Something different this month: rather than analyse a single text I’m going to reflect on the progress I’ve made on the project since it officially started back in August 2014 (although I’ve been beavering away at it for many years now).

Archival Visits

Since 2011 I’ve visited the following archives/libraries. In an idiosyncratic fashion I’ll say a bit about what I looked at, what you might want to look at, and to make me seem sophisticated, there are some food and drink recommendations for each city (also: I’m in Boston next if anyone wants to suggest where to eat?).

- The University of Texas, Austin (USA)

UT at Austin holds the Jack ‘Jaxon’ Jackson papers: you’ll find a lot of letters (those written to other comix creators and publishers, and a lot of correspondence with historians) and some sketchbooks (containing historical research and layouts for some of his comix).

WHERE TO EAT/DRINK? Manuel’s (a medium-length walk from UT), Vino Vino (a long walk from UT)

- Columbia University, New York City (USA)

Great collection of comics and graphic novels. Columbia has a copy of George Metzger’s Beyond Time and Again from 1976, which is difficult to find elsewhere.

WHERE TO EAT/DRINK? Zabar’s (not very near Columbia though)

- New York Public Library, New York City (USA)

Fan publications including Fanfare and The Comic Reader, the latter on microfilm.

WHERE TO EAT/DRINK? Duke’s, The Ginger Man (within walking distance)

- The Library of Congress, Washington DC (USA)

A massive collection: in the Madison Building you’ll find comics-related stuff spread across the Prints & Photographs Reading Room (where I consulted the Jules Feiffer holdings), the Manuscript Room, the Newspaper & Current Periodical Reading Room, and you can read various early graphic novels in the Main Reading Room in the Jefferson Building (e.g. the four visual novels that Martin Vaughn-James produced in the early-to-mid 1970s).

WHERE TO EAT/DRINK? Eatonville, El Rinconcito Café (neither is near the LoC)

- The Billy Ireland Comics Library & Museum at Ohio State University, Columbus (USA)

Another one where it’s difficult to know where to begin. Apart from the reams of comics and obvious sources like the Will Eisner papers there are many other gems: the recorded interviews in the Arn Saba/ Katherine Collins Papers are a pleasure to listen to, for example. Scholars of fandom will be interested to see the runs of Rocket’s Blast Comicollector and The Buyer’s Guide to Comic Fandom, and if (like me) you want to consult the Fantagraphics issues of The Nostalgia Journal / The Comics Journal that aren’t available on the Alexander Street database for underground and alternative comics, this is the place. And there are permanent and temporary exhibitions upstairs in the galleries.

WHERE TO EAT/DRINK? Northstar Café, North High Brewing, Seventh Son Brewing Company, Barley’s Brewing Company, Blue Danube (all walking distance but some much closer than others)

- Michigan State University, East Lansing (USA)

And one more big archive that holds so many great resources you won’t believe your eyes. What I consider to be the crown jewel in MSU’s holdings is the Eclipse archive, boxes and boxes of art, advertisements, flyers, letters, contracts, all relating to the comics publisher Eclipse Enterprises (later Eclipse Comics). If there are any prospective PhD students thinking about writing a thesis on the comics industry from the late 1970s to the mid-1990s I would visit MSU, since Eclipse gives you a lot of different angles to work with: the creators’ rights movement, the importance of revisionist superheroes for the independent companies, the publication of manga in the 1980s, the use of British creators… if I had a time machine I’d travel back in time and give my 22-year-old self a plane ticket to East Lansing (and some strong advice about dress sense).

WHERE TO EAT? Finley’s (this is in Lansing, MI so not very near MSU)

- Penguin Group Archive, University of Bristol, Bristol (UK)

I consulted materials relating to Raymond Briggs’s books of comics and found some interesting bits and pieces but no scripts / drafts / original art. I got the sense that if you work on illustrated children’s books you’ll find a lot in this archive; also, if you want to do research into the political economy of British book publishing during the 1970s and early 1980s (and the relationship with the US book trade), this would be your destination of choice. Be aware that you need to plan your visit well in advance (you need written permission from Penguin before you can make an appointment to visit) and when I visited in spring 2014 it wasn’t possible to have your laptop permanently plugged in while you consulted the Penguin materials.

WHERE TO EAT/DRINK? The Barley Mow (nowhere near the University of Bristol but quite near Bristol Temple Meads train station)

- The National Art Library at the V&A Museum, London (UK)

The National Art Library wins the prize for the most beautiful reading room I’ve ever visited: high ceilings and book-lined walls and the windows provide views of the V&A’s courtyard. As well as the comics collections it also offers a selection of fan periodicals but not necessarily complete runs. I’ve used the Rakoff Collection (primarily US comic books) and the Andy Roberts Memorial Collection, and I plan to return to the latter for a future project on 1990s British minicomics and the small press (which gives you an idea of what’s in it).

WHERE TO EAT/DRINK? Gordon’s (not near the V&A but easy to get to from there: Gordon’s is just outside Embankment tube station, which is a short tube journey from South Kensington [the stop for the V&A] on Circle and District)

- The British Library, London (UK)

I suppose one expects the BL to have impressive holdings of British graphic novels and comics – which it does – but it also has a terrific collection of American underground comix. These do not always show up by title when searching the catalogue, but if there’s something specific you want to see, put in a request to consult Cup.806.g.1 and write in the ‘Notes’ section of the request the title of the comix you require. If you’re super-keen to know whether a title is in Cup.806.g.1 before you travel to the BL, you can email me and I’ll look at my notes.

WHERE TO EAT/DRINK? King of Falafel, Hare and Tortoise, Chutney’s (all within walking distance and King of Falafel is close enough to go for lunch while you’re working at the BL)

Progress Report

One of the triggers for the project was the gaps I encountered when trying to find out about the history of the graphic novel. I wanted to know – and still want to know – whether Eisner really did popularise the term ‘graphic novel.’ After looking very briefly at copies of FOOM and Mediascene at the National Art Library in 2012 it was obvious that the term was in the air before 1978. And more importantly, I started to realise that if we want to write the history of the novelisation of comics in the 1970s, we’ll have to shake off the fixation with graphic novels alone. Since then I’ve been trawling through fan publications (to date I’ve managed to read extensive runs of Graphic Story World / Wonderworld, Graphic Story Magazine / Fanfare, The Nostalgia Journal / The Comics Journal, Comixscene / Mediascene / Prevue, The Comic Reader, Comix World, Rocket’s Blast Comicollector, The Buyer’s Guide to Comic Fandom and the APA Capa-alpha) and recording when the word ‘novel’ was used to describe a sequential art narrative. I’m closer, now, to answering another question I started with: when creators, publishers and fans talked about comics novels from the mid-1960s up to the end of 1980, what kind of novels were they talking about? Composite novels? Historical romances? Naturalism? How did the use of the word ‘novel’ change over time?

The most difficult task I’ve set myself is to track how comics in book form (particularly, but not only, products explicitly marked as ‘novels’) were produced, distributed and read in the 1970s. The aforementioned fan publications have been extremely valuable in building up the reception history, supplemented by other sources (e.g. letters written to comics creators). Where production and distribution are concerned I’ve been consulting published histories of the comics industry and the book trade, but the finely granulated information I’m pursuing has also sent me to corporate records at the above institutions and the private documents held by publishers active in the 1970s. Some extraordinarily kind and helpful businesses and archives have allowed me to make reasonable progress collecting sales information; right now I have solid figures for around a dozen books of comics from the 1970s (and uncorroborated data for many more).

Which brings me to…

Two Graphs and some comments on Will Eisner

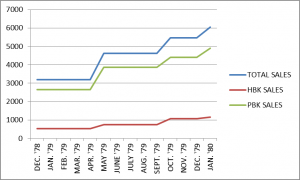

To celebrate Will Eisner week let me share a cumulative sales graph for A Contract with God (1978) from December 1978 to January 1980:

SOURCE: WEE Box 21 Folder 10, Will Eisner Collection, Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH

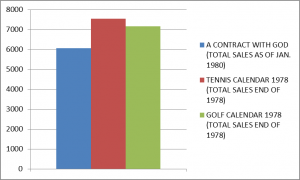

I arrived at these figures by deducting what I take to be the number of returns from the number of initial sales, giving 6059 total sales of A Contract with God by January 1980. This data comes from the Will Eisner papers at the Billy Ireland Comics Library & Museum (WEE Box 21 Folder 10), which also contains sales information on Eisner’s other products from the period. Here is A Contract with God compared to Eisner’s 1978 sports calendars (he drew one about tennis and one about golfing):

SOURCE: WEE Box 21 Folder 10, Will Eisner Collection, Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH

This data comes out of my recent explorations into the reception of A Contract with God. In keynote and visiting lectures I have playfully referred to ‘the Eisner Distortion’ affecting many histories of the graphic novel. The effect of the Eisner Distortion is to pull the 1970s out of shape so that A Contract with God dominates the stage as the first graphic novel. More often these days, it is not identified as the first graphic novel, but cited as the most important early graphic novel – or the one that popularised the term – or the one that changed people’s perceptions of what could be done with complete, long-length comics narratives. I’ve asserted that kind of thing myself in the past. I do think the preoccupation with Contract is slowly changing: Baetens and Frey’s The Graphic Novel: An Introduction (2015), for example, gives an account of the 1970s that resists the tug of the Eisner Distortion’s gravitational force. But I have yet to find a study that assembles evidence from the period to evaluate what kind of importance and influence it is appropriate to attribute to Contract. So I decided to see what I could do myself, which has led to me returning to the 1970s and trying to reconstruct the excitement and uncertainty of the time, when different texts were vying for attention and when graphic novel culture was going through a process of definition that had yet to be settled, when an array of radical possibilities for comics-as-novels was in the air (and being hotly debated within the comics art world).

Looking at communications between fans, as well as reviews in fanzines, the response to Contract was mixed: one group of fans intensely loved it, a smaller group of fans protested that the book’s boosters were wildly over-estimating its importance and innovation, and a lot of readers liked it without any great passion. This latter group didn’t think Contract deserved to be singled out (and some preferred what Eisner had done on The Spirit) but they could appreciate it was part of a general moment of excitement in comics when the long-length sequential art narrative for adult readers was looking like a viable format.

I’m going to try not to use the term ‘the Eisner Distortion’ in future, since what I called the Eisner Distortion is more accurately ‘the Contract with God Distortion.’ One reason why I want to challenge the assumed primacy of Contract is because it obscures and minimises Eisner’s wider contribution to the 1970s graphic novel. Life on Another Planet, serialised in Kitchen Sink’s The Spirit magazine between 1978 and 1980, is far more interesting to my mind, a long and evolving story that addressed a slew of national debates – some of which came to prominence while the narrative was unfolding. My desire to put Life on Another Planet on an equal footing with Contract reflects Eisner’s contemporary evaluation of his serialised graphic novel, his feeling that after Contract he would do something longer and more ambitious and, well, more like a novel.

When I finally get all of this research down on paper Eisner will still loom large as a major figure in the development of the 1970s graphic novel. But he won’t be the only one, and he won’t be represented by A Contract with God alone. If you’ll permit a little more playfulness: serialisation of Life on Another Planet began in issue 19 of The Spirit magazine, cover-dated October 1978, the same month that Contract was officially published. Given that comics traditionally hit the stores before the month shown on the cover, should we call Life on Another Planet Eisner’s first graphic novel?

March 2015