Our next Screen Talks will be on Monday 4th November at Exeter Picturehouse. Dr Sam North (Senior Lecturer in Creative Writing, Dept of English) at the University of Exeter) will introduce Plein Soleil (Rene Clement, 1960), the renowned French adaptation of Patricia Highsmith’s novel The Talented Mr Ripley (1955).

Join the event on Facebook and find out more here.

Booking Information: Book online, call the Box Office 0871 902 5730 or buy tickets on the door (half price for students on Mondays).

Dr Sam North has written a guest blog-post for us on the film and questions of adaptation:

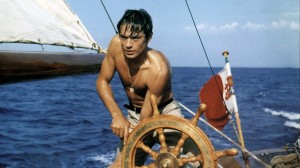

From the outset Plein Soleil is impressive for its vigour and energy, and its sexuality: the truly amazing handsomeness of Alain Delon, playing Tom Ripley, is immediately given a sinister slant just as pointed as his cheekbones when he finds the girl’s earring in his hand. We learn of Tom’s mission to bring home the wayward, rich Philip Greenleaf to the bosom of his family; and what interests me, from a technical point of view, is the entrenched, permanent engagement of dramatic irony which secures and deepens our involvement in the story from the moment that Tom Ripley sticks the knife into Philip Greenleaf.

It’s a stylish film: from the title sequence we are plunged into a fast, optimistic world, although not an innocent one; and the speed with which lengths of celluloid can be cut together and made to work for a seasoned cinema-going audience is part of its charm. Its deftness, its light touch – the feeling that one needs to run with this film to keep up – has the charm of Jean-Luc Godard’s A Bout de Souffle, which kicked off the French New Wave and went on to influence a diverse range of directors from QuentinTarantino to Wes Anderson.

My own experience in the world of adaptation – I sold novels to the film industry in the UK and in America for a number of years – has given me an understanding of what a film needs to find in a novel. Sometimes it is only an idea, or a character, and at other times, as is the case with this film, it is a fully-fledged dramatic structure – but it is always like feeding time at the zoo: a film is merciless in its chewing up of a book to get out of the text what the film’s creators believe will make the film successful, and that can be a painful and (if a book falls into the wrong hands) clumsy process. As a writer I have adapted The Wind In The Willows for the iPad (www.bibliodome.com) and it was an intensely rewarding piece of work; it felt like it was a sort of ‘loving’ of the text, taking a step beyond reading it, and I am proud of the result. The medium into which one is adapting determines many of the creative decisions, but, as is so often the case with writing fiction and poetry, it is the restriction itself that produces the invention.

Come along and enjoy Plein Soleil. It is enough merely to gaze at a youthful Alain Delon.

Sam writes novels and screenplays, and lectures in Creative Writing at the University of Exeter. Read more about Sam’s work here.