CREATOR/S: Various (see below); edited by Pat Woolley

YEAR: 1977

PLACE: Sydney

PUBLISHER: Wild & Woolley

ORIGINAL PRICE: Not known

PRINT RUN: Not known

WHERE CAN I READ IT FOR MYSELF? The British Library, The National Art Library (V&A), the National Library of Australia

* The comics discussed below contain racially offensive language *

Fig. 1. Cover of Wild & Woolley Comix Book © TBC. Source: amazon.com

I have almost no information on this book and I won’t pretend that it’s a comics narrative aspiring to be a novel. It is little known (although it is mentioned in this interesting essay by Kevin Patrick) so readers will, I hope, be happy to hear a bit more about it. The bare facts: it’s called The Wild & Woolley Comix Book: Australian Underground Comix (1977), it’s black and white, and it reprints 109 pages of Australian underground comix originally published between 1964 and 1976. It was edited by Pat Woolley, reported to own one of the biggest comics collections in Australia in the Sydney Morning Herald. The creators in it are:

Ian McCausland

Neil McLean

Martin Sharp

Phil Pinder

Laurel Olszewski & Piotr Olszekski

Gerald Carr

Ernie Althoff & Peter Andrew

Peter Lillie

Peter Dickie

David Pride & Jack Rozycki

Carol Porter

Jon Puckridge

Bon Daly

Greg and Grae

Dave Bromley

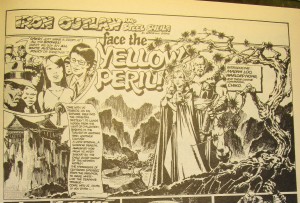

I’ll focus on the comix by Greg and Grae, which play heavily on the collection’s national context. These comix, featuring the characters Iron Outlaw and Steel Sheila, were originally published in the left-leaning independent newspaper Sunday Review. The first issue of Sunday Review came out on 11 October 1970 and it eventually merged with The Nation newspaper in 1972 to become the Nation Review (Carter 370 n.24). Unlike most of the other comix in Wild & Woolley Comix Book the adventures of Iron Outlaw and Steel Sheila form a brief (7 pages) but continuous narrative, the first page naming the story “Iron Outlaw and Steel Sheila Face the Yellow Peril!” [105] When the Sunday Review was launched it joined a cohort of other Australian newspapers that were celebrating “a new cosmopolitanism,” turning away from narrow definitions of Australian culture as white and British (Carter 370). “Iron Outlaw and Steel Sheila Face the Yellow Peril!” parodies the ‘Yellow Peril’ anxieties of late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century pulp fiction, which posed Asian hordes as threatening to swamp the bastions of white Euro-American civilization (see fig. 2). This danger was figured in individual villains like Dr Fu Manchu or (in thinly veiled form) Flash Gordon’s nemesis, the alien emperor Ming the Merciless. In Jack London’s short story “The Unparalleled Invasion” (written in 1907) the entire Chinese population represents a threat to the world and is represented as an insatiable, ever-expanding mass. The Yellow Peril was a menacing presence in fiction, film, comic strips and radio shows, often in the form of serial narratives. This rhythm of delivery is mimicked in Greg and Grae’s comic, apparently printed one page an issue: the first page ends “Tune in again, next week!” [105]

Fig. 2. Page [105] of Wild & Woolley Comix Book © 1970 Greg and Grae

It is easy to list the racist stereotypes in “Iron Outlaw and Steel Sheila Face the Yellow Peril!” Madame Loo heralds the arrival of Warlord Nong with “Gleetings Nong” and their homeland is an “eternal” “Oriental mystery,” a place “hidden from the light of civilization, basking in the twilight of another time: another culture.” [105] Cruel, dictatorial and hyper-sexualized, the Edward Said of Orientalism (1978) would recognise many of the themes on display in the depiction of the Asian characters. The story reaches a paroxysm of dehumanization when Loo and Nong prostrate themselves in front of a giant, amphibious Chairman Mao.

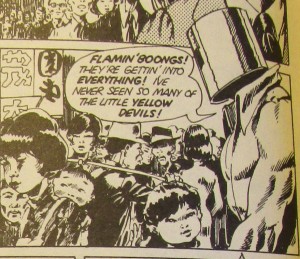

Loo’s plan to take over Australia and turn it into “Australoo” [105] is redolent of Yellow Peril anxiety about an inexorable invasion, potentially one from agents already inside white Western nations. Her forces have “infiltrated” Australia and “war shall begin from within!” From restaurants to factories and cinemas, Chinese immigration to Australia is shown to be nothing less than a conspiracy to wipe out the “poor, stupid round-eyes” [106] i.e. white Australians.

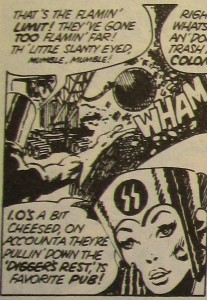

Fig. 3 and fig. 4. Page [106] of Wild & Woolley Comix Book © 1970 Greg and Grae

The heroes Iron Outlaw and Steel Sheila are avatars of an ethnically white Australia who resent the presence of Asian Australians (see fig. 2, fig. 3 and fig. 4) and their names hark back to white Anglo-Celtic settlement. The Iron Outlaw evokes folk hero Ned Kelly and Steel Sheila is named for the Australian slang term for a woman, one that probably derives from “the large number of Irish migrants to Australia.” (“Meanings”) The language of Iron Outlaw and Steel Sheila is marked by phrases such as “That’s the flamin’ limit!” [106], “corker!” [107], “Geez, I feel crook!” [108] and “whingin’” [109], and when Iron Outlaw is drugged, kidnapped, tortured and brainwashed, he is brought back to his senses by the flames of a dragon. In other words, he returns to the side of good after he is “bar-b-qued!!!” [110] (see fig. 5). What could be more Aussie than that?

Fig. 5. Page [110] of Wild & Woolley Comix Book © 1970 Greg and Grae

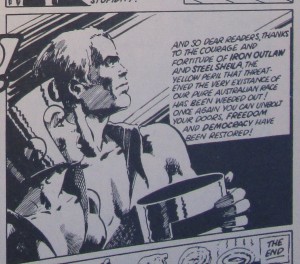

While the comic is open to the charge that in satirizing racist caricatures it nonetheless reproduces them, there can be no doubt Greg and Grae are attempting to put critical distance between their comic and the Yellow Peril tradition they are mocking. Through hyperbole and ridiculousness, the racist fears of the Yellow Peril genre are outlined and undermined. Readers are meant to laugh at the hysterical captioning of Madame Loo as “EVIL, EVIL, E-V-I-L!” [105] and at the idea of a secret undersea tunnel connecting Asia to Australia. At the end of the narrative Iron Outlaw and Steel Sheila get back to Canberra in time to warn the authorities: Madame Loo’s “mighty armada” is defeated at sea and the “fifth columnists [who] eagerly await” the arrival of the “invasion fleet” [110] are marched away. Madame Loo’s anguished cry of defeat refers to the Yellow Peril genre’s investment in white superiority and Oriental dissimulation. “Our fiendish Asian cunning and inscrutability were no match for British ignorance and stupidity!” [111] Loo’s conspiracy confirms that racist white Australians’ worst fears are correct: there is an elaborate conspiracy to transform the country’s racial order, and Asian immigrants and their children are working from within to erase white settler culture. But, also like many Yellow Peril texts, the plot assuages white supremacist fears by staging the downfall of Asian invasion. The idea that the genre flatters a precarious sense of white racial selfhood is underlined by a caption stating Madame Loo’s plot is “more than the Caucasian mind can comprehend” [105], which implies how Yellow Peril texts drew narrator and reader together as shared members of the “Caucasian” race, both horrified by Loo’s plans.

Fig. 6. Page [111] of Wild & Woolley Comix Book © 1970 Greg and Grae

Fig. 7. Nazi propaganda poster (c) 2011 United States Holocaust Memorial Museum

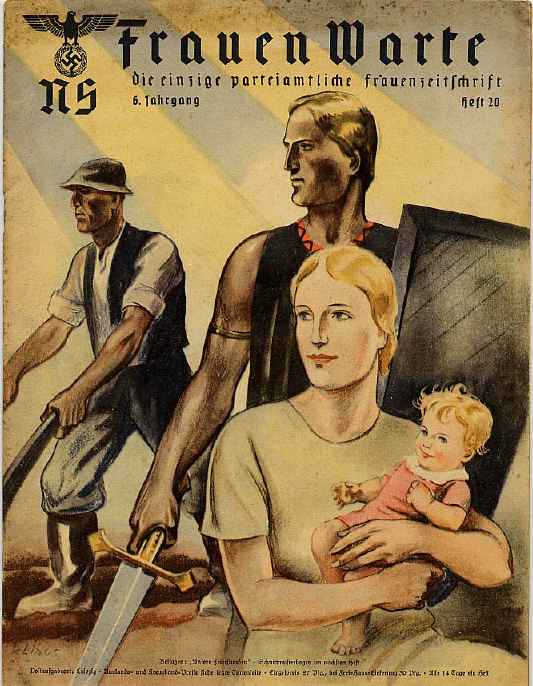

Fig. 8. Magazine cover with no copyright information provided. Source: http://alphahistory.com/nazigermany/women-in-nazi-germany/

“Iron Outlaw and Steel Sheila Face the Yellow Peril!” may be warning that the racist stereotypes and plots of Yellow Peril popular fictions inform white Australian anxiety about being swamped by non-white immigration. Greg and Grae stridently criticise anti-immigration sentiment by linking the protagonists’ racism to German Nazism. The initials on Steel Sheila’s helmet (see fig. 4) look like the insignia of the SS, and the penultimate panel of this story thanks the heroes for preserving “our pure Australian race.” Iron Outlaw and Steel Sheila stare out of the panel towards an unseen point in the distance (see fig. 6), adopting the stylized posture of Nazi propaganda, the heterosexual Aryan couple resolutely fixed on a better future off-frame (see fig. 7-8). As Greg and Grae indicate, those racial fantasies can go clothed in the language of “freedom and democracy” as well as fascism and totalitarianism.

December 2015

Bibliography

Carter, David. “Publishing, Patronage and Cultural Politics: Institutional Changes in the Field of Australian Literature from 1950.” The Cambridge History of Australian Literature. Ed. Peter Pierce. Melbourne: Cambridge UP, 2009. 360-90. Print.

“Meanings and Origins of Australian Words and Idioms.” Australian National Dictionary Centre. Canberra, The Australian National University. 31 Dec. 2015. Web. 30 Dec. 2015. *

* Pleasingly, due to the time difference between the UK and Australia, the date this page was last updated really is after the day I consulted it. My research travels forward in time now.