CREATOR/S: Script by Roy Thomas, Art by John Buscema and the Tribe, adapted from the story by Robert E. Howard

YEAR: 1975

PLACE: New York

PUBLISHER: Marvel Comics Group

ORIGINAL PRICE: $1

PRINT RUN: Not known

WHERE CAN I READ IT FOR MYSELF? Michigan State University

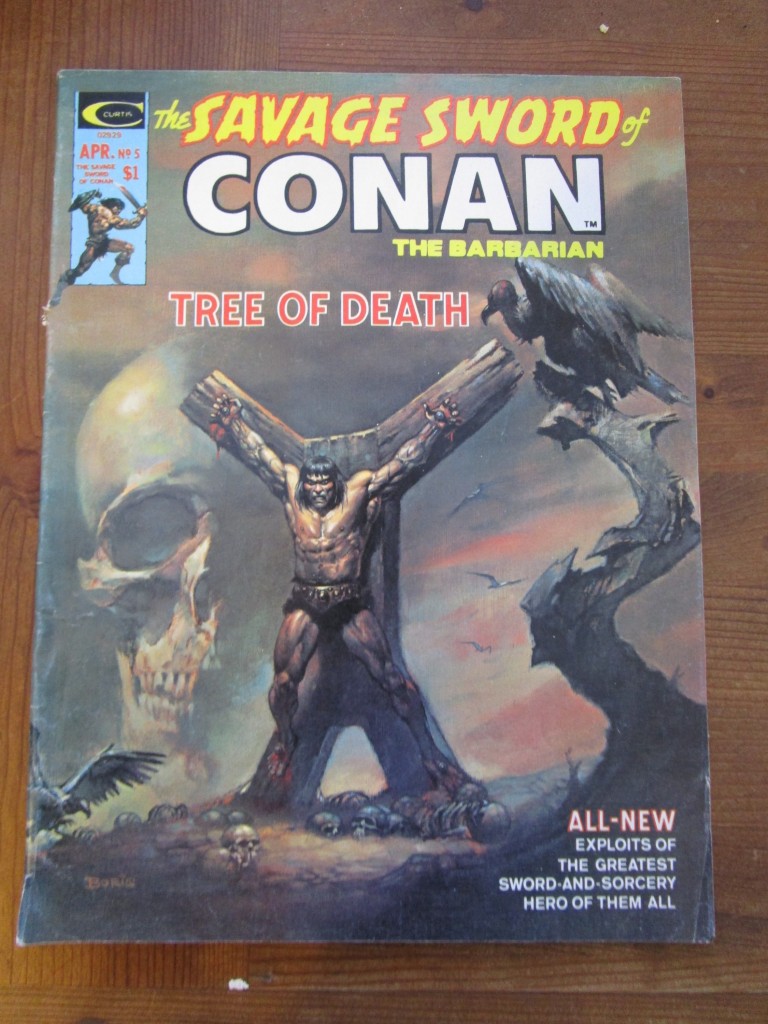

Figs. 1 and 2. Cover and spine of Savage Sword of Conan #5 © 1975 Marvel Comics Group

The fifth issue of Marvel’s Savage Sword of Conan, cover-dated April 1975, featured the “longest, mightiest Conan epic yet” (3), the 55-page story “A Witch Shall Be Born.” The length of the story permitted division into chapters, the breaks between which provided opportune sections for the placement of advertisements, somewhat reminiscent of Bart Beaty’s suggestion that Archie Comics “conceptualized its advertising material as akin to ads on the television and radio” (115).

“A Witch Shall Be Born” was not only notable for its length. The original Robert E. Howard story it was adapted from contained, according to the “Swords and Scrolls” letters page, “the single most famous episode in all of Conaniana: the barbarian’s crucifixion” (80). This is the central motif of the narrative, and given its iconic richness, it is appropriate that Boris Vallejo’s painting of this scene provides the cover to this issue (see fig. 1).

“A Witch Shall Be Born” was not marketed as a novel, but perhaps the comic writer Steve Gerber read it as such. In an interview with Gary Groth in August 1978, Gerber reflected on whether the world of comics could produce work “on the same level as a novel”:

the term ‘novel’ is rather all-encompassing. Robert E. Howard wrote novels. Unquestionably, to me, what Roy Thomas, John Buscema and Barry Smith have done with Conan is so far superior to the stuff that Howard turned out… so I suppose a certain kind of novel very definitely can be done in comics (37).

The Conan stories were frequently woven into debates in the long 1970s about the viability of graphic novels. Some fans loudly believed that Marvel’s careful exploitation of this literary property would usher in the long-length, book-published narratives the comics world had been anticipating. Some, it had to be said, scoffed at the idea that Marvel’s Conan tales would one day be stacked against the classic novels of American literature. Nonetheless, the commercial and critical success of the early Marvel adaptations by Roy Thomas and Barry Windsor Smith catalysed a cycle of sword-and-sorcery fantasy comics. Even The Comics Journal in April 1980 had praise for their collaboration, Kim Thompson writing that Thomas and Smith (as well as other creators) had set “particularly high standards” for the medium (7). The Comics Journal, it may be remembered, luxuriated in these “high standards” that the editors demanded, blazoning across the cover of the October 1980 issue the promise of “Yet Another Elitist Interview” within.

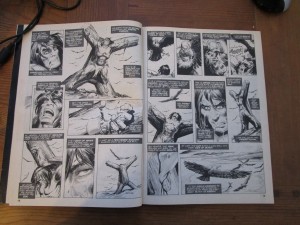

As with Marvel’s other black-and-white magazines, The Savage Sword of Conan was not sanctioned by the Comics Code Authority and was aimed at a slightly older readership. In terms of taking advantage of going without Code approval this was primarily manifested in scenes of implied sexual assault and more visceral violence (Conan up to his thighs in massacred enemies, severed hands etc.). Chapter three of the narrative, entitled “The Tree of Death,” is a wince-inducing episode that takes advantage of this license to show more bloody scenes than a newsstand comic book. This chapter narrates Conan’s crucifixion and eventual escape; it comes from Howard’s original material but there is something distinctively Marvel about it, evoking Stan Lee and Steve Ditko’s famous sequence from The Amazing Spider-Man 33 (Feb. 1966), when the web-slinging protagonist slowly and painfully lifts himself out from under heavy machinery. Conan’s release also comes slowly, an excruciating, drawn-out, dangerous disentanglement. By my count, Conan is left alone on the crucifix for 26 panels (see fig. 3), but once he is discovered it still takes 24 panels for the final nail to be removed.

Fig. 3. Pages 18-19 of Savage Sword of Conan #5 © 1975 Marvel Comics Group

On one level the crucifixion scene aligns Conan with the suffering Christ and is part of an overall tendency in “A Witch Shall Be Born” to re-use characters and iconography from the New Testament. The title refers to “Salome, the witch,” a manifestation of an eternal female character who recurs through history (and is always called Salome) to do evil work. Even when “a new world has risen on the ashes and dust– even then, there shall be Salomes to walk the earth — to trap men’s hearts with their sorcery— –to dance before kings— –and to see the heads of the wise fall at their pleasure!” (8) The latter speech aligns this Salome with the daughter of Herodias in the Gospels, who danced in front of King Herod; Herod was so pleased with the performance he granted the girl one wish, and she asked for the head of John the Baptist (Mark 6.21-29; Matt. 14.3-12). By the twentieth century the daughter of Herodias was commonly known as ‘Salome.’

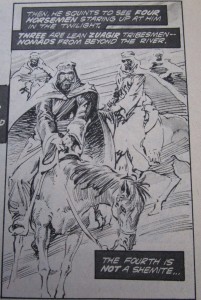

However, there is another Salome in the gospels, a disciple who witnesses Christ’s crucifixion (Mark 15.40). Where does she fit into this allusion? Furthermore, another Biblical reference, the bandits whom Conan sees as “four horsemen staring up at him in the twilight” (21), seems to work ironically, in that this equestrian quartet brings not the apocalypse but Conan’s salvation (see fig. 4). A reversal like this makes me think very carefully about Conan being bound to the cross. Perhaps it is wrong to see in this character’s crucifixion an allusion to Christ? At the very least, it seems worthwhile to burrow a little deeper in the image’s complex relation to that tradition.

Fig. 4. Page 21 of Savage Sword of Conan #5 © 1975 Marvel Comics Group

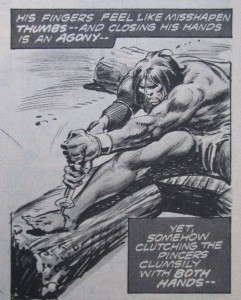

To begin with, the cross to which Conan is affixed is not shaped like the central motif of Christianity. This wooden structure looks more like an X, which gives Conan the appearance of being about to drop on his prey. Conan looks as menacing as ever on his crucifix; he has the aspect, not of humility, but of a tense energy wound tight and ready to spring. In fact, when a vulture flies in to peck out Conan’s eyes, the barbarian draws his head back in order to lunge forward when the bird is close. He catches it by surprise and breaks its neck with his bite. When the bandits release his hands, Conan finishes the job, pulling out the nails in his feet by himself (see fig. 5). Not even crucifixion can steal his strength away altogether.

Fig. 5. Page 23 of Savage Sword of Conan #5 © 1975 Marvel Comics Group

As the cover and the title of the chapter suggests, this is a “tree of death,” which seems an odd thing to say. The depiction of the crucifix makes it look bolted together from discrete parts and not carved out of a tree. There are trees of death in some religious traditions, so I wouldn’t rule that out as a reference point, but what if the tree of death doesn’t refer to the cross but the character? When the bandits consider how they will free the barbarian, they are concerned that in felling the wood they will kill the man in the fall. In order not to sustain injuries, when they chop through the base of the cross Conan makes “his whole body into a solid knot” and “holds his head rigid against the wood.” (22; see fig. 6) He avoids whiplash by making himself flush with the timber, and by tensing his body into a “solid knot” Conan turns himself into a rigid lump of tied of rope – or indeed, a piece of tough wood.

Fig. 6. Pages 22 of Savage Sword of Conan #5 © 1975 Marvel Comics Group

The crucifixion of Conan in the comic affirms his power and not his vulnerability. He does not suffer for our sins; suffering confirms that he is the man of wood, a living entity but a hardened one, able to remove the nails from his feet as if he were pulling them from a chunk of lumber. As thirsty as he is, he continues to go without water and rides ten miles in the desert. On the last page of the story, Conan has nailed Constantius to a cross, and rides off to leave him to die. It is a reversal of the earlier scene and indicates that the barbarian, the tree of death himself, has bested another enemy.

I’ve been re-reading the Roland Barthes of Mythologies (1957) recently, which may account for the speculative reading of signs in this post. Barthes might well have asked ‘what kind of ideological work is this image doing?’ The vultures and the skulls on the cover could have functioned as memento mori at an earlier point in the history of art, but here they are emptied out of their power, because we are in no doubt that Conan will survive this ordeal. This image does not valorize suffering or find sources of redemption, in this life or the next: it hymns the male figure as somehow unkillable, as a timber-hard figure resistant to the ordeals of thirst, hunger, heat, predation, exposure. The 1970s was the decade when environmentalism became the coherent, visible and militant movement it had never been before, when ecological concerns like overpopulation and over-foresting were the source of best-selling books and blockbuster films. In 1970 the Environmental Protection Agency was created in the USA and at the decade’s end President Carter called for a limit on American consumption in his “Crisis of Confidence” speech. The crucifixion of Conan can be read as a retort back to environmental anxieties, figuring the male human warrior as too powerful to be destroyed by anything as pathetic as being nailed to a wooden structure in a barren, hostile environment. When man (that seems the appropriate word here) takes on nature’s raw, unreflective hardness, the regenerative ability of vegetation and its pulsing urge to push out of the soil, then man can usurp nature’s power and triumph over it. Conan has managed this: even when nailed to a cross he is capable of posing a threat to nature, warning it away, and eventually (symbolically) unbinding himself.

Before I go, let me show you figure 7:

Fig. 7. Page 10 of Savage Sword of Conan #5 © 1975 Marvel Comics Group

I would say that the Anglophone eye (sorry, awkward, but you know what I mean) wouldn’t automatically go top left panel, right-hand panel, bottom left panel, but top left, bottom left, right. So the placement of the speech balloons is key if the panels are to be read in order, and how adeptly they’ve been placed to this end. Taramis’s jagged speech balloon takes us out of the first panel in this sequence and into the right-hand one, and placing Constantius’s face adjacent to Taramis’s balloon ensures that the reader is likely to contemplate his visage and words next. Well-crafted stuff indeed.

September 2015

Bibliography

Barthes, Roland. Mythologies. 1957. Trans. Annette Lavers. London: Vintage, 1993. Print.

Beaty, Bart. Twelve-Cent Archie. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 2015. Print.

Gerber, Steve. Interview by Gary Groth. The Comics Journal 41 (Aug. 1978): 28-44. Alexander Street Press Underground and Independent Comics. Web. 2 Oct. 2014.

Thompson, Kim. “Another Relentlessly Elitist Editorial.” The Comics Journal 55 (Apr. 1980): 6-7. Alexander Street Press Underground and Independent Comics. Web. 4 Dec. 2014.