CREATOR/S: Original concept by Kenny Everett, written by Chris Browne, designed and drawn by Roger Wade Walker, lettering by Chris Welch

YEAR: 1977

PLACE: London

PUBLISHER: Corgi Books

ORIGINAL PRICE: £1.50

PRINT RUN: Not known

WHERE CAN I READ IT FOR MYSELF? The British Library

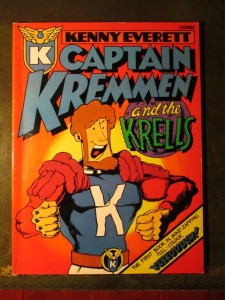

Fig. 1 and 2. Cover and spine of Captain Kremmen and the Krells © 1977 Everex Marketing Company

For my generation, memories of the comedian and broadcaster Kenny Everett start with his appearance at a rally for the Young Conservatives in 1983, and his giant-foam-gloved exhortation “Let’s bomb Russia!” Everett (1944-1995) specialised in a fast-paced, wacky, risqué brand of comedy. As his notorious joke in 1983 indicates, his humour frequently pushed the boundaries of taste. Everett’s antics were reported with horror in the national press, but this did not stop him rising to fame in the 1960s and enjoying a highly successful broadcasting career on radio and television up to the mid-1990s. Hogg and Sellers’s 2013 biography of Everett starts with the “Let’s bomb Russia!” exclamation; this scene is held back until the second page of Andrew Marshall’s foreword to the Everett book by David and Caroline Stafford (also published in 2013). Both biographies resist the idea of Everett as a good Conservative party supporter, emphasising his iconoclasm and his willingness to outrage good taste across the political spectrum. Everett was happy to make the Conservative Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher the butt of his controversial jokes too; apparently Everett could not stand Thatcher, even if he did lean to the right politically (Hogg and Sellers 9, 284: Stafford and Stafford 197-201).

I haven’t done with politics completely, but for the time being let’s turn to the 1977 book Captain Kremmen and the Krells, based on one of Everett’s comic creations. Over a 62-page sequential art narrative we follow the titular character from boyhood to Kremmen’s first mission in charge of the intergalactic vessel Troll 1. The majority of the book depicts the hero’s adventure to save the city of Liverpool from destruction by the Krells, and even after defeating these alien invaders our hero has a further quest to fulfil, regaining command of Troll 1 following an attempted coup. What makes Captain Kremmen and the Krells especially worth one’s attention is that, as I write this in 2015, it appears to be an early example of the British underground graphic novel. This may seem an unusual suggestion since Captain Kremmen and the Krells was issued as a 10¾” x 8” paperback by trade publisher Corgi Books, an imprint of Transworld Publishers, but consideration of the book’s history and the text itself will hopefully bear out my contention.

According to DJ Dave Cash the Captain Kremmen character came to life in the summer of 1965 when he and Everett co-hosted a show on pirate radio.[i] Cash recounts that Kremmen appeared on The Kenny & Cash Show for about three months, but perhaps only for a few seconds at a time. Kremmen became a substantial part of Everett’s radio shows in 1976, when Everett used the space-travelling hero as the main character in a regular science fiction-comedy serial. This serial, full of puns and innuendo, appeared in Everett’s broadcasts for the London-based station Capital Radio.[ii] Everett made recurring use of flamboyant comic characters and the Captain Kremmen serial was a pastiche of the science fiction texts of the comedian’s youth. The aliens named in the title of Captain Kremmen and the Krells allude to the Krell from the 1956 American film Forbidden Planet. Everett had been a devotee of Saturday morning cinema serials (his favourite was Flash Gordon) and The Adventures of Dan Dare radio show, based on the strip from the British Eagle comic (Hogg and Sellers 21, 24). When Everett appeared on BBC Radio 4’s Desert Island Discs, a programme on which public figures choose items for a sojourn on a desert island, he selected an Eagle annual as the book he would like to take with him (Stafford and Stafford 154).

Kremmen proved highly popular with fans in the second half of the 1970s, spawning a torrent of merchandise: an LP record of episodes, watches, T-shirts, patches, badges, key rings, dolls and a Captain Kremmen single. The character starred in a comic strip in a London newspaper and a series of cartoons were created by Manchester-based animators Cosgrove Hall for the Kenny Everett Video Show. This was Everett’s live music and comedy sketch show, which first appeared on Britain’s television screens in 1978 (Hogg and Sellers 233-38; Stafford and Stafford 167). Kremmen: The Movie was released in July 1980 but due to financial constraints it was only 25 minutes long and was exhibited as the B-feature to the Village People’s film Can’t Stop the Music (Hogg and Sellers 240-43; Stafford and Stafford 178-79).

The franchise had a transatlantic reach, even if Everett made very little money from all this merchandising activity: the Captain Kremmen radio serial was syndicated in the USA (Hogg and Sellers 235, 243) and Captain Kremmen and the Krells was advertised in the December 1977 issue of The Comics Journal. The advert’s explanation of the character’s provenance suggests that the British dealer did not take it for granted that readers would be familiar with him: “Captain Kremmen’s adventures are related by Kenny Everett every Saturday on Capital Radio, but, thought Corgi, why should London be the only town to suffer[?]” (Campbell 50). It seems appropriate that this character partly inspired by American science fiction should journey across the Atlantic, although the everyday details of 1970s Britain keep peeping out from behind Captain Kremmen and the Krells’s futuristic setting. The rubbish bins have “KEEP TROLL ONE TIDY” on them, mimicking the Keep Britain Tidy slogan of the period, and the Krells intend to destroy Liverpool on their way to a holiday in Blackpool, a seaside resort in north-west England. After the aliens have been successfully defeated, Kremmen’s starship flies into the London Astroport, “where only the Customs men are allowed to go on strike,” a reference to the industrial action taken by British Air Traffic Control Assistants in 1977.[iii]

So the immediate context for Captain Kremmen and the Krells’s publication is the strong commercial prospect for tie-in material related to Everett’s radio and television shows. The comedian’s name sits across the book’s title on the front cover and on the title page – the credits for the book’s actual creators are tucked away in the indicia. Yet, in translating Everett’s radio character into comics form, the creators of Captain Kremmen and the Krells produced a text with striking similarities to the underground comix movement, both in the UK and the USA. The book’s letterer Chris Welch was one of the better-known underground creators in Britain at the time, and I discussed his Introduction to Chile: A Cartoon History (1976) (a left-wing graphic history) in an earlier blogpost. The background of artist Roger Wade Walker was in illustration but he did occasional uncredited work for Fleetway’s aerial warfare comic Air Ace Picture Library in the early 1960s. Walker was included in the project because of his friendship with Everett; as the comedian’s neighbour the artist had spent time in Everett’s home studio and observed him recording the Kremmen serials. Walker, who shared Everett’s love for the Eagle, first depicted Kremmen in a visual style whose realism was akin to that comic’s Dan Dare strip. The artist recollects that the final, cartoonish version came about because Kremmen needed to resemble the character depicted in the animated shorts, and Cosgrove Hall could not produce an animated version of Walker’s Eagle-inspired pencils in time for broadcast on the Kenny Everett Video Show (Walker).

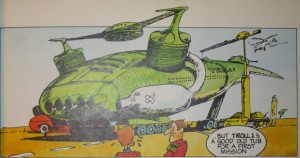

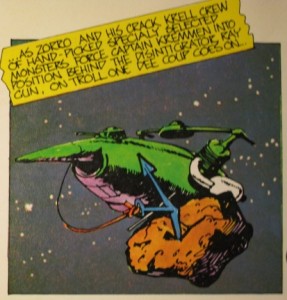

So, unlike Welch, the book’s artist did not emerge from the underground, but there are affinities between Walker’s art and the work of the comix creators. The design of the insect-like Troll 1 (see fig. 3 and 4), for instance, is visually distinctive, and its eschewal of aerodynamic slenderness reminds me of the spacecraft drawn by Vaughn Bodē, which also appeared unlikely candidates for defying gravity.

Fig. 3 and 4. Panels from Captain Kremmen and the Krells © 1977 Everex Marketing Company

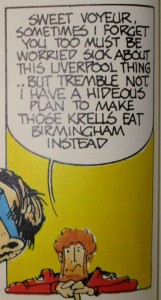

Walker’s attempt to visualise Everett’s fast-changing and unpredictable comic imagination led to the artist depicting a universe of ontological instability that chimed with the rejection of diegetic coherence that one observes in the comix. Walker inserted into the comic “Quick change surreal background objects. Objects that come and go for no reason but produce a strange tense world, which was supposed to run as a counterpoint to Everett’s own mad imagery.” (Walker) Other instances of formal experimentation include self-reflective devices, with Captain Kremmen offering asides to the reader, at one point resting his arms on the bottom of a panel and addressing us directly about the Krells’ plan to destroy Liverpool (see fig. 5). The underground hardly had a monopoly on characters rupturing the pretence of a self-enclosed fictional world, but comix creators did make use of this form of address.

Fig. 5. Panel from Captain Kremmen and the Krells © 1977 Everex Marketing Company

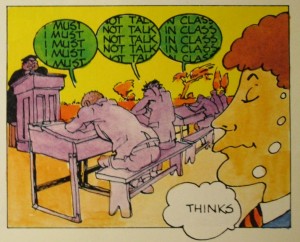

Walker’s attempt to capture the surrealism and formal play of Everett is evident early on in Captain Kremmen and the Krells, when Kremmen rips off the leg of a school bully, and the leg subsequently drips blood into the panel below. A teacher looks on through a window frame supported on a set of wooden legs, part of a strange, outdoor office set up in the middle of a field for no perceivable reason. Shortly after, in a panel that conveys the social enforcement of homogeneity of thinking, a row of schoolboys huddled over their desks think in unison “I MUST NOT TALK IN CLASS” (see fig. 6). This critique of conformity of consciousness accords with many underground comix texts from the 1960s and 1970s. From rock opera to psychological treatise many texts intended to reach countercultural audiences reflected this core position: the key institutions through which children in Western capitalist democracies are socialised are highly suspect because those institutions operate a system of reward and punishment that disciplines subjects into following lines of thought and behaviour that support the reproduction of an insidious socio-economic system and deter the possibility of alternative ways of living.

Fig. 6. Panel from Captain Kremmen and the Krells © 1977 Everex Marketing Company

There is one more way in which Captain Kremmen and the Krells evokes the underground comix, and that is the flaunting of offensive material, notably in terms of ethnic caricature. The book is riddled with stereotypes of German, Jewish, Scottish, Chinese and black characters. As with similar stereotypes used elsewhere in the underground (Robert Crumb’s depictions of African Americans being the most discussed), these images confront the reader with a mode of representation that exaggerates the physical attributes of (usually disempowered) ethnic groups in order to encode them with derogatory mental and moral characteristics. How we read the racial politics of such representations in the underground comix remains a subject of debate; commentators are undecided as to whether they are a progressive / satirical encounter with a repressed history of racism, or whether they constitute the casual recycling of unacceptable imagery.[iv] At this point I am reminded of the comment made by Everett’s biographers that the comedian never stopped to think about jokes such as “Let’s bomb Russia”; he was trying to make people laugh, without regard for the political meaning of those words, at that rally, at that particular point in history. Everett appears to have had little to do with Captain Kremmen and the Krells, but we could make the same point about the presence of offensive stereotypes in the book: getting a controversial laugh superseded reflection on what those stereotypes might mean and what their consequences might be.

Having the reached the subject of politics and provocative humour, we have returned to where we began. Artist Roger Wade Walker’s inventive reworking of storytelling conventions makes Captain Kremmen and the Krells a fascinating document in comics history. It was not Walker’s intention to mimic the underground but his innovations are akin to those found in the comix, and in the 1970s few British creators were experimenting in such a way in a long-length narrative.

May 2015

Endnotes

[i] The name of Captain Kremmen came from Superfun, a library of comedy “drop-ins” (very short audio recordings used on radio shows) produced by Mel Blanc, the voice actor, and his son Noel. The drop-ins from the Superfun library included mock adverts for products manufactured by the Kremmens company (Hogg and Sellers 230-33; Stafford and Stafford 154-55).

[ii] Everett made the two-minute episodes in his home studio, although exactly when he stopped doing so is unclear. When he left Capital in August 1980 he was no longer making episodes to air on his own show, although he appears to have continued recording episodes for the radio station (Hogg and Sellers 230-33; Stafford and Stafford 154-55).

[iii] It is difficult to work out who this joke is on: is this the grim humour of left-wing pessimism that recognises the UK’s political slide to the right, foreseeing a future in which draconian government makes it impossible for certain workers to go on strike? Or are we laughing at the Air Traffic Control Assistants for engaging in a futile industrial action, an atavistic political gesture whose backward nature is underlined by its impossibility in a technologically superior future? Or does neither apply?

[iv] Leonard Rifas wonders whether the stereotypical representations in the underground comix might raise awareness and “accomplish an anti-racist purpose” by helping “us better recognize this undercurrent in popular culture as a sickness” and leading one “to identify and reject such stereotypes.” In this way the stereotypical images in the comix may “cause less harm than more normal negative images, which make their insults beneath the level of conscious awareness.” William H. Foster, III’s survey of “The Image of Blacks (African Americans) In Underground Comix” sees the overwhelming use of these racist stereotypes as “satirical” (17) although novelist and scholar Charles Johnson criticises Crumb’s depictions of black people for not being “provocative in any positive way” (13).

Bibliography

Campbell, Colin. “Biytoo Books.” The Comics Journal 37 (Dec. 1977): 50-51. Alexander Street Press Underground and Independent Comics. Web. 30 Sept. 2014.

Foster, William H., III. “The Image of Blacks (African Americans) In Underground Comix: New Liberal Agenda or Same Racist Stereotypes?” Looking for a Face Like Mine: The History of African Americans in Comics. Waterbury, CT: Fine Tooth Press, 2005. 12-17. Print.

Hogg, James, and Robert Sellers. Hello, Darlings! The Authorized Biography of Kenny Everett. London: Bantam, 2013. Print.

Johnson, Charles. Foreword. Black Images in the Comics: A Visual History. By Frederik Strömberg. Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2003. 6-19. Print.

Rifas, Leonard. “Racial Imagery, Racism, Individualism, and Underground Comix.” ImageTexT: Interdisciplinary Comics Studies 1.1 (2004). Dept of English, University of Florida. Web. 29 Apr 2015.

Stafford, David, and Caroline Stafford. Cupid Stunts: The Life and Radio Times of Kenny Everett. London: Omnibus, 2013. Print.

Walker, Roger Wade. Email to the Author. 19 Nov. 2014.