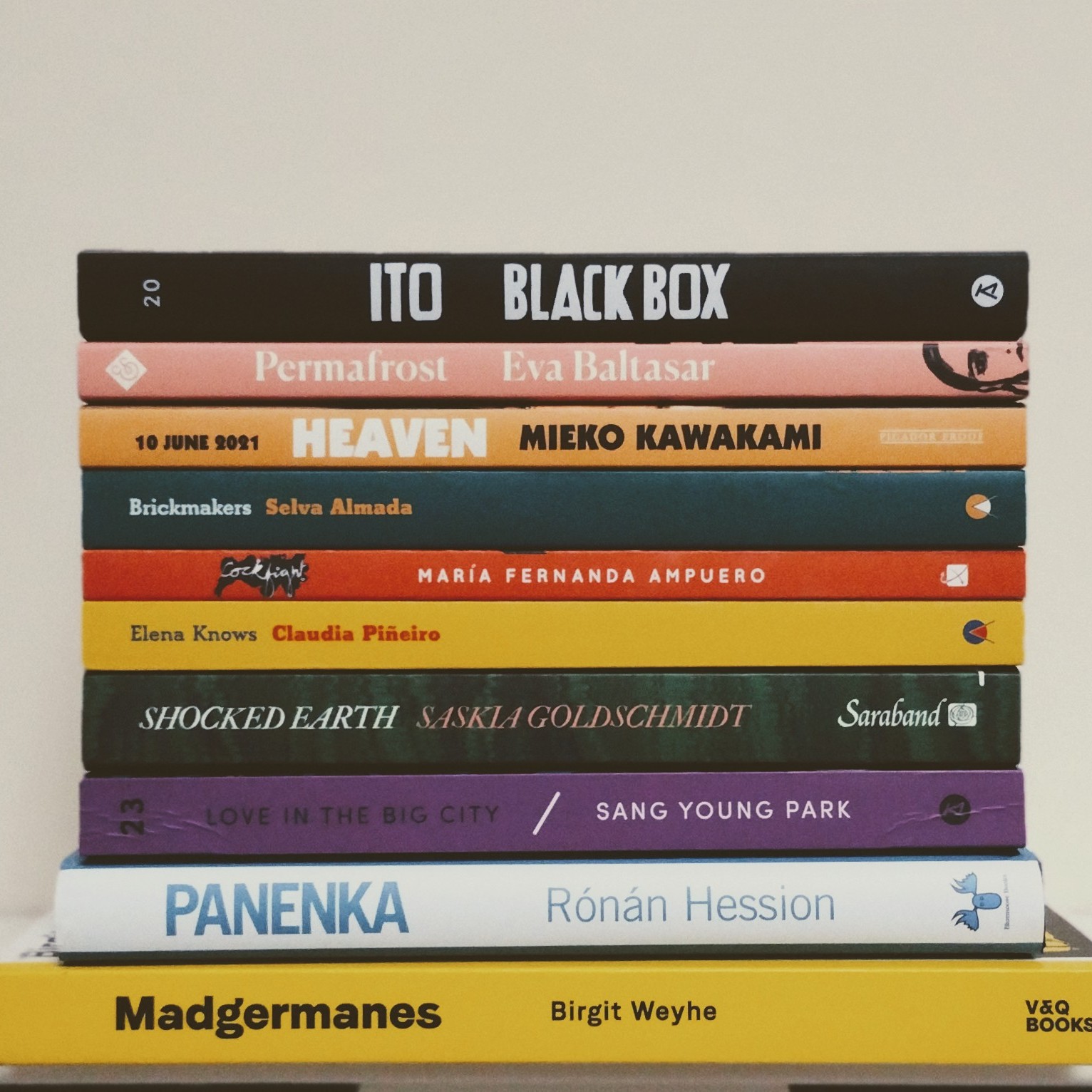

When I wrote my round-up of 2020, I had no idea that 2021 would be another year of restrictions and adaptations. I haven’t read as much as I’d have liked to this year, and I leave 2021 with several unread or awaiting review. But of those I have read, I wanted to bring you my now-traditional end-of-year highlights, so here are the ten books that most moved or delighted me in 2021.

María Fernanda Ampuero, Cockfight, tr. Frances Riddle (Influx Press)

The first book I read this year, Cockfight set the bar high for my reading in 2021. The debut work by Ecuadorian writer and journalist María Fernanda Ampuero comprises thirteen brutal and brilliant short stories: with subject matter and descriptions that range from mildly uncomfortable to outright terrifying, these stories are disturbing and unsettling, populated by women who are prisoners in their homes and lives. No airbrushed, sanitised view of womanhood is offered, no false agency given to characters who live in fear not just of what lies in wait for them outside their homes, but also within its walls. A startlingly brilliant collection in an appropriately merciless translation, but not for the faint of heart!

Eva Baltasar, Permafrost, tr, Julia Sanches (And Other Stories)

In November 2019 (which feels like a lifetime away) I was in Barcelona with my husband and we bought a new novel called Permagel. My Catalan isn’t good enough to struggle beyond a few (glittering) pages, but my husband read it and told me it was outstanding. So imagine my joy when And Other Stories published it in a translation by Julia Sanches… Permafrost is narrated by a young lesbian teetering on a rooftop, reflecting on all that pulls her back to life and all the reasons she has for falling away from it. Poetic and intense, this debut novel explores sex, desire, freedom and death, and has a twist at the end that knocked me sideways. This exquisite novel has had a relatively quiet reception, and deserves to be shouted about.

Rónán Hession, Panenka (Bluemoose Books)

No, it’s not a translation. No, it’s not written by a woman. But it’s a very special book from a very special writer. The heart of the novel is Joseph, a former footballer whose nickname “Panenka” is “his sadness and his story.” Diagnosed with a terminal illness, Panenka carries on with what he has made of his rather unspectacular life, renewing fragile bonds and creating bittersweet new ones. Chock-full of perfectly observed dialogue and believably imperfect characters, this is a small town novel with a great big heart and a final scene that (unless your heart is more hardened than mine) will make you weep.

Saskia Goldschmidt, Shocked Earth, tr. Antoinette Fawcett (Saraband Books)

Back in May I went out on a limb and declared that Shocked Earth would be one of my favourite books of 2021. It’s entirely the quality of the book and not my desire to be proven right that still maintains this as the year draws to a close! Shocked Earth is the story of three generations of the Koridons, a farming family in Groningen province. There is intrigue in the form of generational conflict as well an ever-present threat in the form of quake damage caused by gas extraction: the government has realised that it can make a significant profit from gas that has been discovered beneath the clay lands, yet refuses to acknowledge – let alone compensate – the damage to lives and livelihoods caused by its actions. This is a book that is simultaneously about big issues and everyday people, and in which profound truths appear when you least expect them.

Mieko Kawakami, Heaven, tr. Sam Bett and David Boyd (Picador Books)

Heaven was one of my most anticipated books this year, and it did not disappoint. A spare yet complex portrayal of teenage bullying, Heaven is told from the perspective of a an unnamed male narrator with a lazy eye who is subjected to horrific physical and psychological torment from a group of boys in his class. He strikes up a friendship with Kojima, a girl who is also bullied at school, and in whom he finds a kindred spirit, a friend in need, and someone who finally understands both what he suffers and why he does not fight back. Kawakami does not shy away from the cruelty that human beings are capable of inflicting on one another, and nor does she offer any crass kind of redemption in which the bullies realise the error of their ways. Heaven is a truly wonderful book: discomfiting, unsettling, and entirely unique.

Claudia Piñeiro, Elena Knows, tr. Frances Riddle (Charco Press)

Elena Knows is Charco’s first publication by Argentinian crime writer Claudia Piñeiro, and follows a single (and very long) day in the life of protagonist Elena as she treks across Buenos Aires in search of help solving the mystery of her daughter Rita’s death. Rita had been found hanging from the belfry of her local church, and the case has been closed as a straightforward suicide. But Elena knows that it couldn’t have been suicide, because it was raining on the day of Rita’s death and Rita was deeply superstitious about never going to church in the rain. This fact, dismissed by the police, is one of many things that Elena knows, yet everything that she is so certain of will become destabilised in the course of the narrative, as Elena learns painful truths about her daughter, and realises how much she doesn’t know. Elena Knows is a murder mystery, yes, but also an unflinching exploration of aging and illness, of the Catholic church and the way it uses its influence in Argentina, and of the multiple ways women’s bodies are controlled.

Shiori Ito, Black Box, tr. Allison Markin Powell (Tilted Axis Press)

I was interested to read this journalistic exposé about rape culture in Japan, but was not expecting to be drawn into it on such a personal level. Though Ito reports the case of her sexual assault by a powerful man with as much objectivity as possible, she also creates a gripping and horrifying personal story that blows the lid off the multiple ways in which women in Japan are restricted and silenced. The horrific details of her rape by a man who spiked her drink during a dinner she thought was a business meeting come to light slowly, as Ito makes her way through the fog of amnesia that the date rape drug caused. When she realises what has happened, she embarks on a long and exhausting legal struggle to seek justice for what she has endured, but is frustrated and abandoned at almost every turn by a corrupt legal system and relatives who wish she would stay silent. It’s not often that I say people “should” read a book, but this one is the exception.

Birgit Weyhe, Madgermanes, tr. Katy Derbyshire (V&Q Books)

Graphic novels aren’t usually something that appeals to me, but Madgermanes caught me by surprise. The Madgermanes of the title are Mozambican workers once contracted out to East Germany; they lost their residency status after the fall of the Berlin Wall and had to return to a place that no longer felt like home, their wages having disappeared into the ether. Birgit Weyhe conducted extensive interviews with some of these workers, and from their stories created three fictional narrators who each revisit the same period of their shared past, their paths and emotions tangled but their futures devastatingly separate. Madgermanes offers a unique perspective into a group of people forgotten by every place they have called home, and let down by every institution that promised them a better life. The combination of words and images is incredibly moving, and has much to teach those of us who, like me, knew nothing of the Madgermanes before now.

Sang Young Park, Love in the Big City, tr. Anton Hur (Tilted Axis Press)

Sang Young Park’s novel about a young Korean searching for love and for a meaning to life and to his relationships with men is quite simply one of the most beautiful, painful, joyful things I’ve read. I read the entire thing in a day (in fairness, a day when I spent a lot of time on a train, but still…) and it was glorious. The protagonist, Young, dances his way through glittering late-night Seoul and drags himself through the bleary-eyed early mornings as he navigates friendship, benders, emotional distance and the truest love of all. Steeped in popular culture and its contingent highs and lows, this is an unmissable story of (self)love (with a fantastic cover design whose meaning will swiftly become apparent), in a sublime translation by Anton Hur.

Selva Almada, Brickmakers, tr. Annie McDermott (Charco Press)

It’s only a week since I was waxing lyrical about Brickmakers: if it’s possible to describe a 200-page novel as epic, then this is the one. The narrative opens with two young men lying close to death in an amusement park: rivals in a multi-generational family conflict, Pájaro and Marciano have grown up in a small and scorched town where “all anyone knows is violence and force”: as we meet them they have each avenged their family’s honour in a knife fight, and are now bleeding to death as a result. Machismo leaks from the pages, with disappointing men shirking their responsibilities and abandoning wives who keep trying to hold their broken families together as best they can. The storytelling is superb, the characters perfectly flawed, and the vision as sweeping and sizzling as the sun-scorched plains the families inhabit.