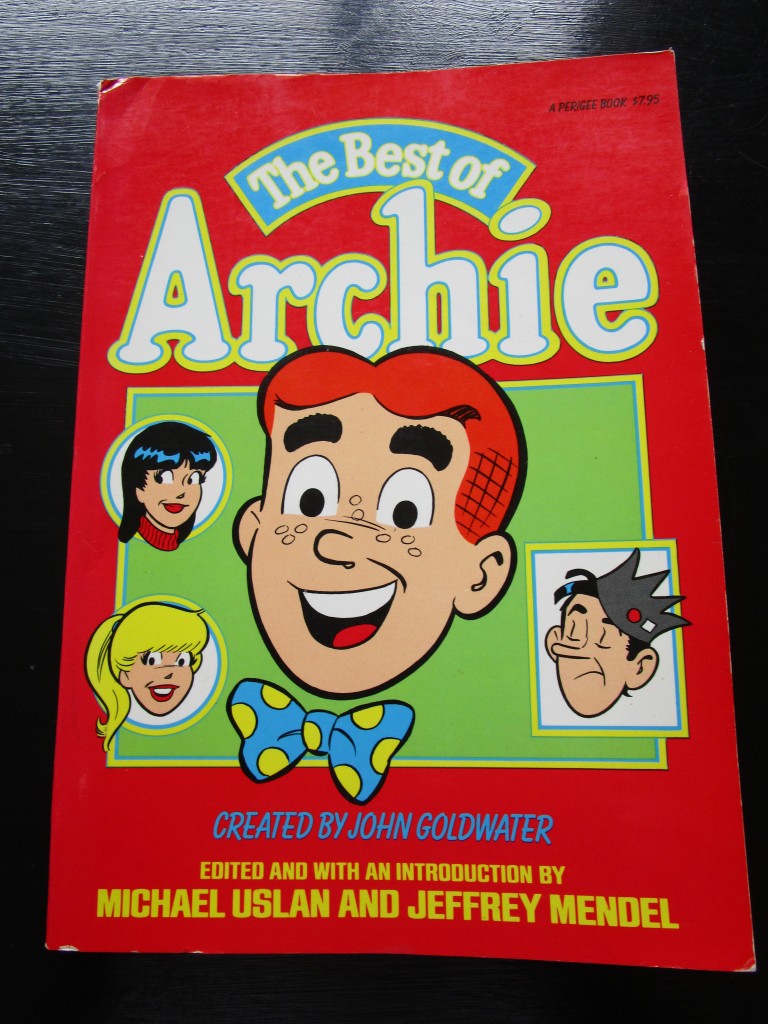

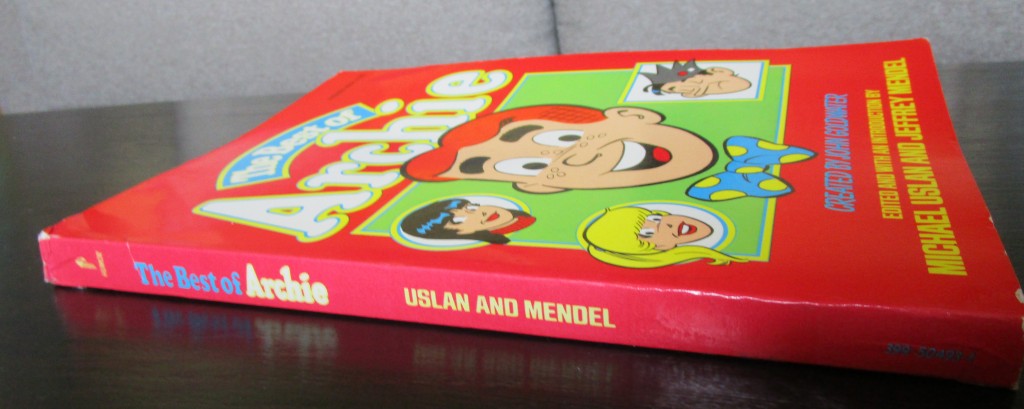

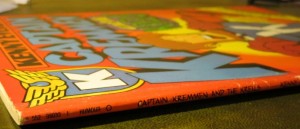

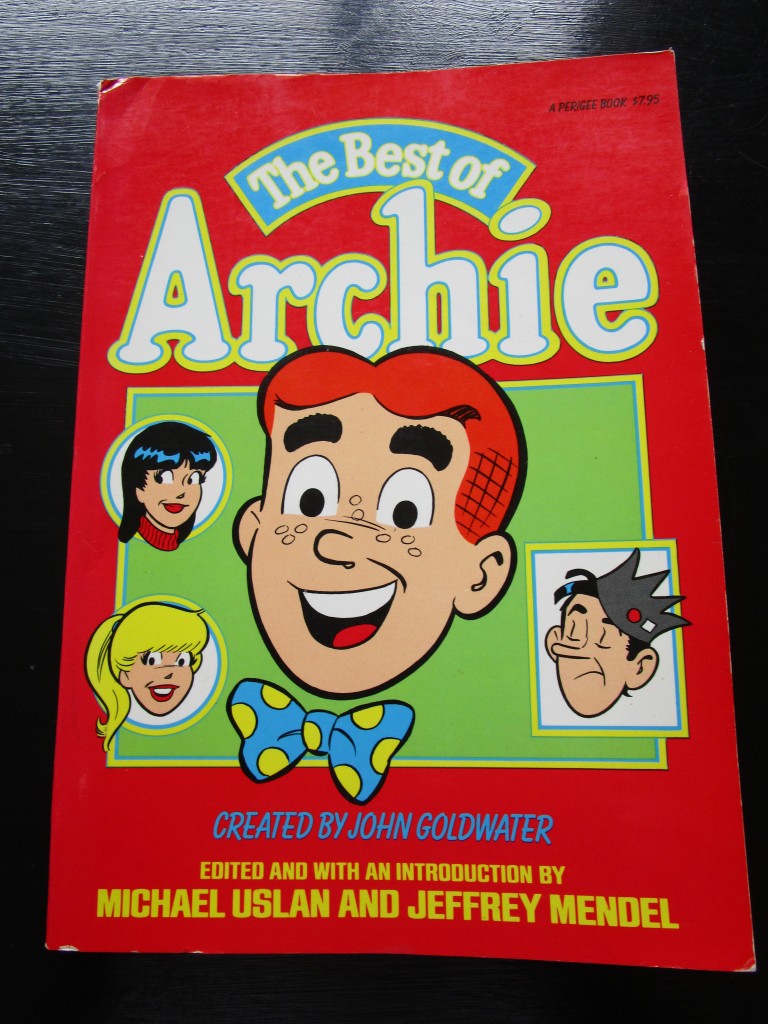

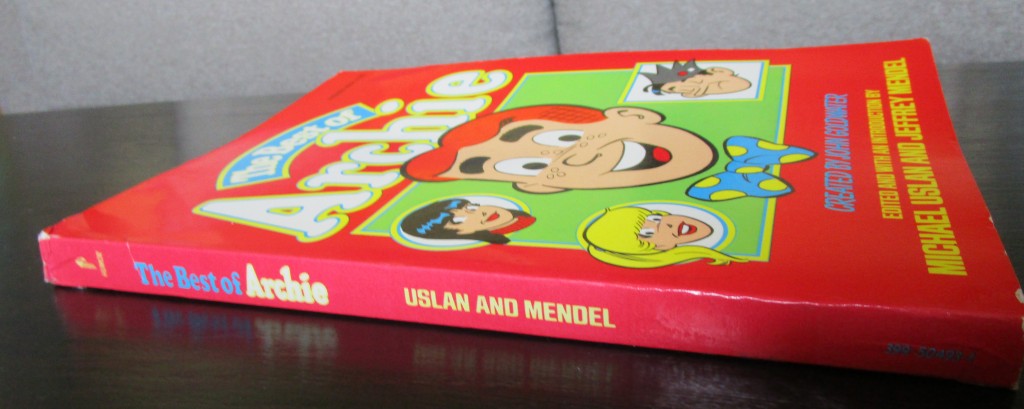

Figs. 1 and 2. Cover and spine of The Best of Archie © 1980 Archie Comics Publications, Inc.

2010s Nostalgia for 1970s Nostalgia for the 1950s

In 1970s America the 1950s were in vogue. This could be seen in the reruns on TV, the lyrics of Don McLean’s song “American Pie” (1971) and films such as American Graffiti (1973) (actually set in early 1960s). From the 1950s and earlier, the nostalgia movement plundered the twentieth century for styles that could be brought back and sold to consumers. Film and fashions alike reflected this obsession with the commodities that constituted America’s national past (Carroll 71, 297).

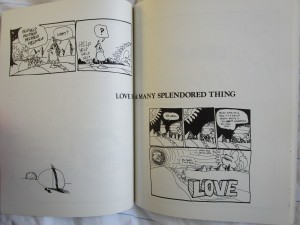

The teenage comic character Archie Andrews first appeared in 1941. His fictional world – Riverdale High School, Pop Tate’s Choklit Shoppe, the dating and the trips to the beach – is of a piece with that mid-twentieth-century culture the United States hankered for so powerfully in the 1970s. As the introduction to the 1980 book collection The Best of Archie puts it, “At first glance, it appears that the strip had remained virtually static since the early days. The same characters are at the same malt shop, in the same jalopy, on the same beach, and in the same school doing the same things they were doing during World War II.” (Uslan and Mendel 9-10)

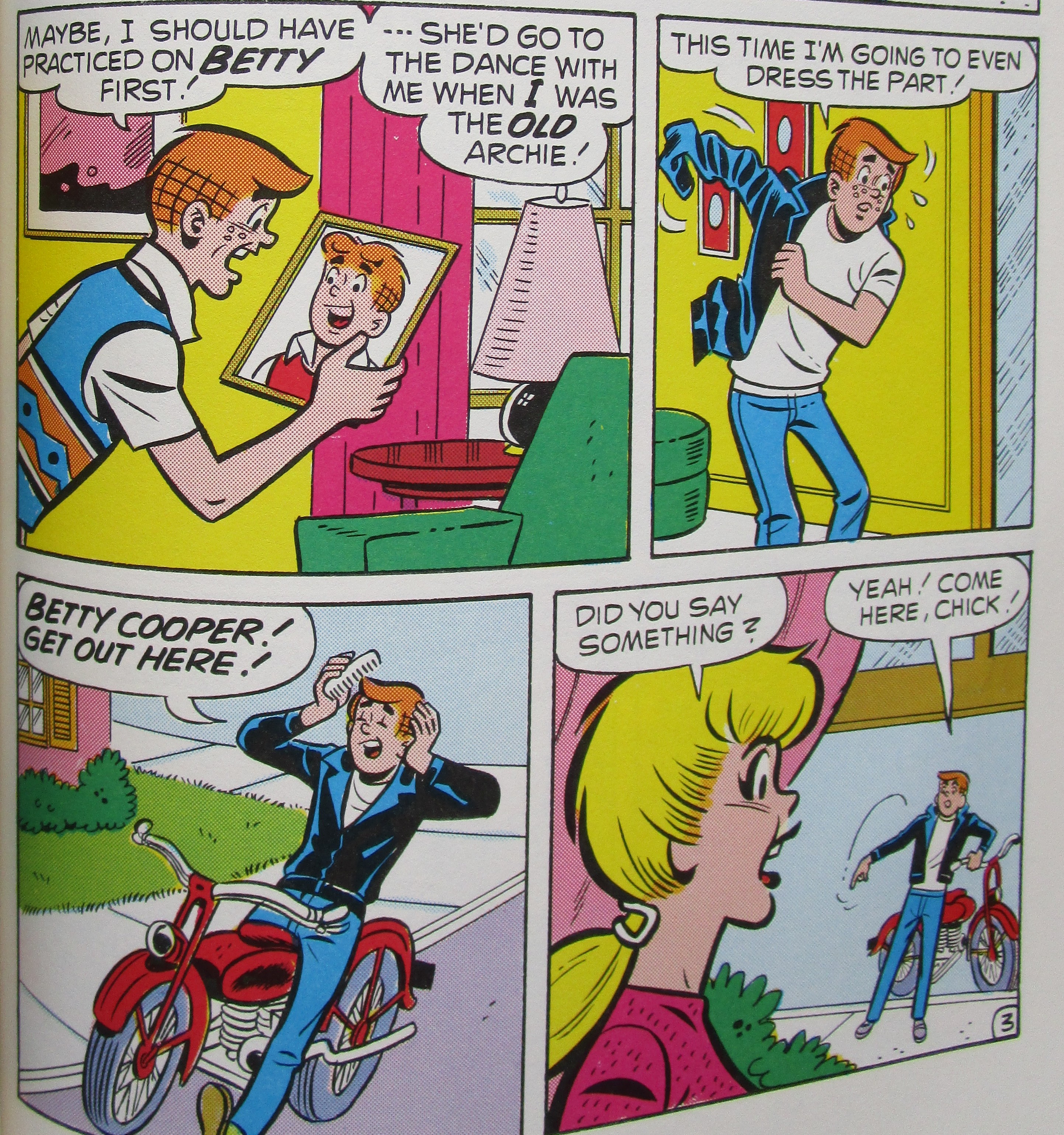

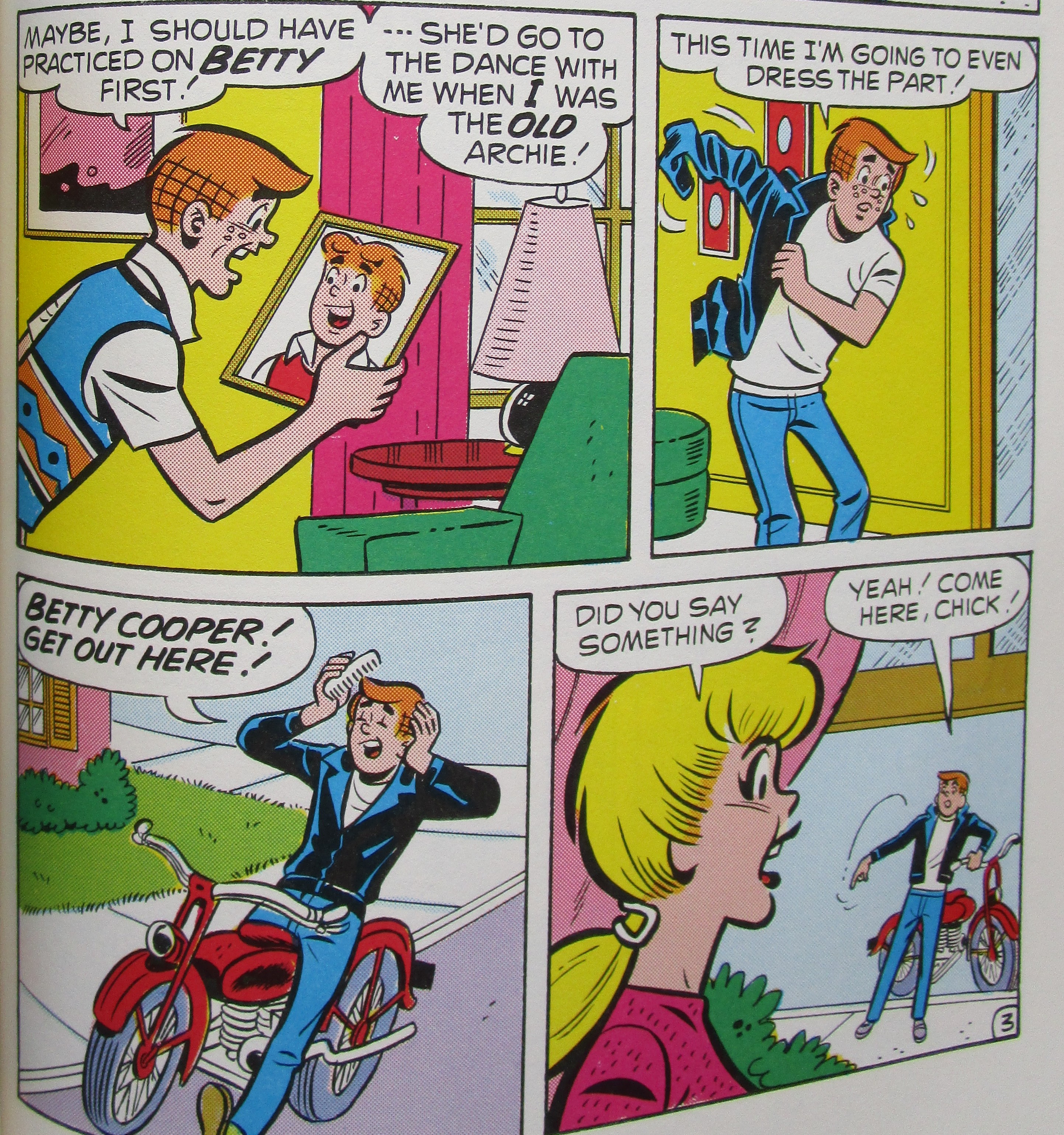

Fig. 3. Page 185 of The Best of Archie © 1980 Archie Comics Publications, Inc.

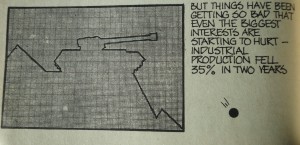

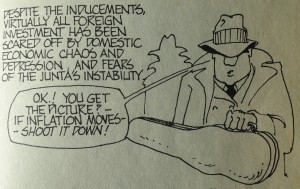

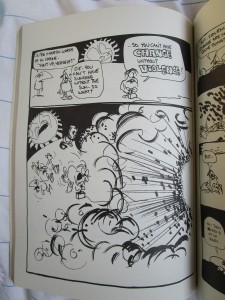

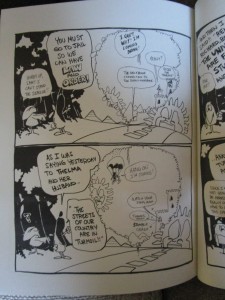

The early 1970s Archie story “A Fool for Cool,” reprinted in The Best of Archie, plays with 1950s nostalgia in what builds up into a feedback loop of allusion. The plot is simple: a television show, clearly a version of Happy Days,[1] has made a star of the character “Funzee” – a bequiffed, leather-jacket-wearing, motorbike-riding lothario. Archie is advised that if he wants “to get anywhere with girls” (183) he needs to adopt the ways of Funzee and just tell the girls in his life they’re going to the dance with him. So Archie has his hair cut like Fonzie, sorry, “Funzee,” and tries to be forceful with Veronica. She tells him to leave. Archie throws on Funzee’s white t-shirt and leather jacket and turns up outside Betty’s house to tell her she’s coming with him (fig. 3). Betty’s parents collapse with laughter; Betty refuses and suggests Archie has been watching too much TV. Later, the three teenagers sit in the Choklit Shoppe eating sundaes, and Veronica and Betty explain to Archie that “just because we dig a character on TV doesn’t mean we’d dig him in real life!” (186) It’s Archie and not Funzee they want – but when a friend rushes in to announce “the guy who plays Funzee on TV is making an in-person appearance at the supermarket” (187) Betty and Veronica knock their table over in their rush to see him. They run off, calling Funzee’s name, as Archie lies dazed on the floor covered in ice cream (fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Page 187 of The Best of Archie © 1980 Archie Comics Publications, Inc.

For much of this comic we might think it is a morality tale on the seductions of popular culture, a particularly self-reflexive reminder that the image-world of the 1950s found in 1970s mass media is a set of representations for which no actual referents exist. These can be enjoyed when they appear in their allotted exhibition space (“we dig a character on TV”) but we should be highly suspicious if they are taken to have some sort of weight in our lives. Given that the debut of Happy Days “coincided almost exactly with the collapse of Archie comics’ sales” (Beaty, Archie 6) we could read this critique as a defence reflex. Archie comics are protecting their territory from the new interloper.

But wait… is “A Fool for Cool” implying that readers should be just as suspicious about the Archie comics and the Riverdale they show us? One could read this as the comic interrogating itself, proposing that what is being depicted is not so much the 1950s themselves but the 1950s that America wished it had experienced between the 1940s and 1960s: peaceful, fun, affluent, full of adventure and with times of fruitful maturation ahead.

The joke, of course, is that Veronica and Betty may well care for Archie himself and not Funzee but as soon as the actor turns up in the vicinity they run off to see him. Perhaps this is part of the story’s critique: we knowingly indulge in the nostalgia boom, fully aware that the 1950s didn’t look like it does in Happy Days but wilfully suspending our disbelief. Veronica and Betty have mastered this process, and in some senses are the nostalgia boom’s ideal consumers, not Archie: because Archie believes that the 1950s lives he emulates can be inhabited and exert social leverage in the world, he can be snapped out of that belief too. The two women know that Funzee is not real and that his forceful attitude towards females is risible, but they crave the pleasure of seeing him in the flesh, a different type of investment in the aura of presence. And because it is seemingly more knowing, it is shaken less easily. If I was out to try my readers’ patience, I’d elaborate on this possibility: “A Fool for Cool” dramatizes a clash of consumption practices in the middle of the twentieth century. Archie is persuaded to become a modern consumer who invests in the characters of serial narratives and feels a personal stake in their existence (there’s something of Jared Gardner’s Projections here); Betty and Veronica are postmodernist consumers whose cynical distance in no way mitigates the impassioned pleasure they take from characters whose verisimilitude they deride.

The final image has Archie prone and confused (perhaps he’s been reading my blog) and Pop Tate looks on, silently laughing. The final twist in the tale? The Choklit Shoppe was, according to the introduction in The Best of Archie, “the soul and inspiration of ‘Arnold’s’ on the TV show ‘Happy Days’” (Uslan and Mendel 9) and Beaty thinks Arnold’s is “essentially” a direct copy of the Choklit Shoppe (Archie 184). I’m trying to work out who the joke is on: the character Archie, for sure. Also the Archie comics themselves, trumped by a televisual successor? Does Pop Tate’s final presence remind readers that the original is the best, the authentic, the one and only, or has his – and Archie’s – laughter been stolen away by the usurper Happy Days?

The Pureheart Returns

The Best of Archie, which reprints all of its comics in full colour, tries to capture the variety and major permutations of the Archie franchise. There are historical fantasies, gangster daydreams, SF adventures, stories where Dilton and Chuck are the protagonists, or Betty and Veronica, or Jughead, or Little Archie. It reprinted the origins of Pureheart the Powerful, Archie’s superhero alter ego, a story which originally appeared in Life with Archie #46 (Feb. 1966). In this story the red-headed teenager learns how to transform into a super-powered crime-fighter by calling upon “the power of the pure heart!” (71)

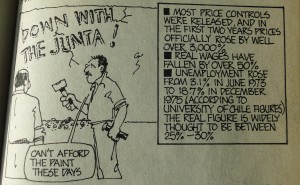

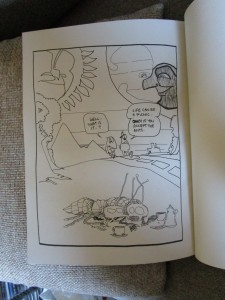

Fig. 5. Page 75 of The Best of Archie © 1980 Archie Comics Publications, Inc.

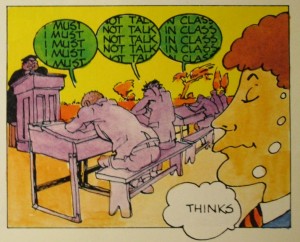

In a swipe against generic conventions, Archie’s suit inexplicably repairs itself between his stints as Pureheart. The suit repairing itself is not so unusual, but superheroes don’t usually draw attention to this illogical (but highly convenient) commonplace in the genre (fig. 5).

Why Buy Old Comic Books When You Can Buy Books of Old Comics

Jules Feiffer started it. When a newspaper cartoonist like Feiffer edits a lavish book of mid-twentieth-century superhero comics for the respected Dial Press, the hacks raise one eyebrow. When it includes an articulate introductory essay drawing on Feiffer’s experience as a pro, the hacks sit up. And when that book coincides with a hubbub of media attention about hip superheroes and comics on campus, further stoked by the popularity of the Adam West Batman TV series… no wonder Feiffer’s The Great Comic Book Heroes (1965) caught the imagination of comics fans in the mid-1960s.

It wasn’t until the next decade that comics companies and trade publishers really joined forces to reprint the comics of eras past. These book collections often had some stories from the 1970s but made a virtue of presenting the best of comic book history back to the late 1930s. The Best of Archie contains comics from the 1940s, 1950s, 1960s, 1970s and 1980s.

Where the books reprinting Marvel comics are concerned, check out Robert G. Weiner’s Marvel Graphic Novels and Related Publications: An Annotated Guide to Comics, Prose Novels, Children’s Books, Articles, Criticism and Reference Works, 1965-2008 (2008). I won’t list every title in Weiner’s bibliography, but the Marvel reprint activity includes:

- The Marvel Collector’s Album series that Lancet Books brought out (1966-67).

- The so-called “Origins books” published under Simon and Schuster’s young adult imprint Fireside Books (1974-79).

- The Pocket Paperbacks series that began in 1977 and ran into the 1980s.

- Grosset & Dunlap’s Ace Tempo paperbacks, which often reprinted fairly recent comics series (e.g. Battlestar Galactica, Conan the Barbarian) linked to properties popularised by other media. These seem to start in 1978.

I don’t know that anyone has compiled a similar bibliography for DC’s books, but where the 1970s is concerned it would need to include:

- Three book collections of DC comics printed by Fireside Books: America at War: The Best of DC War Comics (1979), Heart Throbs: The Best of DC Romance Comics (1979), and Mysteries in Space: The Best of DC Science-Fiction Comics (1980).

- Grosset & Dunlap’s Ace Tempo paperbacks of DC superheroes. I have five: Superman, The World’s Finest, The Justice League of America, Wonder Woman, Superboy and the Legion of Superheroes (all published 1977-78).

- Secret Origins of the DC Super Heroes (1976), published by Harmony (a division of Crown Books).

- From 1972, the Paperback Library’s two-volume Green Lantern starring Green Arrow.

- Also from 1972 a book of Wonder Woman comics published by Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Two substantial (380+ pages) collections by Bonanza Books from 1971: Superman: From the 30’s to the 70’s and Batman: From the 30’s to the 70’s (rogue apostrophes in the original titles).

The hardback collection of Wonder Woman comics published by Holt, Rinehart & Winston was a collaboration between Holt and Ms. Magazine. Gloria Steinem wrote the introduction and the prefaces to many sections, explaining Wonder Woman as a feminist icon. Sacks suggests there was a corporate, as well as ideological, synergy between America’s most prominent feminist magazine and the DC superhero. Ms. began in July 1972 and was bankrolled and published by DC’s corporate owner (85).

It was not only big trade publishers repackaging stories from old comic books. Robert K. Wiener’s Archival Press brought out three books at the end of the 1970s: Miss Fury (1979) by Tarpe Mills, in which crime-fighter Miss Black Fury defends the US from a spy ring, the SF adventures of Spacehawk (1978) by Basil Wolverton, and the horror / SF short stories that Berni Wrightson wrote and drew between 1968 and 1971 collected in Back for More (1978).

Remember this is hardly a conclusive summary, and I’m not even talking about the reprint collections of newspaper strips.

Archie-cana

The 1970s book collections enabled later generations to familiarise themselves with the history of the medium. This preservation of texts was justified on the grounds that here is a window onto the nation’s cultural soul, a common enough defence for the study of American comics (Beaty, Art 29). Carmine Infantino’s short introduction to Secret Origins of the DC Super Heroes asserted that America’s superhero comics were an unappreciated vernacular form, akin to woven blankets or blown glass: “The craftsmen who created the stories in this volume were worried about feeding those voracious presses, not about how posterity might judge their work.” And as “with jazz and American films, the Europeans – particularly the French – recognized cultural value in what most natives dismissed as so much fish-wrapping, the comics. They […] have given a cachet of respectability to a vital part of our folk art” (11). Let others decide the cultural worth of the comics in the stale air of posterity: the craftsmen that hewed these texts were too busy rolling their sleeves up and earning an honest living to do so themselves. In Infantino’s telling the early comics creators were grappling with the locomotive energy of a bustling cultural industry and maintaining the vivacity of America’s popular culture. Infantino’s choice of words implies these comics deserve reprinting because they provide an “insight into national character” (Beaty, Art 29), in this case American dynamism and graft.

The related rationale is that these comics are primary sources for historical study. Michael Uslan’s edited collection America at War included “some of the ads that appeared with the war stories. […] They’re there just to remind you of what some folks were trying to sell you back then.” (4) This volume also included a “DC War Comics Bibliography” (243-45) and an “Index to DC’s 1950s Frontier War Comics” (247) so eager researchers can track down the entire DC war comic output at marts, conventions and comic shops.

Both impulses are apparent in The Best of Archie. As the introduction explains, the cast of characters reproduced in the collection have become “part of Americana.” Archie himself has taken “his place in American folklore” and his “roots are all-American” (Uslan and Mendel 7-13). The two-page “The Archie Archives,” a brief listing of the runs of comics featuring Archie, is provided to assist readers who want to track down the entire history of the character. And it is clear that the selection of comics has been made with an eye on the Archie comics as a barometer of changing American values, from transient fads (CB radios and video tapes) to more profound social issues and morals (communes, racial prejudice and the women’s movement). In fact these comics seem very carefully chosen to express, in the words of Archie co-publisher John Goldwater, how the Archie comics “have to be relevant to the year in which we’re publishing or we’ll start losing our readership” (qtd. in Uslan and Mendel 10). “Don’t Quote Me” (1980), a story in which Mr. Weatherbee gets “hooked on the preaching of […] a phoney prophet who preaches simple living from the back seat of a limousine” (152-54), seems to have been included to prove that the comics are hip to the self-awareness movement (which was really a 1970s phenomenon, but you get the idea).

The Pureheart Triumphant

The Best of Archie was edited by Michael Uslan and Jeffrey Mendel. In the 1970s Uslan wrote some Batman stories for DC and by the time The Best of Archie was published he co-owned the movie rights to the character of Batman. Uslan would go on to be an executive producer on all the Batman films from Batman (1989) onwards.

Archie for Sale

The Best of Archie was sold for $7.95 (in paperback) and $14.95 (in hardback). These prices were consistent with other reprint books: the Marvel Fireside Books, which had the same page dimensions and were also in colour, ranged from $3.95-$7.95 (paperback) and $10.95-$14.95 (hardback) (these prices are taken from the Pacific Comics Catalogue for Aug.-Oct. 1980). In January 1977 Clay Geerdes reported that the Secret Origins of the Super DC Heroes paperback was retailing for $6.95. The Wonder Woman hardcover retailed at $12.95.

This Blogpost Is Just a Cheap Rip-Off of Bart Beaty’s Twelve-Cent Archie, Isn’t It?

Imitation is the sincerest form of parody. No, wait, parody is the lowest form of wit; irony is the second cousin of flattery. Or, as Mr. Weatherbee puts it, “Time is the salad dressing of life.” (151)

July 2015

Endnotes

[1] Do I have to explain what Happy Days was? Yeesh. OK, it was a nostalgic early 1970s sitcom set in the 1950s and revolving around the lives of a group of teenagers. The milieu bears some similarity to the world of Riverdale, and red-headed star of the show Ron Howard, who played the character Richie Cunningham, bore some resemblance to Archie Andrews. I mean, ‘Richie’ is virtually ‘Archie’…

Bibliography

Beaty, Bart. Comics Versus Art. Toronto: U of Toronto P, 2012. Print.

—. Twelve-Cent Archie. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 2015. Print.

Carroll, Peter N. It Seemed Like Nothing Happened: America in the 1970s. New Brunswick; Rutgers UP, 1990. Print.

Gardner, Jared. Projections: Comics and the History of Twenty-First-Century Storytelling. Stanford: Stanford UP, 2012. Print.

Geerdes, Clay. Comix World 64 (15 Jan. 1977). Print.

Infantino, Carmine. Introduction. Secret Origins of the DC Super Heroes. Ed. Dennis [sic] O’Neil. New York: Harmony, 1976. 11. Print.

O’Neil, Dennis, ed. Secret Origins of the DC Super Heroes. New York: Harmony, 1976. Print.

Pacific Comics Catalogue #12 (Aug.-Oct. 1980). Bound within The Comics Journal 59 (Oct. 1980). Alexander Street Press Underground and Independent Comics. Web. 18 Dec. 2014.

Sacks, Jason. American Comic Book Chronicles: The 1970s, 1970-1979. Raleigh, NC: TwoMorrows, 2014. Print.

Uslan, Michael, ed. America at War: The Best of DC War Comics. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1979. Print.

Uslan, Michael, and Jeffrey Mendel, eds. The Best of Archie. New York: Perigee, 1980.7-13. Print.

Weiner, Robert G. Marvel Graphic Novels and Related Publications: An Annotated Guide to Comics, Prose Novels, Children’s Books, Articles, Criticism and Reference Works, 1965-2008. Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2008. Print.