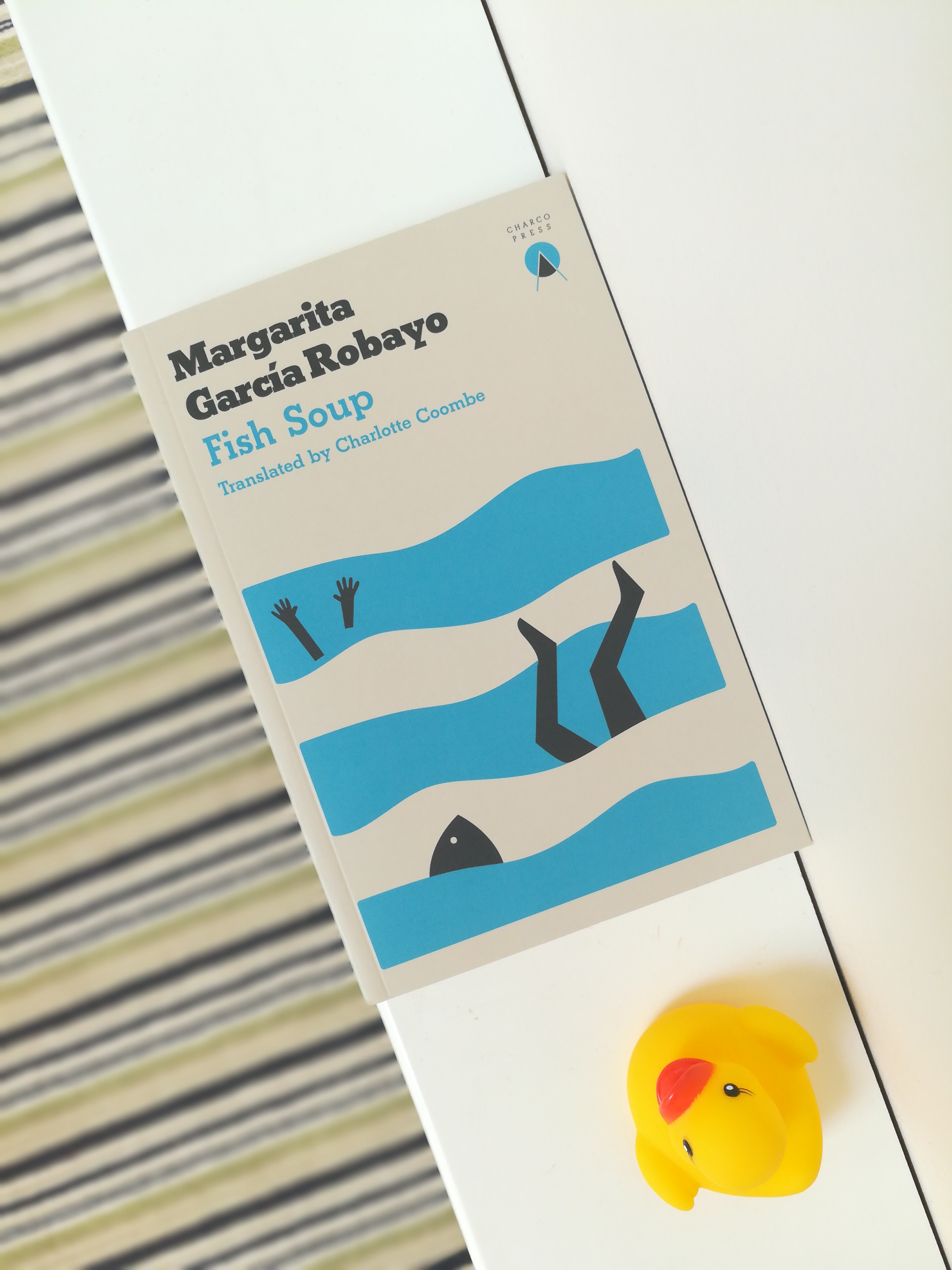

Translated from the Spanish by Charlotte Coombe (Charco Press, 2018)

Fish Soup is one of my favourite discoveries of 2018: in it, Charco Press brings together a collection of novellas and short stories by Colombian author Margarita García Robayo, superbly translated by Charlotte Coombe. The three sections of Fish Soup are, in order of appearance, the novella “Waiting for a Hurricane”, whose narrator despises her home and is increasingly desperate to leave, the collection of short stories “Worse Things”, snapshots of disintegrating families and bodies which won the prestigious Casa de las Américas prize in 2014, and the novella “Sexual Education”, a bitingly hilarious account of sex education at a Catholic girls’ school in 1990s Colombia, which has not yet been published in Spanish.

García Robayo writes with brutal candour, creating strong female characters determined to take control of their bodies but corseted in the norms of a society they reject yet cannot escape. “Waiting for a Hurricane” is recounted by an unnamed narrator, growing up near the sea and longing to move away. She is dismissive of her family and wants something different for her own future: “I was not like them […] at the age of seven I already knew that I would leave. […] When people asked me, what do you want to be when you grow up? I’d reply: a foreigner.” This longing to be elsewhere pervades the narrative, blinding the narrator – or at least leaving her insensitive – to the way in which she is hurting the people who care about her as she pushes single-mindedly towards her goal. She has several lovers in the course of her story: firstly, there is a mildly disturbing relationship as an adolescent with ageing raconteur fisherman Gustavo, then her first boyfriend Tony, who adores her but from whom she is implacably detached both emotionally and sexually (“I put my hands behind the back of my neck, as if I was doing sit-ups, and waited for Tony to finish”). Tony wants to marry her, but all she sees is a horizon before her, and everything becomes about escaping: “Tony had a lot of ideas about air hostesses, but I had just one: air hostesses could leave.” With this realisation, she becomes an air hostess, and is then courted by “the Captain”, who cannot give her what she wants, for though he offers a comfortable life and a fabulous apartment, “it was very beautiful, but it was still here.” Then, when she finally realises her dream of escaping, she meets Johnny (real name Juan), a larger-than-life (and married) wheeler-dealer gringo living in Miami, who eventually becomes the latest casualty in a sequence of losing people she “didn’t even care about.”

Coombe says of the first time she read “Waiting for a Hurricane” in Spanish that: “I automatically started translating in my head as I was reading. For me this is always a good sign with any book I read in another language; it means I can hear the voice, I relate to it and I am simply itching to put it into English.” This connection between translator and text is evident: the translation is pitch-perfect, and Coombe has an incredible ear for García Robayo’s characters (there are only two minor details in over 200 pages that I could even start to criticise). Coombe has embraced the outrageously crude tone of García Robayo’s writing and communicated it in all its visceral glory, not only in “Waiting for a Hurricane”, but throughout the volume. The seven short stories in “Worse Things” are peopled with characters who, as Ellen Jones notes, are “plagued by apathy and disaffection”: from the physical description of an ageing ladies’ man (“Leonardo was balding, and sweat accumulated each side of his widow’s peak, out of reach of the handkerchief he used to wipe his face every so often”) to the summing up of a suffering aunt’s unremitting averageness (“She was neither ugly nor pretty. And, as far as Ema could recall, neither was she good at anything in particular. She was utterly unremarkable”) and the relentless resignation of a morbidly obese teenager’s mother (“She thought it was better not to make things more complicated than they were; this was what life had given them, and things were fine. Relatively fine. What could be worse? So many things. There were worse things”), García Robayo’s sparing prose offers a piercing insight into characters brimming with abjection, fury, and disgust for themselves and their lives.

Sex in “Worse Things” (and throughout Fish Soup) is never tender or emotional, but savage, detached, or barely enjoyable. In some cases it is revolting even when consensual: “Leonardo plunged his fingers in and out as if he were unclogging a drain; he jerked himself off with his other hand. He came with a loud moan, and slumped forward onto Inés, smearing his own semen under him.” In others, it is a simple transaction or perfunctory act: “she went down between his legs and sucked him off like she’d never done before”. Characters are either physically repulsive or emotionally repellent, their bodily fluids grotesque and free-flowing. But this is not just to make you shudder or grimace: in the marvellous “Sky and Poplars”, García Robayo uses an abject expulsion of breastmilk to reveal one of the most harrowing experiences of the collection.

Bodily abjection and unpleasant sexual encounters lead into the final novella in the collection, “Sexual Education”, in which a group of senior year girls at a Catholic school are subjected to an abstinence programme designed to combat the proliferation of unwanted pregnancies, with the result that “we spent a good part of our final year listening to Olga Luz prattling on about the virtues of the hymen and the unspeakable dangers of semen.” Sexual acts are at no point redeemed as enjoyable or desirable: when the narrator witnesses a moment of intimacy between her friend and her boyfriend, she explains how her friend “pushed Mauricio’s head down and he went under her skirt and held her thighs open with his hands. I could hear what sounded like a dog licking something.”

Yes, it makes you squirm. But there are also moments of great hilarity, such as the way the narrator dismisses her friend Karina, who regularly converses with the Virgin Mary, when she explains that the Virgin has instructed her that as long as the hymen is “safeguarded”, the girls may make love with other parts of their body, resulting in a generation of girls with “hymen intact, ass in tatters.” This is a pitiless narrator, and no-one emerges from her observations unscathed, not even herself. In fact, she has a self-awareness that made me chuckle: when forced to attend a party, she dresses “as if I couldn’t give a flying fuck about the party or the people there, which meant I had spent hours trying on different outfits in front of the mirror.” These adolescent concerns are offset by darker episodes such as a horrific gang rape, and showcase García Robayo’s merciless exposure of a society where women have no agency.

The narrator’s uncompromising disdain for those around her is counterbalanced by the one time that she lets herself get carried away by instinctive emotion when she sees a boy at the party, and in an instant imagines their future, sailing away together into an improbably perfect sunset. Unwittingly, she has fallen for her friend’s new boyfriend, as she discovers when the friend appears and sits down on his lap, drawing a barrier between the narrator and her projected future: “Next thing I knew, burning rocks came raining down on our boat, just a few miles off Cadiz. We exploded into a gazillion pieces that momentarily blinded me, and then vanished into thin air, like a foolish hope.” The usually sardonic narrator experiences a pang of desire and loss that, as with the narrator of “Waiting for a Hurricane”, makes our awareness of her youth painfully acute.

García Robayo’s great talent is for presenting tragedy with mordant humour, and with Coombe unafraid to replicate the crude and caustic language, the result is a rollicking, darkly funny, occasionally disturbing, and delightfully uncomfortable collection that deserves to be widely read.

Charco are offering 15% off all women in translation titles until the end of August 2018: just enter the code #WITMONTH at checkout!

Review copy provided by Charco Press.