CREATOR/S: Sanho Kim with Michael Juliar

YEAR: 1973

PLACE: Southfield, MI

PUBLISHER: Iron Horse Publishing Co.

ORIGINAL PRICE: $1.50

PRINT RUN: Not known

WHERE CAN I READ IT FOR MYSELF? Michigan State University or Ohio State University or Library of Congress

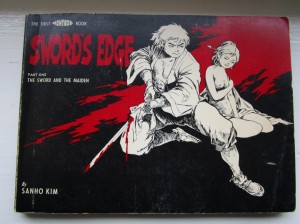

Cover of Sword’s Edge © 1973 Iron Horse Publishing Company, Inc.

It’s a short one this month – the length of this blog, that is, not the text (although at 7½” x 5½” it does have smaller page dimensions than most other books of comics from the 1970s). I am discussing Sanho Kim’s “Montage Book” Sword’s Edge, Part One: The Sword and the Maiden, published in 1973 by the Iron Horse Publishing Company. I don’t believe this press published any other long-form, book-format comics, and neither do I know of any further instalments of the Sword’s Edge saga. Please let me know if I’m wrong! On a similar note I have yet to find much information about this text (e.g. how it came to be published, how it was distributed, the size of the print run or how many copies were sold) and I’d love to have some answers to those questions.

What do I know about Sword’s Edge? According to Lambiek Comiclopedia Kim was born in 1939 in Korea, where he began a career as a comics creator in a variety of genres. He started working for several US comics publishers in the 1960s, and the Grand Comics Database shows him working for Warren, Marvel and others, doing the bulk of his duties on Charlton’s comics: his time on the Cheyenne Kid (beginning in May 1969) stands out. He continued to pencil and ink, and occasionally script, across a spectrum of genres: SF, westerns, war and horror. Sword’s Edge made a tiny splash within fandom – Gil Kane’s paperback Blackmark (1971) was a prized trophy and recurrent point of reference but Sword’s Edge gets barely a mention in the APA mailings, newsletters and fanzines I have consulted. One exception: The Comic Reader noted the publication of Sword’s Edge in its January-February 1974 issue, identifying Kim as an artist at Charlton. It added that this was “the first in a series of sword-fighting adventure-romance stories told in comic book style but in paperback format. The book […] is a departure from the normal American comic fare.” (“Et Al” 2)

On the grounds of content I’m not sure the book is that different “from the normal American comic fare.” The narrative begins with the eighteen-year-old Hyunil Shin travelling to Seoul to compete in the National Swordsman Championships. During the journey Shin encounters bandits, a well-informed old man, an unlikely monk and the seductive maiden of the book’s subtitle. There is a degree of similarity between Sword’s Edge and the texts, including comics, that came out during the martial arts boom of the early 1970s; the television series Kung Fu, for instance, featured David Carradine as a wandering monk and martial artist and began in 1972.(i) But a deeper point of connection between Sword’s Edge and the comics of its era would be the vogue for sword-and-sorcery triggered by the success of Marvel’s Conan the Barbarian title, a series which began in 1970. Shin’s trek involves navigating a series of violent or sexual encounters, meeting characters who hide their true identities only for them to be dramatically revealed later in the narrative (I will try to keep spoilers to a minimum here). In terms of narrative structure and the representation of violence, sex and nudity, Sword’s Edge has much in common with the sword-and-sorcery comics of the 1970s, especially with the more adult, magazine-format sword-and-sorcery comics published later in the decade (a key distinction is that the milieu of Kim’s book is medieval Korea and not an invented fantasy world).

Something interesting is happening with the layouts in Sword’s Edge. With scenes of emotional intensity or dramatic importance Kim is less fixed on using the spatial succession of panels to imply the unfolding of events in the chronological sequence in which they take place. For example the lovemaking scene between Shin and the maiden on page 83 is constituted of nine panels showing bits of bodies and one panel containing an exterior shot of the house. The panels could be read, left-to-right and top-to-bottom, as a chronological sequence, but the kinds of prompts that would make this the obvious preferred reading aren’t available (only one panel contains dialogue and panel progression barely follows the logic of cause-and-effect) and once one starts playing about with possible reading options there are a few different ways to move around the page that are equally plausible. The reader is invited to spend time exploring the relations between the panels, thinking about how they fit together, which seems to be a deliberate ploy given that this is the most sexually explicit episode in the book (bashfulness prevents me elaborating this any further).

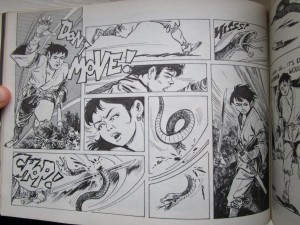

Another key scene is on page 64, when Kim saves the maiden from a snake (see fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Page 64 of Sword’s Edge © 1973 Iron Horse Publishing Company, Inc.

Fig. 1. Page 64 of Sword’s Edge © 1973 Iron Horse Publishing Company, Inc.

Broadly speaking the panels progress chronologically: I venture that many readers will move across the top three panels, left and down to the upper-middle panel of Shin flying towards the snake, down again to the maiden’s shocked face, down once more to the snake getting the “chop!” and then right to the snake being chopped again (give me a moment on that), and finishing with the panel showing Shin with sword in hand. There is some flexibility to making one’s way through the panels: we could read the panels at the top of the middle of the page – Shin’s legs running and Shin’s shoulder, head and wrist in motion – either way round. Taking Shin’s speech out of a speech balloon in the first panel is intriguing: I find the arrangement of the words has the effect of forcing me to pause momentarily over the “DON’T” before plunging down to read the “MOVE,” at the end of which the momentum of my train of sight carries me into the far-right panel with the snake. It all takes place very quickly but my viewing process is arrested by the first word, “DON’T,” and then flung rightwards to the end of the page because I follow the line established by “MOVE!” So. My impression is that those panels at the top of the middle of the page are occurring simultaneously, hence the flexibility in reading them. The panels with the snake being sliced in two seem to operate on the same principle: we are shown the same event in time from different angles. When we see the snake on the ground on page 65 it lies in two pieces, so while it is possible the second panel is Shin’s swiping his blade through the gap made in the already-severed snake the most likely explanation is that this is the same event being visualised in separate panels, or maybe that the second panel shows the displacement of air as Shin follows through with his arc. It’s as if that second panel is a kind of trophy, elongating the emotional apex of the preceding panel by repeating the image. Further, the speed-lines of Shin’s blade, which are roughly aligned at the moment they sever their respective frames, seem to cut each panel in two. This is more obvious in the second panel and it emphasizes Shin’s martial abilities in besting the snake.

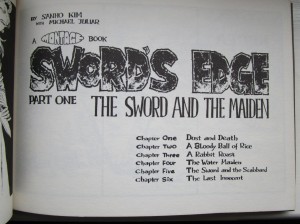

Fig. 2. Contents page of Sword’s Edge © 1973 Iron Horse Publishing Company, Inc.

Fig. 2. Contents page of Sword’s Edge © 1973 Iron Horse Publishing Company, Inc.

Sword’s Edge claims, on its front cover, to be the first example of a “montage book.” Looking at its peritexts (paratexts which are part of the same volume [Genette 4-5]) Sword’s Edge is like many graphic novels of the 1970s:

- the story is divided into chapters (see fig. 2)

- the high quality of the reproduction, binding and paper is emphasized, and with that, the explicit instruction that this is a comic to keep on a bookshelf rather than discard as ephemera

- Sword’s Edge has an introduction from the person responsible for the bulk of the creative tasks

- that introduction extols Sword’s Edge for being unlike other comics and for demonstrating what the potential of the medium could be

- that introduction insists that the creator, after years of working for editors in the US industry, is finally able to pursue a project representing their personal vision

Several graphic novels alluded to the cinema as their source of inspiration and Kim’s notion of montage starts with film too. The reader is given a dictionary-style definition of montage: putting together or assembling. More specifically it means “the cutting and editing of a motion picture.” A montage is “a cinematic sequence of images and sounds which create an idea or feeling in the audience not present in any one image or sound alone.” [9] This is elaborated further in the following pages, which explain the kinds of influences fused together in the book, and the central importance of a harmonious relationship between the entire creative team working towards the same goal. There is an appealing simplicity to calling Sword’s Edge a montage book: it is a book that contains a sequence of images and words and their combination produces certain ideas or feelings in the reader, ideas or feelings that would not emerge from an image or a word on their own. I wonder what Comics Studies would look like if the 1970s had ended with montage book as the preferred term for what we now call graphic novels?

When I think of montage, I think of Sergei Eisenstein. Eisenstein, one of the most important theorists and practitioners of montage in the cinema, saw editing as a contrapuntal process: images might clash with each other, or the sound and image are brought together in jarring tension. Eisenstein is not mentioned by Kim, and observations such as “the artist and the writer must be in harmony” [12] would suggest that contrapuntal use of montage is not what he has in mind for Sword’s Edge, but there are some calculated juxtapositions going on in the text. Take page 33, for example (see fig. 3); by this point in the narrative Hyunil Shin has defeated two bandits in combat (they were trying to steal his last ball of rice). An old man approaches Shin and narrates the skirmish that he saw taking place, and the old man attempts to build a rapport with Shin by describing the swordfight as a particularly robust lesson in etiquette around the dining table.

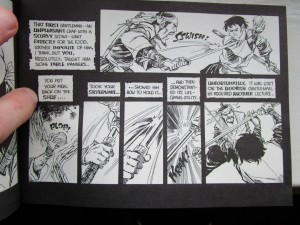

Fig. 3. Page 33 of Sword’s Edge © 1973 Iron Horse Publishing Company, Inc.

Fig. 3. Page 33 of Sword’s Edge © 1973 Iron Horse Publishing Company, Inc.

The incongruity of the old man’s words with the violence of the fighting is witty, but they also serve the purpose of steering the reader to understand what is being shown. In the third panel of the bottom row, for example, it might not be clear that Shin is swinging his sword without the comment that the young warrior was showing the bandit “how to hold it…”

Sword’s Edge was still working within the logic of serial publication: the story ends on a cliff-hanger but no further books in the series appear to have been released. The format and the content were somewhat at odds with each other; the violence, nudity and sexual content put the text in the embryonic adult comics market, despite the peritextual comment “a book for men and women of all ages” [10], but the material text did not resemble a prose novel that an adult might buy. If anything the format evokes books of cartoons or reprints of newspaper strips. This montage book made effective use of strategically ambiguous panel progression and jarring juxtapositions between word and image, but the mismatch between the images and physical format were less well judged, and has perhaps contributed to Sword’s Edge’s obscurity.

Endnotes

i) In the 1970s the films of Bruce Lee quickly gained international popularity and the trend made its way into American comics, including Charlton’s Kung Fu series Yang (the cover date of #1 is November 1973) and various titles at Marvel, with the character Shang-Chi making his first appearance before the end of 1973. In the years after Sword’s Edge was published Sanho Kim contributed to some of the Kung Fu comics, namely Charlton’s House of Yang and Marvel’s The Deadly Hands of Kung Fu.

Bibliography

“Et Al.” The Comic Reader 103 (Jan.-Feb. 1974): 2. Print.

Genette, Gérard. Paratexts: Thresholds of Interpretation. Trans. Jane E. Lewin. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1997. Print.

“Kim San-ho.” Lambiek Comiclopedia. Amsterdam, Lambiek. 8 Aug. 2012. Web. 21 Jan. 2015.