CREATOR/S: Collectively written under the general direction of Larry Wright and A. Mago; art by Chris Welch

YEAR: 1976

PLACE: London

PUBLISHER: Bolivar Publications

ORIGINAL PRICE: £1.00

PRINT RUN: Not known

WHERE CAN I READ IT FOR MYSELF? The British Library

Cover of Introduction to Chile © 1976 Chris Welch and Bolivar Publications

I’m going to suggest – tentatively and acknowledging many exceptions – three dominant trends in the book publication of underground comix:

- First, collections based on popular underground creators (primarily Robert Crumb, Gilbert Shelton, Richard Corben and Vaughn Bodē).

- Second, anthologies usually tied to specific companies (e.g. The Best of the Rip Off Press [Vol. 1, 1973]), periodical series (e.g. The Best of Bijou Funnies [1975]) or specific titles and themes together (The Best of Wimmen’s Comix and Other Comix by Women [1979]).

- Third, educational comix. Sheridan Anderson’s Baron Von Mabel’s Backpacking (1980), for instance, was a pocket-sized book published by Rip Off Press reprinting Anderson’s syndicated strips of backpacking tips. Left-wing histories were prevalent too, and can be divided into subgenres including:

- Revisionist docudrama, such as Comanche Moon (1979) and Los Tejanos (1982) by Jack ‘Jaxon’ Jackson and Give Me Liberty: A Revised History of the American Revolution (1976) by Gilbert Shelton and Ted Richards, with Gary Hallgren and Willy Murphy

- Documentary history, such as Larry Gonick’s The Cartoon History of the Universe, Book One (1980)

The book publication of educational comix is not that surprising, since this was a robust aspect of underground periodical publishing in the 1970s. Periodical comix provided information about reproductive rights (Abortion Eve [1973]), nuclear power (All-Atomic Comics [1976]) and consumerism (Consumer Comix [1975]), as well as histories of anarchism and revolution (Anarchy Comics [1978-87]). Readers interested in finding out more about educational underground comix should check out Leonard Rifas, who has written on the history of educational comics and their use; see his entry on this subject in Booker’s Encyclopedia of Comic Books and Graphic Novels (2010). Furthermore, Rifas was the founder of EduComics in 1976, which published educational comic books, including some of the examples mentioned above.

As with the comix movement more generally, the educational genre was frequently allied to left-wing politics, feminism and other progressive causes. The Mexican creator Eduardo del Rio or ‘Rius,’ perhaps best known for his Marxism for Beginners (first English translation 1976), was a major influence on educational comix, specifically on the work of Larry Gonick (Rifas 166; Petersen 224). Starting in the 1960s Rius “perfected a super-quick style of cartooning (using sketchy drawings and pasted-in found illustrations) which enabled him to research, write, and draw a weekly comic book almost single-handedly.” (Rifas 166) In 1969 Rius created Cuba para principantes (Cuba for Beginners), commemorating the tenth anniversary of the Cuban revolution and its achievements. This historical narrative, composed out of photocopies, caricatures and maps, proved popular on American college campuses in a translated version. Significantly, Cuba for Beginners inserted the revolution into the history of belligerence directed towards Cuba by the USA (Petersen 223). I don’t know whether Chris Welch had read Cuba for Beginners but his 95-page comics narrative Introduction to Chile: A Cartoon History certainly seems to come out of the same left-wing practice of collage and appropriation of images.

Welch was fairly well known in British underground comix circles, contributing to the seminal The Trials of Nasty Tales (1973) alongside creators such as Dave Gibbons. Welch was also the artist on Ogoth and Ugly Boot (1973), written by Chris Rowley and Mick Farren, a 31-page comics narrative (referred to as “a full-length novel” [Burns 9] in 1978). Introduction to Chile details the long history of foreign interference in Chile, moving from the Spanish conquest to nineteenth-century British involvement and finally to the twentieth century and the USA’s substantial influence on the country. The USA offered support to the junta that seized power from President Salvador Allende in 1973. Allende was democratically elected in 1970 and his Popular Unity coalition began a series of reforms to improve the country’s economy, industrial productivity, women’s rights, literacy, access to healthcare and housing. Allende’s socialist experiment was a source of fear and resentment for some members of Chilean society, as well as for the US government. This led to the leaders of Chile’s military declaring martial law and bombing the presidential palace with Allende inside; although the circumstances are unclear, Allende died on 11 Sept. 1973. Chile fell under the rule of General Augusto Pinochet and a period of intense political repression – and economic freefall – began.

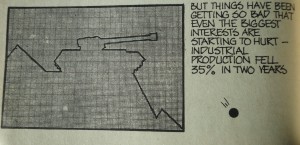

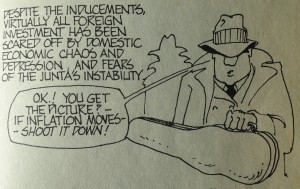

This is the immediate context for Welch’s history, an account of Chile’s last five hundred years that extensively covers the country’s immediate past and present. Welch’s cartooning is smart, succinct and powerful: in an image encapsulating how junta rule has ravaged the economy, with industrial production falling 35% in two years, a tank outline has been inserted into a line graph representing plunging productivity (fig. 1). To conjure up the murderousness of the regime and their inability to manage the economy, Welch pictures the junta’s failed, C.I.A.-influenced economic plan (“administered by the ‘Chicago Boys’”) as a gangster who thinks you can shoot down inflation (fig. 2).

Fig. 1 and 2. Pages [72-73] of Introduction to Chile © 1976 Chris Welch and Bolivar Publications

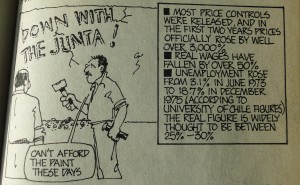

Throughout the book Welch uses two characters painting slogans on a wall as a way of vocalising the hopes and opinions of Chile’s working class. Their clothes change in different historical periods, but these characters – types, really – endure as a symbol of the resilience of the Chilean people. After the junta takes power they are forced to carve their messages because paint has become too expensive (fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Pages [71] of Introduction to Chile © 1976 Chris Welch and Bolivar Publications

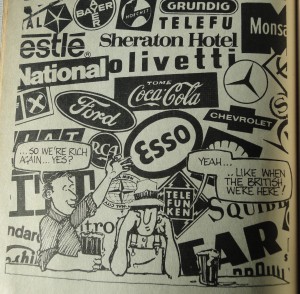

As with the comics of Rius, and fitting a much longer tradition of appropriating found images for radical purposes that includes the interwar German artist John Heartfield, Welch borrows and adapts photographs, logos and paintings, re-contextualising them to tell Chile’s story. The overwhelming foreign control of the Chilean economy in the 1950s is conjured up in a blizzard of corporate brand names dominating a panel with two Chilean men drinking at a bar (fig. 4). As their speech balloons suggest, this twentieth-century foreign investment has brought the same kind of riches that British investment did, i.e. profit that passes out of the country and into the pockets of overseas investors (the book offers an array of statistics to back up this claim).

Fig. 4. Pages [26] of Introduction to Chile © 1976 Chris Welch and Bolivar Publications

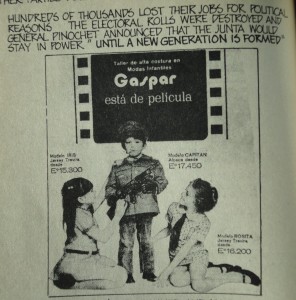

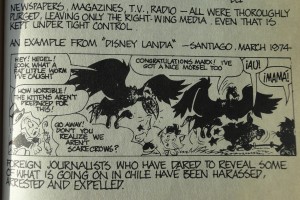

Some images have been reframed but not altered otherwise. They do not need manipulation, since they represent the horrifying evidence of how Chilean society was being remade to ensure maximum allegiance to Pinochet’s new regime, which was reaching into the leisure pursuits of children. Welch includes an advert for children’s outfits that shows a boy dressed in a military uniform wielding a gun (fig. 5), and a panel from March 1974’s Disney Landia, where sinister vultures named Hegel and Marx prey on much cuter animals (fig. 6) (Dorfman and Mattelart clearly not the only leftists ringing alarm bells about the Disney franchise’s adventures in South America).

Fig. 5 and 6. Pages [70], [75] of Introduction to Chile © 1976 Chris Welch and Bolivar Publications

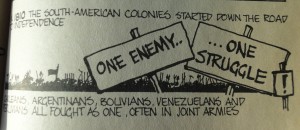

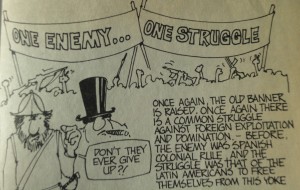

Introduction to Chile ends on a hopeful note, logging the many acts of solidarity committed by British activists mobilising against what was happening in Chile. Chilean refugees were welcomed and supported into UK communities; boycotts of Chilean goods put pressure on the junta; workers at Rolls-Royce factories prevented engines leaving Britain for Chilean Air Force planes. With the phrase “One Enemy… One Struggle” Welch links the South American Wars of Independence (fig. 7) to the 1970s struggle against multinationals, “intelligence agencies, financial bodies, companies, governments and others whose aim is to extract ever greater profits at the expense of the people and keep the system going.” [97] (fig. 8)

Fig. 7 and 8. Pages [13], [97] of Introduction to Chile © 1976 Chris Welch and Bolivar Publications

As that last example indicates, on one level Introduction to Chile is a history in which Chile’s contemporary state is a direct result of the accretion of wealth and power in the hands of a select few. The story’s power comes from this gradual build-up and the reader’s ability to make connections between oppression at different moments in the narrative: American involvement now (i.e. the mid-1970s) stems from that country’s business interests superseding the financial and cultural influence that Britain commanded during the nineteenth century. While the two men painting slogans on Chile’s walls are not so much characters as avatars of proletarian sentiment, it is significant that the opening page of Introduction to Chile frames the following historical narrative as a story told in a British pub (marked as such by the pint glasses and dartboard) by one man to another. As one of them says, what the Chilean people want – a peaceful, legal, constitutional transition to socialism – is “just what we want” [3] too. The symmetry of two left-wing male friends – one pair in Britain, the other Chile – contributing to the story’s telling is a structural expression of the British-Chilean solidarity with which the book ends.

But if the book is looking to manoeuvre allegiance to the socialist cause in Chile through narrative, it is a narrative told through jarring, provocative imagery. Welch is pursuing a difficult task, trying to maintain continuity while arresting one’s attention with striking visuals. I would suggest the artist succeeds in keeping the propulsion of the historical narrative and the atemporal power of the panels in balance, helped by the use of recurring characters and panel compositions (such as the two men in Chile painting the wall or in the bar).

Where toggling between the narrative and the spectacle is concerned, Pinochet and his forces may have a political stranglehold on Chile, but the cover of Introduction to Chile implies that the dictator lacks the visual and verbal literacy to understand what’s happening in the comic. It is almost as if, through sequential art, the left may outfox and undermine the junta’s authority.

April 2015

Bibliography

Burns, Mal. Comix Index: The Directory of Alternative British Graphic Magazines: 1966-1977. London: Media & Graphic Eye Enterprises, 1978. Print.

Dorfman, Ariel, and Armand Mattelart. How to Read Donald Duck: Imperialist Ideology in the Disney Comic. New York: International General, 1975. Print.

Petersen, Robert S. Comics, Manga, and Graphic Novels: A History of Graphic Narratives. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger-ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2011. Print.

Rifas, Leonard. “Educational Comics.” Encyclopedia of Comic Books and Graphic Novels. Ed. M. Keith Booker. Vol 1. Santa Barbara, CA: Greenwood-ABC-CLIO, LLC, 2010. 160-69. Print.