In this week of all weeks, it seems a good idea to post some thoughts on comics and the US Presidency, adapted from the talk I gave in November with Dr Sinéad Moynihan as part of the University of Exeter’s US Presidential Election lecture series. There isn’t anything to do with 1970s graphic novels though! Here we are:

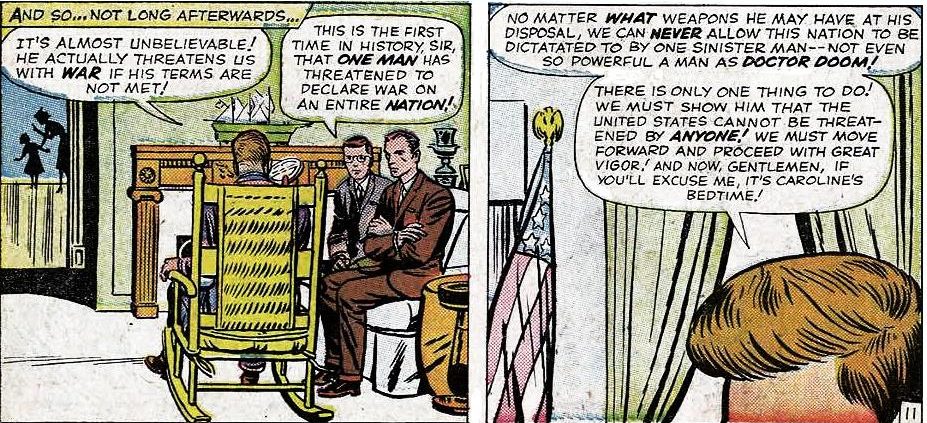

Presidents of the United States have been turning up in comics for decades. Sometimes they appear at the end of episodes in order to heap accolades on victorious heroes; on other occasions they add verisimilitude when supervillains threaten the world. Issue seventeen of The Fantastic Four from August 1963 shows a distinguished character in a rocking chair contemplating an ultimatum from the evil Doctor Doom, who has threatened that unless he is given a position in the President’s cabinet he will go to war against the United States (fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Stan Lee (writer), Jack Kirby (art), and Dick Ayers (inking), “Defeated by Doctor Doom!” Fantastic Four 17 (Aug. 1963): 11, rpt. in Marvel Masterworks: The Fantastic Four, vol. 2 (Tunbridge Wells: Panini, 2007), 187. © 1963 Marvel Characters, Inc.

President John F. Kennedy is not named in this interlude – we don’t even see his face – but the hairline and the reference to JFK’s daughter Caroline make it clear who we’re seeing. Responding to the demands made by Doctor Doom, writer Stan Lee gives this character dialogue that would not be out of place in some of President Kennedy’s most famous speeches. When the JFK character says “No matter what weapons he may have at his disposal, we can never allow this nation to be dictated to by one sinister man” there are echoes of the promise made in Kennedy’s inaugural address that “every nation” must know that America will “pay any price, bear any burden, meet any hardship […] in order to assure the survival and the success of liberty.”[i]

Perhaps more interesting than the times when American presidents appear in comics is when fictional characters make a bid for the US Presidency. Bill Griffith’s character Zippy the Pinhead first ‘stood’ as a candidate in 1980, when T-shirts promoting Zippy’s candidacy became must-have items amongst his supporters.[ii] But the most notable campaign organised for a comics character has to be when Pogo the Possum stood for President in 1952. That was the year Dwight D. Eisenhower was elected to the White House, and his supporters wore badges proclaiming ‘I Like Ike,’ which the Pogo campaign mimicked with the slogan ‘I Go Pogo.’ Even though the cartoon possum lost, his creator, cartoonist Walt Kelly, was undaunted and another ‘I Go Pogo’ campaign took place in 1956.

Walt Kelly had worked as an animator for Walt Disney on films such as Dumbo, Pinocchio, and Cinderella, but he left the Disney Studios in 1941 and used his drawing talents to create ‘funny animal comics.’ In the first issue of Animal Comics (December 1942) Kelly drew a comic about the inhabitants of Okefenokee Swamp, a bayou in the American South. Many of these characters were anthropomorphic animals such as Pogo the Possum, Albert the Alligator, Howland Owl, and a turtle called Churchy LaFemme. Kelly eventually moved from comic books to newspapers, taking up a job with The New York Star in 1948 that involved drawing political cartoons and producing a daily newspaper strip in which Kelly re-used his characters from Okefenokee. By the mid-1950s the Pogo strip was a huge success and editors across America bought the rights to reprint it in their newspapers.[iii] Pogo had over 50 million regular readers and Kelly was earning over $150,000 a year.[iv]

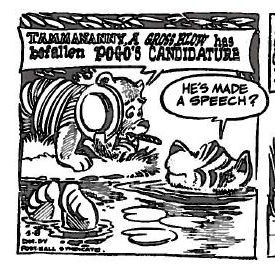

As Kerry D. Soper’s book We Go Pogo: Walt Kelly, Politics, and American Satire (2012) reminds us, Walt Kelly conceived of the ‘I Go Pogo’ election campaign as a neat way of raising the strip’s profile.[v] The campaign began in Pogo in February 1952 with the arrival of Tammananny the Tiger in the Okefenokee Swamp. This was an allusion to Tammany Hall, the political organisation based in New York associated with the symbol of the tiger. The Tammany Hall “machine” was synonymous with corruption, favouritism, and vote-rigging.[vi] When Tammananny cannot find a suitable candidate for the presidential race the animals of the swamp force Pogo to be the nominee against the honest possum’s wishes. To oversee his campaign a bear called P.T. Bridgeport enters the strip and becomes Pogo’s campaign director. As his name suggests, P.T. Bridgeport has more than a touch of P.T. Barnum about him. When P.T. Bridgeport speaks Kelly uses lettering in the style of a Big Top banner (see fig. 2) and the bear brings a touch of show business to the campaign trail.

Fig. 2. Walt Kelly, Pogo, 8 May 1952, rpt. in Pogo, vol. 2 (Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2012), 145. © 2012 Okefenokee Glee & Perloo Inc.

Between February and November 1952 the Pogo strip was filled with political satire about mechanical voters and back-room deals and throwing hats into the ring (literally). Kelly wove the election-year calendar into the strip’s daily episodes and the inhabitants of Okefenokee Swamp set off for Chicago during convention season (both the Republicans and Democrats held their conventions in Chicago in 1952).

While the ‘I Go Pogo’ campaign was taking place inside the newspaper strip, Kelly was touring the country, rousing support for his creation to be the next president. We Go Pogo describes these as a mixture of knowingly ridiculous stump speeches and serious lectures about art and politics; Kelly’s public appearances were usually held on university or college campuses.[vii] By the end of the 1952 campaign 150 colleges endorsed Pogo as their candidate. According to Soper the cartoonist took enormous care preparing for these public appearances. Kelly’s assistant studied college newspapers in advance of the visits and made a list of the issues that interested the students Kelly was going to address. Campus newspapers and student governments were sent packs of material to help promote Pogo’s bid for the presidency including mock news releases about the campaign’s progress. The cartoonist also drew one-off promotional illustrations specific to each college newspaper.[viii] A handful of journalists and student publications were acknowledged in the Pogo daily strip: the barge that the characters use to travel to Chicago changes name several times and in one strip it is called The Crimson and in another The Orange (which I presume are references to the Harvard Crimson and Syracuse’s The Daily Orange). Badges featuring the ‘I Go Pogo’ slogan were a central arm of the campaign and in 1952 Kelly received requests from 50,000 students for these promotional items. The badges were mentioned within the newspaper strip at every opportunity, and characters wearing them proudly showed their badges off; in one episode, Churchy finds a novel use for them, holding up his underwear.

Things got out of hand, however, when the ‘I Go Pogo’ campaign came to Harvard University on 15 May 1952 and clashes between Pogo supporters and the police left three officers injured and 28 students arrested. The New York Times reported:

Five thousand Harvard students rioted for four hours in Harvard Square tonight when a satirical political rally called to boom “Pogo-for-President” erupted into a bottle and beer can fight with club-swinging police. […] [This] latest outbreak of collegiate “spring-fever” rioting […] began with the arrival of Walt Kelly […] to speak at a mock convention.[ix]

According to Soper the cartoonist actually arrived after the battle and was appalled at the police’s brutality (he still gave his stump speech). Soper dials down the scale of the skirmish, putting the number of students gathered in Harvard Square at 1,600. He reads the riot as a flashpoint for pre-existing tension between local residents and students: police officers had apparently shouted “Getting arrested will teach you Harvard bastards a lesson!”[x]

Nonetheless Soper thinks there were wider political implications to the ‘I Go Pogo’ election phenomenon. He argues that one of the reasons college students claimed Pogo the Possum as their presidential nominee was because this was a socially tolerated way of openly expressing disaffection with the political system. Supporting the ‘I Go Pogo’ campaign was a safe way for students flirting with liberal politics to express their discontent with the status quo.[xi] Kelly, it is worth remembering, risked censure in the early 1950s by mocking the witch-hunts against communists; the cartoonist based the character Simple J. Malarkey on the prominent anti-communist politician Senator Joseph McCarthy. Like the Pogo strip itself, the students who flocked to rallies for a cartoon president were humorously mocking the way that politics was conducted in 1950s America, though this took place within well-defined, socially acceptable limits. At Harvard on 15 May 1952, though, the students’ challenge to authority got tangled up in local antagonisms and the ensuring violence was national news.

January 2017

Notes

[i] Qtd. in Hugh Brogan, The Penguin History of the USA, 2nd ed. (London: Penguin, 2001), 613-14.

[ii] “Newswatch,” The Comics Journal 56 (May 1980): 16.

[iii] Mark Evanier, “About Walt Kelly,” in Pogo by Walt Kelly, vol. 2 (Seattle: Fantagraphics, 2012), 335.

[iv] Kerry D. Soper, We Go Pogo: Walt Kelly, Politics, and American Satire (Jackson, MS: UP of Mississippi, 2012), 36.

[v] Soper, We Go Pogo, 200.

[vi] Brogan, The Penguin History of the USA, 399-400.

[vii] Soper, We Go Pogo, 117.

[viii] Soper, We Go Pogo, 34-36, 200.

[ix] “5,000 Riot at Harvard,” The New York Times 16 May 1952: 14; italics not in original.

[x] Soper, We Go Pogo, 3, 203-04.

[xi] Soper, We Go Pogo, 204-05.