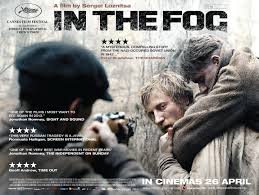

Our next Screen Talks event will be on Monday 17th November, 6.00pm at Exeter Picturehouse. Dr Muireann Maguire, Lecturer in Russian, Dept of Modern Languages at the University of Exeter) will introduce In the Fog (Sergey Loznitsa, 2012).

Join the event on Facebook and find out more here.

Booking Information: Book online, call the Box Office 0871 902 5730 or buy tickets on the door (half price for students on Mondays).

Muireann has written a guest-blog post for us on the film:

‘On a cold, slushy day in the autumn of the second year of the war, the Partisan scout Burov was riding to Mostishche station so as to shoot a traitor – a peasant from those parts with the surname Sushchenya’. Thus begins the Belorussian writer Vasil Bykov’s novella In The Fog (1989), adapted in 2012 as a film of the same name by the director Sergei Loznitsa. Loznitsa’s version follows Bykov’s story with scrupulous accuracy almost to the very end. The setting is Belorussia (modern Belarus) in 1942; the Wehrmacht have pushed as far as the Volga in the East and Leningrad in the North; all of Western Russia, Ukraine and the Baltic states are under German occupation. The Germans have effortlessly assimilated existing Soviet administration and infrastructure, installing German garrisons in major towns and enforcing martial law. With the Red Army fighting a desperate rearguard action far to the east, the only local resistance is coordinated by small bands of partisans surviving in the forest. If a man betrays his comrades to the Germans, the partisans ensure that he is shot. Simple logic, apparently. And yet, in Loznitsa’s elegant and surprisingly sensuous adaptation, this story becomes anything but simple.

Sergei Loznitsa belongs to a generation of directors born in the former Soviet Union (including Fyodor Bondarchuk, Aleksei Popogrebsky and Andrei Zvyaginstsev) whose work engages directly with the increasingly nationally relevant – and politically fraught – field of Soviet history. As cultural memory has moved to the forefront of ideological debate, it suffers increasing state manipulation. Putin’s government has tightened controls over the teaching of history in schools (by commissioning a new national textbook that will omit, among other things, the facts about Stalin’s collusion with Hitler in 1939, and about liberal opposition to Putin’s regime since 2000) and on how records of Soviet-era repression are kept (a disregard for historians demonstrated by the 2013 police raid on the Moscow office of the human rights charity Memorial). In this context of centralized obfuscation and explicit state dishonesty, directors like Loznitsa and Popogrebsky have developed a new aesthetic that aims, as the film scholar Vladimir Padunov suggests, to expose untruth by showing rather than by telling. Both directors choose individual or local situations that metonymically represent larger themes of transformation or suffering; the narratives typically rely on close-ups, extended takes, and out-of-sequence flashbacks rather than dialogue or action; and they favour forms such as the road movie (Loznitsa’s My Joy (2010); Zvyagintsev’s The Return (2003)), the coming-of-age drama (Popogrebsky’s How I Ended This Summer (2010)), and especially for Loznitsa, the documentary. Almost all his films are documentaries, and even those which venture outside this genre – such as In The Fog and My Joy – display documentary skills, particularly their combination of fine visual detail with historical accuracy. In an interview for Russian Cinema [in Russian], Loznitsa stated that his main aim as a director is to ‘show the absurdity of what is happening’ in the world, on-screen.

Loznitsa’s path to directing was unconventional. Born in Belarus in 1964, he later moved to Kiev, where he studied engineering and mathematics; he then researched artificial intelligence at Russia’s Institute of Cybernetics while working part-time as a Japanese-Russian translator. In 1991 he enrolled at the VGIK, the Russian State Institute of Cinematography, to train as a director. While Loznitsa’s very first film, the 1996 documentary Today We Are Going To Build A House, won prizes abroad, it was the 2005 Blockade that secured his international reputation. Blockade, which describes the 900-day siege of Leningrad during the Second World War, was Loznitsa’s first venture into the subgenre that Padunov calls the ‘compilation film’. Blockade consists of newsreel footage, sometimes including original voiceovers, re-edited and combined into a sequence which conveys both the stringency of life during the siege, and the often ludicrous and futile character of contemporary propaganda. Loznitsa has continued to elaborate his own versions of both compilation and more conventional documentary films: his latest, Maidan (2014), uses footage from a fixed camera overlooking Kiev’s Independence Square to depict crowd action and public speeches during Ukraine’s anti-government protests in late 2013 and early 2014. Loznitsa emphasizes the importance of studying the past: ‘History which has not been understood, or fully comprehended, or reflected upon, continues to live with us and within us, presenting itself over and over […]’, he concluded that same Russian Cinema interview. As Jeremy Hicks argues persuasively in his review of Loznitsa’s 2008 documentary Revue, the director also intends to provoke speculation about the constructed nature of any documentary by ‘lay[ing] bare the process of representation’ and performance. In The Fog incorporates and arguably transcends this speculation.

The film opens with the execution of three local railway workers by German troops in a scene that compellingly subverts audience expectations of revelation: we never see the victims directly. Instead, we watch the expressions on the faces of locals as the camera pans impassively over a crowd scene; we hear the indictment read aloud as soldiers sit idly by; and as the camera settles on a heap of human remains, we hear the gallows doing their work. This grim scene presages the wealth of unexpectedly sensuous detail – the colour of individual leaves, the detail on an embroidered nightdress, the texture of snow or fog – which fills in the film’s otherwise claustrophobic focus on its three main characters’ wanderings. (This deliberately circumscribed diegesis helps to distance Loznitsa’s film from the other major Russian feature film set in Belorussia during the war, Elem Klimov’s 1985 Come and See, with its greater narrative complexity and more numerous cast). As a consequence of these executions, two partisans – Burov and his shifty sidekick, Voitik – track down Sushchenya, a railway worker who was mysteriously spared by the Germans when his comrades were killed. Both partisans and, indeed, all the villagers, with the possible exception of Sushchenya’s wife, assume that Sushchenya betrayed his comrades by implicating them in sabotage. With only one explanation, there can only be one outcome. Sushchenya, accepting his fate after only a mild protest of innocence, allows the partisans to take him deep into the forest, where he digs his own grave. At the last moment, Burov is wounded in a police ambush; Voitik flees, but Sushchenya returns to carry his old friend and would-be executioner to safety. As Voitik, Burov and Sushchenya struggle through the thick, emblematically Russian forest, there is no guarantee that innocence will be heard or, if heard, believed. As Sushchenya says plaintively, he used to be well-regarded in his community. Why did everyone turn against him? His question transcends the context of the war or Sushchenya’s own troubles, to interrogate the construction of identity and the frailty of trust.

Voitik’s and Burov’s identities are also questioned in a sequence of flashbacks: as Denise Youngblood points out in her review, both are accidental patriots, forced to join the partisans by chance rather than conviction. Who is responsible for this tragic narrative of confusion and deception? It would be easy to blame the Germans, whose strategy of implicating Sushchenya by default is analogous to their wider policy of imposing a mutually inimical binary of collaboration and resistance on the nations they conquer: this is what Peter Bradshaw’s review insightfully calls ‘a secret and exquisitely cruel perquisite of victory: sadistically imposing self-hate on the defeated ones, renewing the triumph by perpetuating the conquered people’s division and dismay’. But the film’s title suggests a clue that the ultimate source of confusion may be even more abstruse than Wehrmacht policy. Bykov’s novella ends with a glimpse of a partisan column creeping through the forest, unwittingly bypassing the remains of Sushchenya’s party; Loznitsa’s film replaces this scene with a long take of sinuously billowing, dove-grey, all-concealing fog. The sound track, rather than the camera, tells the end of the story. Loznitsa’s use of fog as narrative punctuation has a major precedent in Russian literature: the Ukrainian writer Nikolai Gogol’s 1836 story The Nose, which twice interrupts its own narrative at particularly incredible points by gleefully manifesting an impenetrable cloud. As Gogol’s narrator claims, ‘But here the story is completely hidden by fog, and what happened afterwards is most definitively not known. […] After that… but here once again the entire story is covered in fog, and what happened then is certainly unknown’. Both Gogol’s and Loznitsa’s fogs revealed more than they concealed. Gogol’s metafictional mist laid bare the cliché of the omniscient narrator, drawing attention to the artificiality and arbitrariness of plot construction; Loznitsa’s all-too-real fog exposes the vulnerability of identity to misconstructions by others, and the tragic failure of speech in a world of signs.

Dr Muireann Maguire lectures in Russian at the University of Exeter; current research interests include nineteenth-century Russian literature, and twenty-first-century film adaptations of Russian science fiction.