CREATOR/S: Ian Miller

YEAR: 1978

PLACE: Brighton / Paris

PUBLISHER: Dragon’s Dream

ORIGINAL PRICE: Not known

PRINT RUN: Not known

WHERE CAN I READ IT FOR MYSELF? Billy Ireland Cartoon Library, Ohio State University

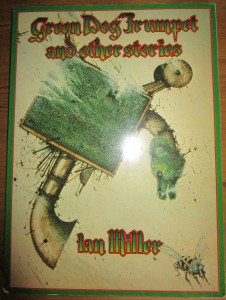

Figs. 1 and 2. Cover and spine of Green Dog Trumpet and other stories © 1978 Ian Miller

Ian Miller may need a little introduction but his art shouldn’t: anyone familiar with the Fighting Fantasy series, or the cover art for various SF / fantasy / horror books (including several Lovecraft volumes from the 1970s, see here), or the graphic novels The City (written by James Herbert) or The Luck in the Head (written by M. John Harrison) will have seen his work. Green Dog Trumpet and other stories (1978) appears fairly early in Miller’s career and represents an intriguing permutation of the trade paperback collection of short comics. It is also doing things with panels and layout I haven’t seen before; not in this way, at least.

The biography at the start of the book tells us that Miller was born in London on 11 November 1946 and that he studied at Northwich College and later at St. Martin’s College of Art in London. His website also states that he studied there, thus he joins several British comics creators who came through St. Martin’s (see Sabin for an account of some of the others). Miller was plugged into the fashionable transatlantic currents of 1970s fantasy illustration and animation; he designed backgrounds for Wizards (1977), the feature film directed by Ralph Bakshi (Bakshi also directed 1972’s Fritz the Cat). Green Dog Trumpet and other stories was published by Dragon’s Dream, the publishing imprint run by Roger Dean (responsible for some cracking Yes album covers). Dragon’s Dream also published two books of comics by French creator Phillipe Druillet, Lone Sloane / Delirius (probably released March 1978) and Yragael / Urm (I’ve yet to establish the year of publication to my satisfaction) (see fig. 3). Dragon’s Dream’s books include collections of commercial fantasy art linked by a single artist, or themed around specific collectives of artists (such as The Studio).

Fig. 3. Covers of Lone Sloane / Delirius and Yragael / Urm. Lone Sloane © 1972 Philippe Druillet/Dargaud Editeur, Delirius © 1973 Philippe Druillet/Dargaud Editeur, Yragael © 1974 Philippe Druillet/Dargaud Editeur, Urm © 1975 Philippe Druillet/Dargaud Editeur,

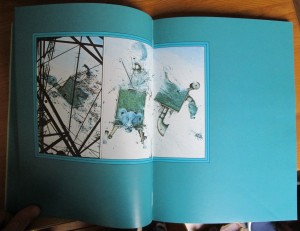

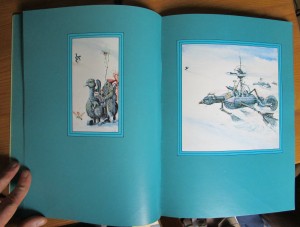

The wordless comics of Green Dog, loaded with spectacle and incredibly detailed art, fits into Dragon’s Dream’s other publications. There are five stories (see fig. 4), the longest of which, “The Triwag Chronicles,” is 23 pages long (including title page). These are enigmatic stories, fusing SF, fantastical and post-apocalyptic visual tropes (retrofitted technology, monumental apparatuses, fortified settlements and aerial battles); there is a discernible temporal progression with each panel transition, although the causality behind the actions of agents (‘why did they do that?’) is essentially unexplained.

Fig. 4. Page [7] of Green Dog Trumpet and other stories © 1978 Ian Miller

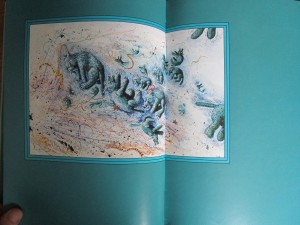

The edifices, war machines and mobile contraptions in the book do not seem to have been assembled to follow the laws of physics, rather they operate in a surreal tradition of infernal imagery: think Hieronymus Bosch and Max Ernst. The book’s biography outlines Miller’s background in “art history” and his identification “with the whole North European Expressionist tradition; from Brueghel to James Ensor, from Grünewald to George Grosz.” The artist Miller admires most is Albrecht Dürer. The word repeated several times in the epitexts in Green Dog is “Gothic,” and Miller’s style is certainly highly adorned, made up of medieval bawdiness and gargoylesque figures.

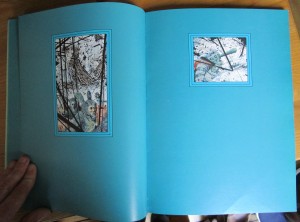

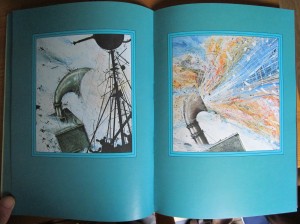

Figs. 5-7. Pages [24-29] of Green Dog Trumpet and other stories © 1978 Ian Miller

As well as his grounding in the worlds of fine art and art history Miller was the subject of exhibitions in 1973 and 1974 (both in London: the Greenwich Theatre Gallery and the Jordan Gallery). This is a key context for understanding Green Dog: surely the exhibitionist sensibility of the book – mimicking the experience of perusing an art gallery – is intentional. Miller has structured his panels as if one is walking past a long sequence of differently sized paintings (see the sequence of pages in fig. 5-7). In the title story, for instance, frames do not fill out the whole space of every page. One or two panels are positioned on each page and each panel has a double border, reproducing the effect of a painting framed and with an inlay. The composition of the images reflects this choice of staging since the panels show tableau akin to portraiture or landscapes, one after the other (there is one panel transition that could be described as a shift from one moment to another immediately after, namely, when the green dog trumpet emits a blizzard of canines; see fig. 8-9). Another two stories follow this vein, whereas “The Pequod Saga” and “The Triwag Chronicles” have multiple panels inside each inlay and ‘frame.’

Fig. 8-9. Page [30-33] of Green Dog Trumpet and other stories © 1978 Ian Miller

For each story all the space on the pages is filled out with a single, uniform colour depending on the story. The colours on each page are shown next to the relevant story on the Contents page (fig. 4). This reminds me of the colour-coding used for the floor plans that guide visitors around museums, not least art museums (e.g. Boston’s MFA and New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art). But why do this with a book of five separate comics where each one starts with a title page?

Bear with my suppositions for a while: let’s say that the title pages for each chapter anticipate that some readers will go through the book from start to finish, turning each page in sequence. The colour-coded pages, on the other hand, are aimed at a different kind of reader, one who plunges into the book at random. This reader has glanced at the Contents page and is glad of the orientation provided by the colour key. For such a reader, the book offers five sets of images to be surveyed: one might enter these sets at different points, admiring the images on display before departing to find another point of re-entry. You can make your way to the end of each story, one after the other and all the way through, or sample as much (or as little) of each section as you want.

Of course a reader of any comic can skip ahead, circle back or read the same page over and over. Green Dog seems to go further, expecting that some spectators will see the chapters, not as integral narratives, but as images available for contemplation. The aesthetic I am delineating here constructs the book as an art museum and each story as a separate wing (after all, a ‘story’ can be a narrative or a floor in a building). Green Dog came from a decade when the book of comics for adult readers was not as common as it is now: why not look to the institutions of the art world to provide a meaningful framework to gather short comics together? Further inquiry into the doubleness of Green Dog – its bookishness, its museum-ness – would be fascinating.

All of this makes the book sound very po-faced and sober but the last story is punchy, energetic, bawdy, brightly coloured and playful. You can get an idea of its contents from the title. What’s it called? “Trolley Dog Shag.”

August 2015

Bibliography

Sabin, Roger. “Some ‘Contemptible’ British Students.” The Education of a Comics Artist: Visual Narrative in Cartoons, Graphic Novels, and Beyond. Ed. Michael Dooley and Steven Heller. New York: Allworth Press, 2005. 214-20. Print.

Slattery, James. “Biography.” Green Dog Trumpet and Other Stories. Brighton/Paris: Dragon’s Dream, 1978. 10-11. Print.