Tonight the winner of the 2019 Man Booker International prize will be announced, and it’s something of a landmark year for women in translation. I want to talk about how 2018’s Year of Publishing Women, though it seemed to have a relatively small reach at the time, has had a significant impact on this prize: it’s possible that we’re witnessing a coincidence on a grand scale, but perhaps the fact that the shortlist features a higher proportion of women than is usual for literary prizes is a direct consequence of the Year of Publishing Women – partly owing to what was published last year, but also because of an increased awareness of the importance of striving for greater balance. The gender ratio on this year’s shortlist has made headlines everywhere, but even in neutral reports an unconscious bias is evident; in The Guardian it was described as being “dominated” by women, a phrasing quite rightly questioned by women in translation advocate Meytal Radzinski. Her point was that no shortlist with the opposite ratio would be described as being “dominated” by men – that would just be normal, right?

Right. Except it’s so wrong that this attitude of male “domination” being normal is still prevalent. I’ve encountered several people in the past year who have said they’re unsure about whether there should be such a thing as a year of publishing only women, and so I’m just going to nail my colours to the mast and say that at this point in history YES, THERE SHOULD: women are disadvantaged at every stage of the publishing process, and this is compounded in translated literature as women face a double marginalisation. By not challenging this, we allow it to continue. Saying that we’re not gender-biased but still having catalogues or bookshelves that are heavily weighted towards male authors is, I think, quite dangerous: there may not be conscious bias, but the bias that exists at all the stages a book goes through on its journey to translation, publication and reception is allowed to continue – is even normalised – if we ignore it by believing that not being deliberately biased against women in translation is enough to tilt the balance.

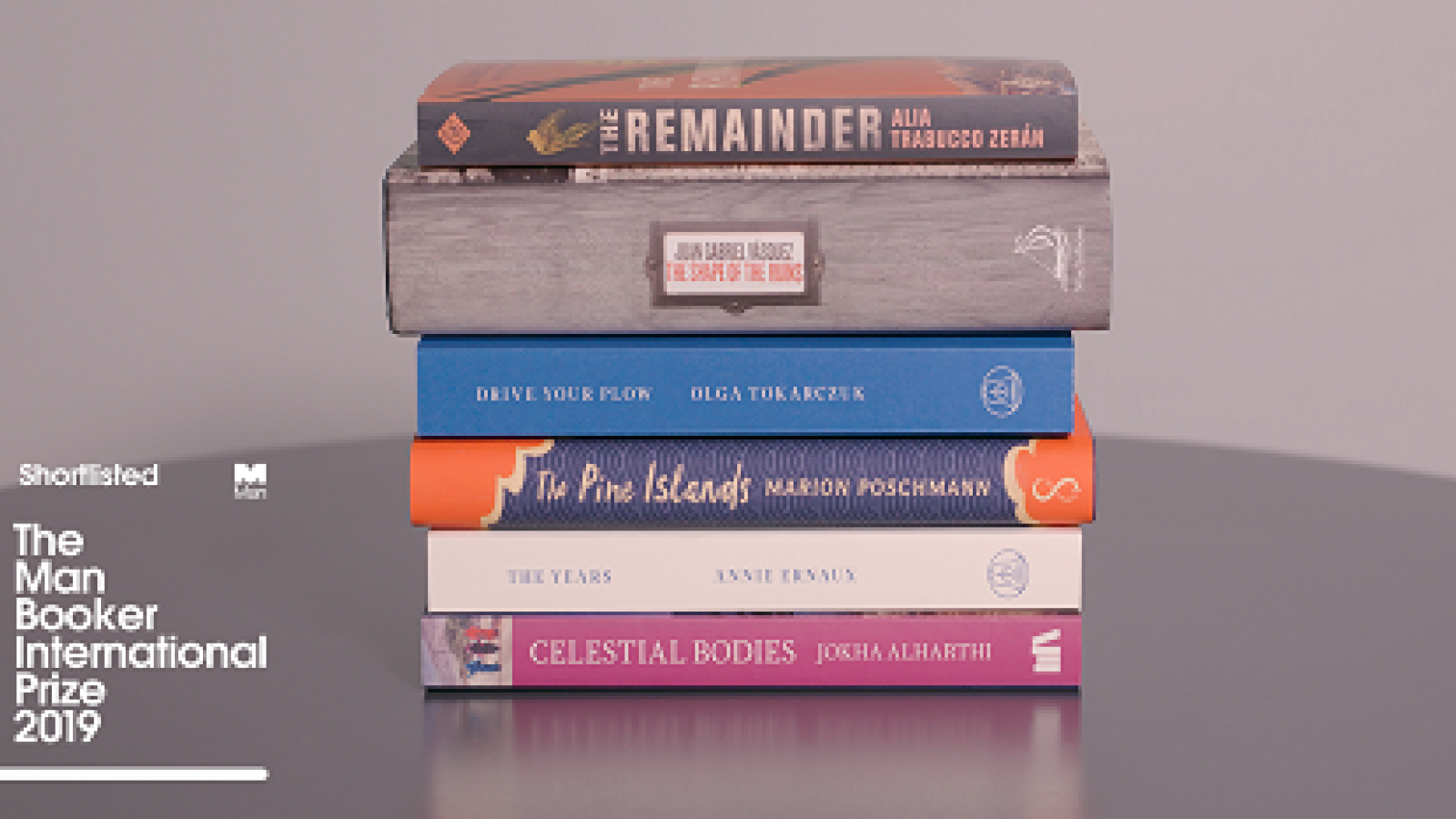

So the Year of Publishing Women was brave and necessary, and opened a dialogue about the books that get published and those that don’t. In an interview last year, publicist Nicky Smalley told me that And Other Stories (the only publishing house to commit fully to the Year of Publishing Women) had to actively seek out books by women writers to fill the 2018 catalogue; one of those books, Alia Trabucco Zerán’s debut novel The Remainder, is now on the Man Booker International shortlist. The Remainder is a spirited dual narrative in which three young people shackled to the historical memory of the Chilean dictatorship drive a hearse through the mountains from Chile to Argentina in search of a corpse lost in transit, and was beautifully translated by Sophie Hughes for And Other Stories. Its well-deserved place on the shortlist represents activism at its best, and it is not the only success of the Year of Publishing Women: the more women are published, the more they will be discussed, reviewed and entered for prizes, and the more these lists might see a more lasting shift where people are no longer surprised to see the scales tipped towards a preponderance of women writers. Where this is no longer “unprecedented”, no longer a surprising “domination”, but something perfectly normal – just as it will continue be perfectly normal for the ratio to favour men on other occasions. Neither scenario should be surprising, and yet one of them is.

The 2019 Man Booker International shortlist also smashes tired stereotypes of what women write about: women’s writing is too often pigeonholed as “romance”, “chick lit” or “women’s fiction”, and it is assumed and accepted that women write for women (an attitude brilliantly challenged by Rhiannon Lucy Cosslett) – these kinds of facile assumptions are exactly what perpetuate the invisible bias that women writers have to confront every time they sit down to write. And yet the women-authored books on the Man Booker International shortlist are extremely diverse: as well as Trabucco Zerán’s debut novel, there is the second English-language publication of last year’s winner, Olga Tokarczuk: the magnificent Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead is a witty and poignant pseudo-noir murder mystery flawlessly translated by Antonia Lloyd Jones for Fitzcarraldo Editions. The difference in genre and voice from Flights (Tokarczuk’s 2018 prizewinner, translated by Jennifer Croft for Fitzcarraldo Editions), along with the sheer scope of her work, shows that we cannot pigeonhole Tokarczuk (and, with her, Polish literature or women’s writing). And the excellent, ambitious books are not limited to The Remainder and Drive Your Plow (though they are my two unequivocal favourites on the shortlist): in Celestial Bodies Jokha Alharthi tells the history of Oman through the women of one fictional family, translated by Marilyn Booth for Sandstone Press; Annie Ernaux’s The Years is a “collective autobiography” of twentieth-century French cultural history, translated by Alison L. Strayer for Fitzcarraldo Editions, and Marion Poschmann’s The Pine Islands, an excoriating account of one man’s self-indulgent journey of enlightenment, finds new audiences in Jen Calleja’s sardonic translation for Serpent’s Tail.

Women represent half of history, half of the world, half of life – let them fill half your bookshelf, and then we won’t need a Year of Publishing Women or see women’s success framed in terms of anomalous “domination”. I’ve mentioned the scales tipping, the balance shifting, the ratios changing: the theme for International Women’s Day this year was “Balance for Better”, and I believe that the Year of Publishing Women has done exactly that. Shamsie noted that the real point of interest would be what happened in 2019:

“Will we revert to the status quo or will a year of a radically transformed publishing landscape change our expectations of what is normal and our preconceptions of what is unchangeable?”

2018 may not quite have been the “radically transformed publishing landscape” that Shamsie had hoped for, but the Year of Publishing Women did shake up expectations, complacencies, and resignation about the “unchangeability” of gender bias. The 2019 Man Booker International shortlist is testament to that, and as both gatekeepers and readers we need to carry on balancing for better so that the legacy of the Year of Publishing Women is not limited to one year, but carries on challenging the status quo until the status quo itself is changed.