reader by ‘Departing, Traveling and Arriving’ to bring multiple belongings into the context and generate new temporalities (St. Pierre, 1997).

Digesting this process, expanded choreography in this project can be seen as a dynamic political apparatus to change the way human participants understand ‘the learning body as part of the whole ’(Barad in Ulmer, 2015) and re-evaluate the basic principles of our interactions with nature in times of this urgent ecological crisis (Braidotti, 2013/ 2018).

Due to the pandemic of 2020, the project started with a need for mutation and the actualization of it, took an individualistic focus. The participants never met. They worked individually in their own time and space around Europe. Pierre Bourdieu (1998) refers to mindfulness practices as a structure of learning to turn away from civic responsibility and the cultivation of collective mindfulness.

As the project aimed for collective learning, “The Nomadic School of Moving Thought” keeps on being shared. It continues to embrace uncertainties and permit changes and different ways of activation with its main core suggesting the body as a collective ontological space that functions with care for equal relationships in the world. Please visit this website for further information: https://unpluggeddance.com/workshops-posts/workshop-1.

Photo: @unpluggeddance

References:

Barad, K. (2003) Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter, Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society (28)3, pp.801-831 DOI:10.1086/345321

Biesta, G. (2004) Mind the Gap!” Communication and the Educational Relation. In C. Bingham & A. Sidorkin (Eds.), Counterpoints, Vol. 259,No Education without Relation, Peter Lang, pp.11- 22

Bourdieu, P. (1990) The Logic of Practice (R. Nice, Trans.). Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Braidotti, R. (2013) The Posthuman. Oxford: Polity Press, pp.1-55/ 186-197

Braidotti, R. (2014) Lecture: Thinking as a Nomadic Subject, https://www.ici- berlin.org/events/rosi-braidotti/

Braidotti, R. (2018) A Theoretical Framework for the Critical Posthumanities. Theory, Culture & Society. Transversal Posthumanities 0(0). sagepub.co.uk/journalsPermissions.nav, pp.1–31.

DOI: 10.1177/0263276418771486

Cvejić, B. (2015) From Odd Encounters to a Prospective Confluence: Dance-Philosophy. Performance Philosophy 1 (1):7-23.

Cvejic, B. (2017) Problem as a Choreographic and Philosophical Kind of Thought. In: The Oxford Handbook of Dance and Politics, [Ed] Rebekah J. Kowal, Gerald Siegmund, and Randy Martin, DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199928187.013.4

Deleuze, G. & Guattari, F. (2005 [1987]) A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. (B. Massumi, Trans.). New York & London: Continuum, pp. 3-25

Feely, M (2019).Assemblage analysis: an experimental new-materialist method for analysing narrative data. Qualitative Research. 20. 146879411983064. 10.1177/1468794119830641.

Harris, S. (2005) Rethinking academic identities in neo-liberal times. Teaching in Higher Education: Critical Perspectives, 10(4), pp. 421-433. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/ 10.1080/13562510500238986

Ingvartsen, M. (2016) EXPANDED CHOREOGRAPHY: Shifting the agency of movement in The Artificial Nature Project and 69 positions

M a c L u r e M . ( 2 0 1 3 ) R e s e a r c h i n g w i t h o u t representation? Language and materiality in post- qualitative methodology, International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, (26)6, pp.658- 667. DOI: 10.1080/09518398.2013.788755

MacLure, M. (2013) The Wonder of Data. Cultural Studies-Critical Methodologies, 13(4), pp. 228-232, DOI: 10.1177/1532708613487863

Manning, E. (2012) Relationscapes. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, pp.1-5

Manning, E. (2015) 10 Propositions for a Radical Pedagogy, or How To Rethink Value. Inflexions 8, Radical Pedagogies, pp.202-210. http://www.inflexions.org/radicalpedagogy/PDF/Manning.pdf

Massey, D. & Allen, J. & Sarre, P., (1999) Human Geography Today. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, pp.243-323

Ölme, R. (2017) Movement material – A materialist approach to dance and choreography”. Journal for Research in Arts and Sports Education, Special Issue: “Å forske med kunsten” Vol. 1, 2017, pp.95–111. http://dx.doi.org/10.23865/jased.v1.967

Rancière, J. (2009) The Emancipated Spectator. London: Verso, pp.1-13 Rogoff, I. (2006) Academy as Potentiality. In: A.C.A.D.E.M.Y. Revolver.https://www.raggeduniversity.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/ 2017/12/Rogoff-academy-as-Potentiality.pdf

St. Pierre, E. A. (1997) Methodology in the fold and the irruption of transgressive data, International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, (10)2, pp.175-189, DOI:10.1080/095183997237278

Stein, S., & Hunt, D. & Suša, R. & de Oliveira Andreotti, V. (2017) The educational challenge of unraveling the fantasies of ontological security. Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education, 11(2), pp.69-79

Ulmer J. B. (2015) Embodied writing: choreographic composition as methodology, Research in Dance E d u c a t i o n , ( 1 6 ) 1 , p p . 3 3 – 5 0 , D O I : 10.1080/14647893.2014.971230

The light bulb is a symbol of knowledge and thought. The glass enclosure represents the education system and its boundaries. One boundary that challenges me is education and teaching’s non-neutrality and that I might unconsciously exclude children who do not share my ways of being as a middle class, white, settler-Canadian. The light bulb is my own space as an object/relation model. But the boundaries should not be solely determined by me – a relational space creates an environment for students’ identities and knowledges in a way that fosters agency and relationships. With this in mind, the globe of the bulb is breaking to symbolise the disruption of my own Eurocentric norms. This is a reflection of my developing openness and understanding of more holistic approaches to learning. The honeybee trapped in the bulb symbolises personal power and community. I have come to learn that power will be in all relationships and therefore will be present in my teaching. I am learning to recognise that I can use power positively to equalise relationships in the classroom through co-constructing meaning with and through my students’ funds of knowledge. Likewise, the roots symbolise my own networks of funds of knowledge, but also serve as a reminder to delve deeper when connecting to others. Lastly the colour scheme I have chosen is shades of yellow, black, grey, brown and a hint of blue. Yellow represents my own enlightenment as I develop an awareness of this new knowledge; the darker shades symbolise the tendency to understand differences as distinctions.

The light bulb is a symbol of knowledge and thought. The glass enclosure represents the education system and its boundaries. One boundary that challenges me is education and teaching’s non-neutrality and that I might unconsciously exclude children who do not share my ways of being as a middle class, white, settler-Canadian. The light bulb is my own space as an object/relation model. But the boundaries should not be solely determined by me – a relational space creates an environment for students’ identities and knowledges in a way that fosters agency and relationships. With this in mind, the globe of the bulb is breaking to symbolise the disruption of my own Eurocentric norms. This is a reflection of my developing openness and understanding of more holistic approaches to learning. The honeybee trapped in the bulb symbolises personal power and community. I have come to learn that power will be in all relationships and therefore will be present in my teaching. I am learning to recognise that I can use power positively to equalise relationships in the classroom through co-constructing meaning with and through my students’ funds of knowledge. Likewise, the roots symbolise my own networks of funds of knowledge, but also serve as a reminder to delve deeper when connecting to others. Lastly the colour scheme I have chosen is shades of yellow, black, grey, brown and a hint of blue. Yellow represents my own enlightenment as I develop an awareness of this new knowledge; the darker shades symbolise the tendency to understand differences as distinctions.  The light bulb remains a symbol of knowledge and my learning in this course and throughout life. It is now illuminated with a bright white light that shines through the translucent paper representing the process of my teacher beliefs and ways of being and doing expanding to include more holistic approaches to learning. It continues to represent the education system and its boundaries and the bulb continues to break but does not shatter because my privileges and norms may continue to be unintentionally concealed from me. The translucent paper illustrated the disruption of my Eurocentric norms and the use of my own identity to start incorporating relational and decolonial pedagogies in my everyday teaching. The honeybee is still trapped but its new position symbolises my longing to share power with the students rather than using my power to unknowingly silence my students’ voices. I recognise that power will be present in all relationships and that I can have a role in sharing and distributing this power. With this in mind, flowers have blossomed from the roots in my drawing. This network of plant growth symbolises my own funds of knowledge and how they might connect to students’ funds of knowledge. The splotches of colour that surround the light bulb represent what it means to be literate – not simply the ability to read and write, but also environmental, racial, emotional, technological and many more literacies. Lastly, critical literacy is a social practice; it is part of our everyday lives as we “read” the world around us. I want to challenge myself to act on these new understandings and to be more successful in developing meaningful learning experiences that evoke engaged responses from my students.

The light bulb remains a symbol of knowledge and my learning in this course and throughout life. It is now illuminated with a bright white light that shines through the translucent paper representing the process of my teacher beliefs and ways of being and doing expanding to include more holistic approaches to learning. It continues to represent the education system and its boundaries and the bulb continues to break but does not shatter because my privileges and norms may continue to be unintentionally concealed from me. The translucent paper illustrated the disruption of my Eurocentric norms and the use of my own identity to start incorporating relational and decolonial pedagogies in my everyday teaching. The honeybee is still trapped but its new position symbolises my longing to share power with the students rather than using my power to unknowingly silence my students’ voices. I recognise that power will be present in all relationships and that I can have a role in sharing and distributing this power. With this in mind, flowers have blossomed from the roots in my drawing. This network of plant growth symbolises my own funds of knowledge and how they might connect to students’ funds of knowledge. The splotches of colour that surround the light bulb represent what it means to be literate – not simply the ability to read and write, but also environmental, racial, emotional, technological and many more literacies. Lastly, critical literacy is a social practice; it is part of our everyday lives as we “read” the world around us. I want to challenge myself to act on these new understandings and to be more successful in developing meaningful learning experiences that evoke engaged responses from my students.