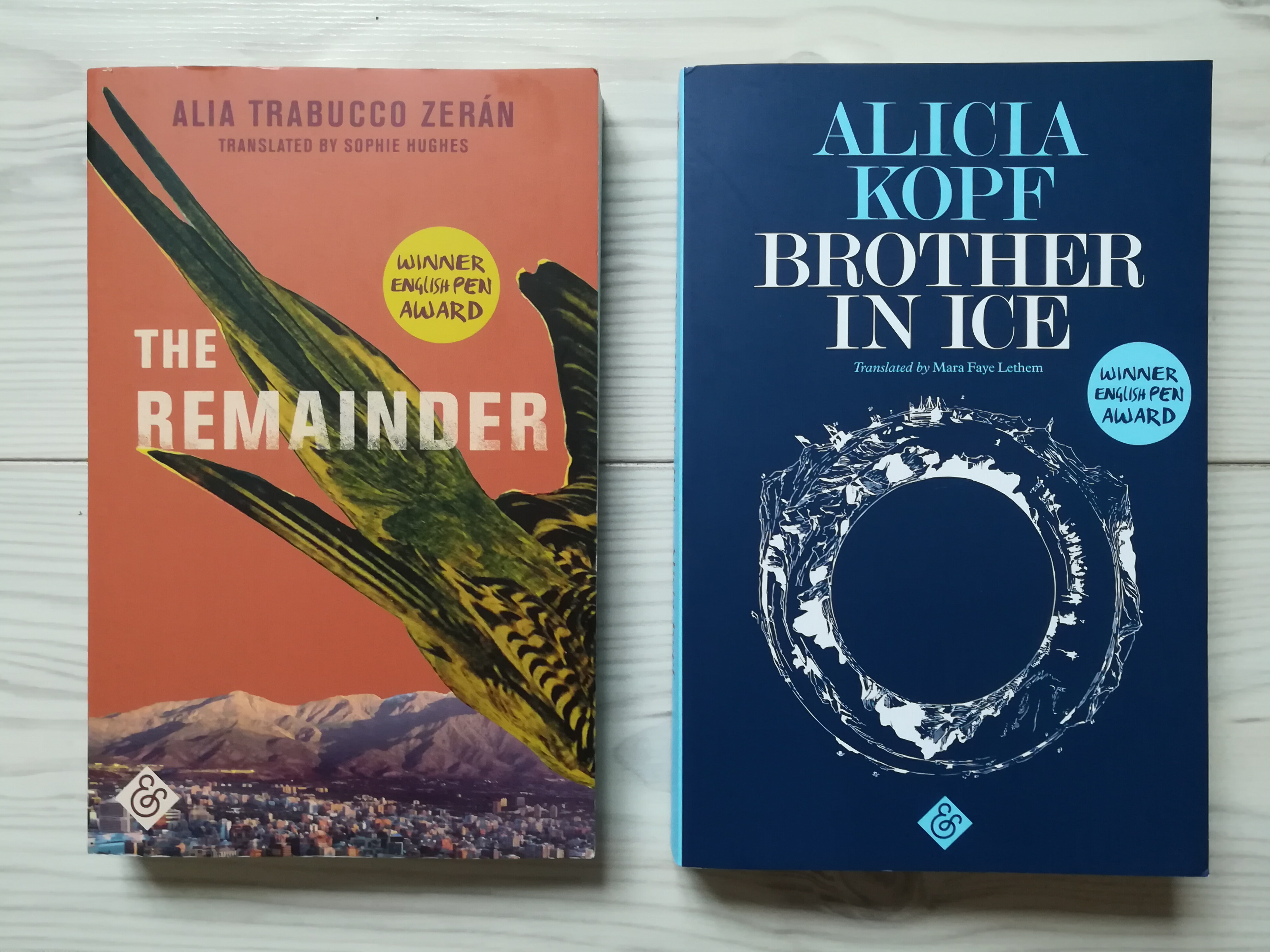

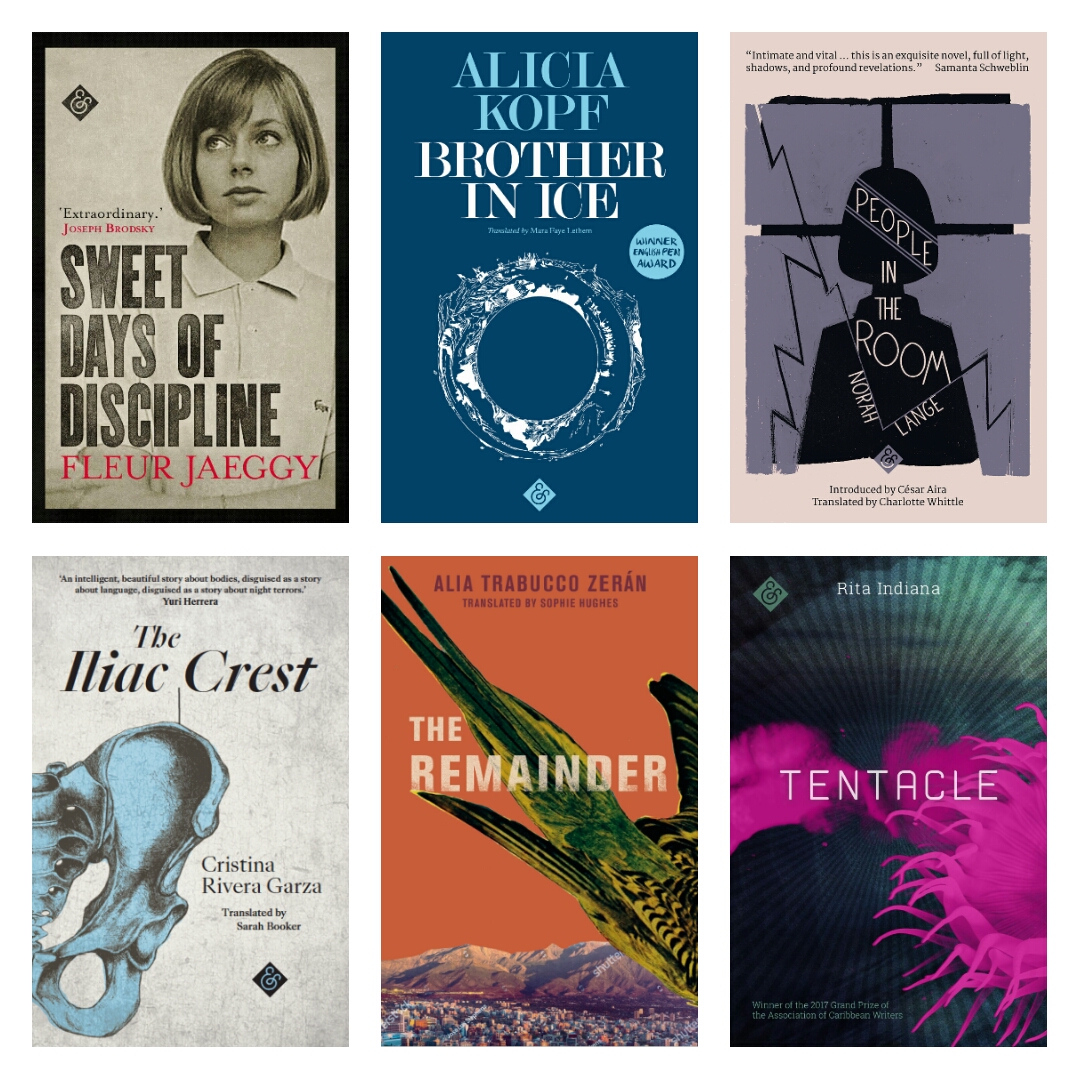

Earlier this year I had the pleasure of talking to Nicky Smalley, publicist at And Other Stories, about their commitment to the Year of Publishing Women. As many of you will know, in 2015 Kamila Shamsie issued what she termed a “provocation”, a challenge to publishers, to mark the centenary of women’s suffrage in the UK by making 2018 a Year of Publishing Women. And Other Stories was the only press to take up the challenge, and they have published a fantastic selection of women’s writing this year – in English and in translation. While all of them are excellent, I can’t pass up the opportunity to give a special recommendation for two debut novels: Alia Trabucco Zerán’s The Remainder, a literary road trip well worth taking in a sublime translation from Chilean Spanish by Sophie Hughes, and Brother in Ice, a beautiful, experimental novel by the immoderately talented Alicia Kopf, translated from the Catalan by Mara Faye Lethem.

It’s widely acknowledged that independent publishing is a brave business, built on passion and commitment, and Nicky shared some fascinating insights into And Other Stories’ decision-making process for the Year of Publishing Women. Firstly, I asked Nicky what And Other Stories hoped to achieve when they made the decision to take part in the Year of Publishing Women, and she set out two very clear objectives:

“One was just to be part of a conversation and to move the conversation on, and to create, and show people that you can do this, it’s not that hard. You can make decisions about what you publish in order to effect change that you feel or be part of the change that you want to see. And it needn’t be a massive inconvenience and it’s not about disadvantaging your male authors, they’re still going to get published. Another reason for it was that we publish so much translation, and we are aware of the fact that women are massively under-represented in terms of what gets translated, and even though we have very small lists, because we publish so much translation we are able to make a difference.”

While some publishers responded to Shamsie’s provocation by saying that they had their schedules set, or that they didn’t want to disadvantage their male authors, And Other Stories rearranged their schedules with minimal disruption, putting male-authored texts back for 2019. This meant that they had to look harder to find books to fill their schedule for 2018, and Nicky cites this as one of the greatest things to come out of the Year of Publishing Women for them – discovering writers that they otherwise might not have come across. And this itself fed their second objective: being part of a change that they wanted to see.

“Men are favoured, considered more serious, considered to write better literature and so on, and so they’re the ones that get the awards, they’re the ones that get the coverage in the news that bring them to the attention of foreign publishers who might want to publish them.”

So you might think that And Other Stories was already a female-centric press, and indeed Nicky describes the team as “determinedly feminist”, but she notes that they were quite shocked when they looked at their own lists and saw that the majority of what they had published was by men. As a company, they have always challenged the mainstream and tried to be representative of diversity in society, but even so they found that the back catalogue – especially in terms of translations – was predominantly male. So I asked Nicky why this might be, and she had some thought-provoking reflections in response:

“There were a lot of different factors that have led to that, not least of which is that most of what’s submitted to us is books by men. We’ve monitored some statistics, because we have an open submissions policy, and even though we were having this year of publishing women, we still found that most of the submissions we got from men and from women were books by male writers. And we went out specifically to all the agents we know and said that we were only going to be publishing women, so agents were already submitting more women than was the general case for open submissions. But still it was interesting to us that even though we’d expressly said that we were doing this, we were still getting these submissions from male writers. The other reason why we’ve published so much writing by men in the past is because most of what gets translated has already had a level of success in its original language, and often, in a lot of cultures, more attention is given to male writers. Men are favoured, considered more serious, considered to write better literature and so on, and so they’re the ones that get the awards, they’re the ones that get the coverage in the news that bring them to the attention of foreign publishers who might want to publish them.”

Confirmation of this bias within the global publishing industry is sobering, and highlights how important it is to do something about this in the UK. Though And Other Stories cannot change this single-handedly, it’s certain that their being part of this conversation made others take it more seriously. Even if large publishers or other large independent publishers didn’t take up the Year of Publishing Women, other things have happened that may well have been a result of And Other Stories doing so. As Nicky puts it, “unless someone had come out and said ‘yes, we’re going to do this’, other people would have allowed it to slide away. So it feels good to have done it.”

The impact of the Year of Publishing Women

Despite negative article titles at the start of the year, such as “2018 won’t be the ‘year of publishing women’ after all” and “What became of 2018 as the year of publishing women?”, a high-profile backlash on diversity from Lionel Shriver, and a general reluctance within the industry to make significant changes (evidenced by the low take-up of Shamsie’s “provocation”), there has still been some progress. It may be too early to know what the legacy of the Year of Publishing Women will be going forwards, but Nicky made some interesting reflections about potential effects that I’m going to expand on here:

Firstly, and in response to my musing above about the importance of English-language gatekeepers actively promoting change, one key change is the message being sent to literary agents: if more women writers are sought, then this might have a knock-on effect on the gender hierarchy in the publishing industry in their own countries. As Nicky explained, “Publishing is a market, and literature generally is subject to some market forces, even if not always in the same way as some other more commodified things, but if this conversation is happening in the UK, and if we’re saying that we want to see more books by women, then that potentially has an impact on the possibilities for women writers in other countries as well.”

Secondly, in terms of what gets submitted to prizes such as the Man Booker International Prize, And Other Stories usually submit around 8 books. Ths year, all of their submissions will be women writers, and that makes a significant change to the statistics. We all know the difference that the exposure of a Man Booker win can make: look at Han Kang and Deborah Smith, or Olga Tokarczuk and Jennifer Croft, for example. But the shortlisting and longlisting can make a difference too: La Nación recently published an article on Argentine literature in the UK, making reference to MBI longlisted authors Samanta Schweblin and Ariana Harwicz, and the exposure these two authors gained – along with the others on the lists – is considerably greater because of the prestige attached to the prize.

So this brings me to wonder: how do we measure success? By literary prizes, by sales figures? At the time I spoke to Nicky, it was too soon to tell whether sales were up or down for 2018, though it seemed fairly consistent with the same period the previous year. But one wonderful outcome is, quite simply, the books that And Other Stories have identified and published. They have expanded the scope of their list, and published things that they may not have come across otherwise, all while maintaining their own ethos and commitment to diversity in the publishing industry. I mentioned in an earlier post that small changes can make a big difference, and it seems to me that this small publishing house is making an enormous difference to the literary scene. One of Nicky’s comments that has really stayed with me epitomises the importance of openness, at a time when the UK is perceived to be closing itself off:

“The more you show willingness to find these things, the more they emerge. And also readers, who want to read these books, suddenly become aware that they’re there. I’m sure there are lots of readers who’ve always known it’s there, but the gatekeepers, the publishing industry, haven’t let the voices through, so the readers haven’t been able to encounter them. They shouldn’t have to search that hard. It should be there, they should be able to find it, and it’s about being part of helping that, increasing the availability of great literature, that also represents a wide range of experiences.”

On this last point, Nicky did tell me how they struggled to find books that were representative of a diverse range of society, and so there is clearly still work to be done towards true equality and diversity in publishing. But none of it can happen without a starting point, and And Other Stories have certainly given us that: in the long-term, they will continue to work with some of the writers they’ve published this year, which shows that the Year of Publishing Women hasn’t been a passing phenomenon, but one that is set to keep influencing the literary translation market in the UK over time. Not to mention the political stand they have taken: And Other Stories depends on subscriptions because of their publishing model, and this means that all subscribers this year have received exclusively books written by women. And Other Stories have made headlines in literary magazines and mainstream press, and anyone reading those cannot fail to receive the message they are sending out: Bring us your women writers. There is no compromise on quality because of this decision. I call that a success.