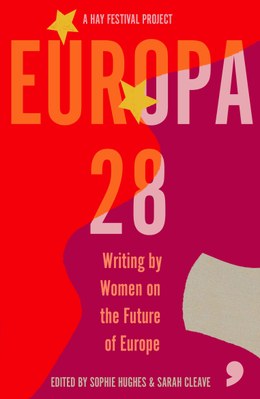

Edited by Sophie Hughes and Sarah Cleave (Comma Press, 2020)

Europa28 is a ground-breaking anthology of women’s voices from across Europe, commissioned in response to the UK’s decision to leave the European Union. Bringing together reflections on Europe’s future from women in each of the 28 member countries (or, as things stand now, 27 plus one), it reflects the radical, engaged approach that Comma Press is known for, and is Comma’s first anthology written entirely by women. Europa28 is a visionary project, the strength of 28 voices – plus 16 translators, two editors, and the indefatigable team at Comma Press, along with their collaborators Hay Festival and Wom@rts – coming together to discuss Europe in all its diversity, complexity, beauty and fallibility.

In her impassioned introduction to the volume, Laura Bates explains the importance of hearing the perspective of women: according to analysis cited by Bates, 90% of the discussion of Brexit in the Houses of Parliament was carried out by men. Women were left out of the debate, leaving “the certainties presented by the loudest voices” to remain enshrined as fact. “To move forward”, writes Bates, “we need new ways of seeing the world around us”, and this is exactly what Europa28 offers. There is, of course, a potential danger in selecting one woman to represent each country, but to be less even-handed about the representation would generate its own problematic hierarchies. And so while one voice cannot and should not speak for an entire country (indeed, this is a position challenged by the Europa28 project), more important is that this collection offers the space to speak, setting the perspectives of all 28 women – and the nations they represent – in dialogue with one another. It brings spoken-over voices to the fore, challenging the “default setting” of seeing the world through men’s eyes and gathering together women’s perspectives from each country within a union that, though imperfect, until recently represented our closest ally.

In her impassioned introduction to the volume, Laura Bates explains the importance of hearing the perspective of women: according to analysis cited by Bates, 90% of the discussion of Brexit in the Houses of Parliament was carried out by men. Women were left out of the debate, leaving “the certainties presented by the loudest voices” to remain enshrined as fact. “To move forward”, writes Bates, “we need new ways of seeing the world around us”, and this is exactly what Europa28 offers. There is, of course, a potential danger in selecting one woman to represent each country, but to be less even-handed about the representation would generate its own problematic hierarchies. And so while one voice cannot and should not speak for an entire country (indeed, this is a position challenged by the Europa28 project), more important is that this collection offers the space to speak, setting the perspectives of all 28 women – and the nations they represent – in dialogue with one another. It brings spoken-over voices to the fore, challenging the “default setting” of seeing the world through men’s eyes and gathering together women’s perspectives from each country within a union that, though imperfect, until recently represented our closest ally.

Editors Sophie Hughes and Sarah Cleave have brought together a fascinating and diverse collection of expositions on what Europe can, could, or should mean. Some of the contributions are reflections based on personal experience or perspective, while others are fantastical or allegorical. Some are essays, some written from an imagined future, some struggling to find the light ahead while mired in an all-too-present now. There are profound reflections on humanity, from Apolena Rychlíková’s claim (translated by Julia Sherwood) that intolerance is not buried deep in human nature but is the mindset of powerful individuals, to Janne Teller’s pronouncement that “no happiness is possible where misery abounds.” Many pieces focus on what Edurne Portela (translated by Annie McDermott) defines as “the demonisation of the different”; surveillance, silencing and “fake news” also come under fire repeatedly, as does the complicity of silence and the danger of becoming so immersed in the virtual world that we risk sacrificing our relationships with one another.

Where did these problems, barriers and divisions spring from? Rychlíková believes them to be the result of “a boiling over of long-term frustrations for unfulfilled, even if unarticulated, demands for a dignified and well-rounded life,” while Maarja Kangro points to “a new norm of ignorance, intolerance, and exclusion”, which Yvonne Hofstetter (translated by Jen Calleja) expands on in her claim that “reality is currently taking a detour through populism, protectionism, nationalism and a good dose of arrogance.” Tereza Nvotová (translated by Jakub Tlolka) suggests that we have not learned from our past (“We scale the cold neon mast and then drop back down, again and again and again. But each time we climb to the top, we forget about our previous fall”), a position advanced by Gloria Wekker, who cites “the bitter continuities and the utter lack of shame manifesting in European political attitudes towards the non-European Other” as one of the problems within the continent and the union.

The very notion of “union” is another key focus for many of the writers, who highlight the increasing disconnectedness of our – ironically – ever more connected world. Žydrūnė Vitaitė (translated by Rimas Uzgiris) cautions against the “like and re-share cemetery” of digital activism as opposed to real activism, and from a different angle Caroline Muscat warns that this digital world that we welcome as liberating can in fact be used to control us, making us complicit in the problem: “Technology fed into this populism as digital platforms – which held so much democratic promise for opening up access to information and debate across communities and countries – ended up being used as tools of repression.” If our increasing disenfranchisement is so widespread, then it is surely no coincidence that Ana Pessoa (translated by Rahul Bery) describes loneliness as “the biggest epidemic of the 21st century”: in our obsession with being “connected,” we have lost sight of what we want to connect to. To counter this, Hilary Cottam urges us to leave old models behind and “start instead with who we really are: people who are driven as much by a desire to connect and belong as by our individual goals.”

Cottam is not the only one to propose ways of moving forward, and of working towards greater understanding and deeper connections: the ability for empathy, suggests Julia Rabinowich (translated by Katy Derbyshire), “is what might help humankind survive.” Like Nvotová, Kapka Kassabova implores us to “hear the urgent message of the past” and refuse to let the past – with all its errors and misunderstandings – endlessly repeat itself, for as Ioana Nicolaie (translated by Jean Harris) warns: “If we do not learn from the mistakes of the last century, we will find ourselves alone without freedom or hope, enclosed between walls we ourselves have allowed to be built.” The possibility for change lies in our own hands, say so many of these women: we need to break through the walls we have allowed to be built and create what Lisa Dwan refers to as “a different narrative, to overcome the oppressive voices that threaten us from without and from within.”

Many of the contributions, then, suggest what we need to do to reject structures that restrict and oppress us, but others go further still to offer models of how we might set this in motion. Leïla Slimani (translated by Sam Taylor) exhorts us to be more open to others, indicating that prejudices surrounding migration could be at the root of a damaging isolation: “still today, the question of migration is fundamental, central, because the future of our continent will be decided in terms of our capacity to welcome and also to think about the Other.” Tuning out the certainties presented by the loudest voices is essential here, and Sofía Kouvelaki encourages us to do this by looking up from ourselves and outwards towards our world: “I simply want to ask people not to look away, not to look away and remain passive about the violence that is also taking place on our doorstep as Europeans.” This commitment to making connections involves us looking up and reaching out: Hofstetter advocates for exactly this in her provocation for each of us to “breathe life back into Europe, build a better future and live humanely and democratically with others.” Reading Europa28 is a fitting place to start this engagement: throughout the anthology, the personal and the local are cast as inseparable from the collective and the global, with an emphasis on sharing stories as a key to mutual understanding and tolerance. As Annelies Beck notes, “stories … can unlock hearts and minds and lay bare the shared humanity of all … They can put a wedge in shrill sounding certainties that are sold as unassailable truths.” It is important to listen to diverse stories, to understand the fullness of humanity (and specifically, to return to a key point of my last post, the “full humanity of women”), and to topple inherited or self-perpetuating certainties that threaten not only our sense of where we belong, but of who we are. As Europa28 shows us throughout, we do not need to rely on a nostalgia for what we have lost, but instead think about what we want to become.

Review copy of Europa28 provided by Comma Press.