CREATOR/S: Bill Bergeron

YEAR: 1973

PLACE: Chicago

PUBLISHER: Chicago Review Press

ORIGINAL PRICE: $1.95

PRINT RUN: Not known

WHERE CAN I READ IT FOR MYSELF? The British Library

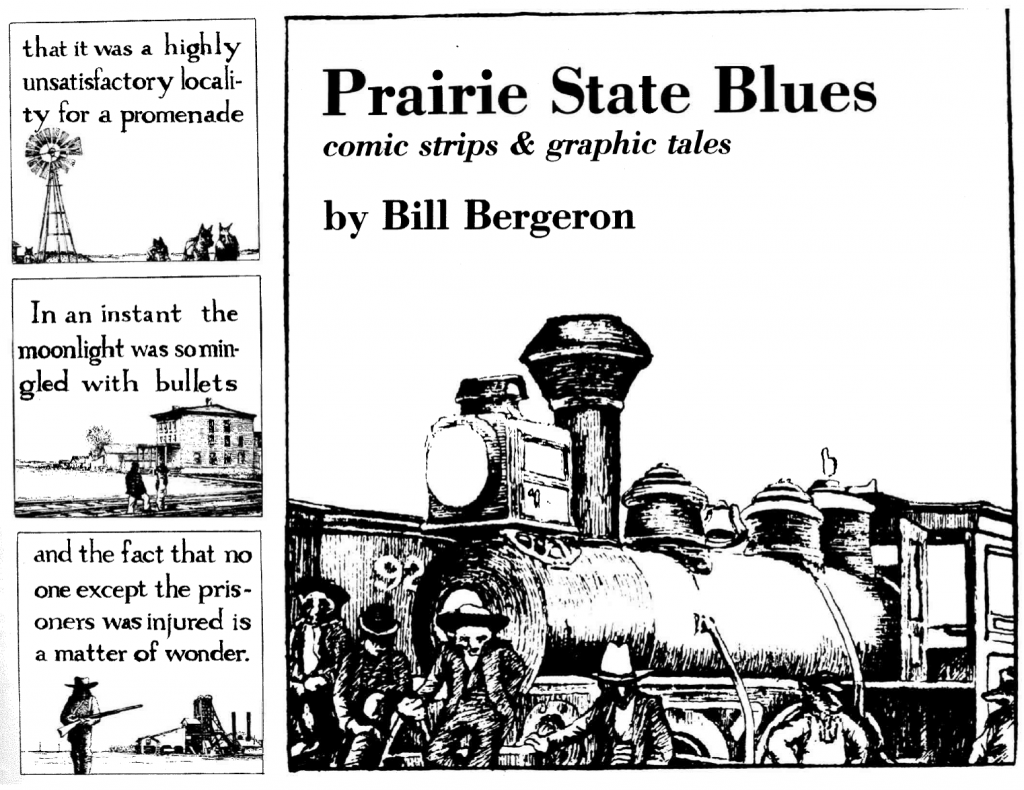

Prairie State Blues: Comic Strips & Graphic Tales (1973) is a collection of comics from very different genres, from illustrated historical reports and blues lyrics to violent dreams and ‘funny animal’ stories. It is one of the rarer books of comics from the 1970s, as a quick search of online retailers and auction sites will attest.

Prairie State Blues stands out for several reasons: first, it is presented in landscape style, measuring 8 ½ inches high and 11 inches wide; second, it was one of the first books published by Chicago Review Press, not a publisher renowned for their comics output;[i] third, before Prairie State Blues there had been few single-creator book collections to come out of the underground, so it is even more surprising that an obscure writer and artist such as Bergeron has a book dedicated to his work. Information about Prairie State Blues is hard to come by; the entry on Bergeron’s book in Jay Kennedy’s The Official Underground and Newave Comix Price Guide (1982) notes it was meant to be L.A. Comics 3, which I have been unable to corroborate, but the swearing and hard-drinking animal characters place Prairie State Blues solidly in the context of the underground.

Given that Prairie State Blues brings together very different genres of comics it may seem a perverse choice for the first posting on a blog about 1970s graphic novels. The critics who reviewed Bergeron’s book when it came out did not see it as a novel: in the December 1973 Comix World Clay Geerdes called it “[i]llustrated poetry.”[ii] The contents page of Prairie State Blues refers to untitled sections by using the first line of each text as its title, a convention used in anthologies to identify unnamed poems. I’m going to suggest we can think about Bergeron’s book as a novel, and as you may have guessed, this blog is going to take a fairly stretched approach to definitions. I have no difficulty seeing John Dos Passos’s U.S.A. (1930-36) or Julian Barnes’s A History of the World in 10 ½ Chapters (1989) as novels, and in modernist and postmodernist texts such as these the convention of following a character or characters across a period of time has been jarringly fractured. Of course, telling a story always involves selection, editing and rearrangement of material, and sometimes jumping forward and backwards in time, but Dos Passos’s and Barnes’s novels are especially fragmented, demanding dexterous reading to see connections between sections. And yet these books do possess a degree of novelistic unity, afforded through the repetition of place, symbol and theme. In The Composite Novel: The Short Story Cycle in Transition (1995) the critics Maggie Dunn and Ann Morris use the term “composite novel”[iii] to describe a literary text “composed of shorter texts that – though individually complete and autonomous – are interrelated in a coherent whole according to one or more organizing principles” (2). The organizing principles Dunn and Morris list include a shared setting, a recurring single protagonist, a collective protagonist (perhaps a generation or a family), repeated story patterns or motifs, and finally, collections where the very act of telling each story supplies the connective tissue holding the disparate elements together (14-16).

Dunn and Morris’s subtitle indicates that they are advancing ‘composite novel’ as an alternative to the more common term used for such collections: the ‘short story cycle,’ a coinage going back to Forrest L. Ingram’s Representative Short Story Cycles of the Twentieth Century: Studies in a Literary Genre (1971). This popular term is questioned by one of its most important critics, J. Gerald Kennedy, who deploys ‘short story sequence’ to sidestep the sense of contained circularity that the word ‘cycle’ implies (“Definitions” xv n. 3). Kennedy shows how Ingram took “for granted the formal unity of the story sequence” (ix), seeing it as an integral whole, something that Ingram’s scholarly successors have been tempted to do as well. Kennedy’s influential approach is to counterbalance the text’s commonalities by emphasizing its “discontinuities,” seeing those “gaps” and “rifts” as the preferred highway “into the cultural significance of the form” at particular historical moments (“From” 196-97). I’ll use Dunn and Morris’s definition here, which avoids the association of circularity and includes non-short-story material (3-7), but I want to make an amendment: rather than take for granted the cohesiveness implied by Dunn and Morris’s “shorter texts […] interrelated in a coherent whole” (2), I want to follow J. Gerald Kennedy and see the composite novel as something tantalizingly incomplete, a text to be studied as an incoherent whole.

The comics in Prairie State Blues can be loosely grouped as follows: funny animal stories, illustrated extracts from historical records, and stories featuring the dreams and wordplay of a male narrator who grew up in the ‘Prairie State’ Illinois and who now resides in California. They are not clustered together like this in the book, a comic from one of these categories is always followed by one from a different genre (with a solitary possible exception). The final three comics in Prairie State Blues do not fit into any of those categories, but this last trio of texts echo several elements running through the book: the motif of the snake; the intertwinement of romantic conquest and self-image; sickness, death, violence and the precariousness of human existence; and the friction generated between the human desire to project meaning and a recalcitrant natural world that resists sublimation into human terms.

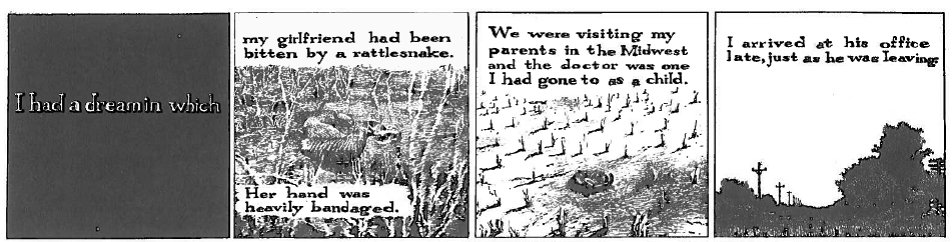

The persona of the Illinoisan exiled in California is close to Bergeron’s biographical context. The back of Prairie State Blues records that the creator was born in 1938 “and raised in Illinois where he was a railroad fireman for five years. For the past ten years he has lived in Southern California.” The comics from this category establish the plains of Illinois and the Midwest more generally as sites of great solitude and physical beauty that have an inescapable hold on the people who live there. Even when the ex-Illinoisan lives on the West Coast he is imaginatively drawn to the Prairie State, returning when he sleeps (“I had a dream in which” [see fig. 1]).

Fig. 1. Panels from “I had a dream in which,” Prairie State Blues. © Bill Bergeron 1971.

As with so many of the comics in Prairie State Blues, the recitative (the verbal commentary)[iv] is accompanied by images of Illinois’s flora and fauna, of cars, buildings and distant human figures (who are actually animals). The landscape jostles with the reciting character as the protagonist of the narrative. This pull of Illinois was registered in Geerdes’s review, praising Bergeron’s “[b]eautiful line work” for capturing “the atmosphere of the Midwest from trainyard to windmill,” and for making him “nostalgic for the plains where I grew up.” The comics with the reciter from Illinois are highly mixed in tone, at turns playful, at others frustrated. It is unclear who is speaking the first comic in the book, “I dreamt,” but it may be the same ex-Illinoisan; the dream is set in Lancaster, California, with a reciter who is “a long way from home.” Over two pages the reciter realizes his co-workers (exactly what work they do is not stated) intend to murder him in public view, and while he “feigned indifference […] I knew I was out of options, and my mouth tasted like ashes.”

The recitative is simple and clipped in “I dreamt,” reporting dialogue and impressions of the scene with little emotion or verbosity. This cool, detached, almost bored, attitude towards death (albeit one whose “indifference” is “feigned”) is apparent in the historical records Bergeron adapts into comics, “At 10:10 a.m.,” “A. J. Yarboro” and “Account.” These comics are all short (1-2 pages), the final panel of each one provides details of Bergeron’s sources, and they all decline to depict explicitly the violent or murderous events being recounted. These illustrated reports in Prairie State Blues exploit the disjuncture between the verbal telling of chilling events and the exquisitely detailed images of daily toil and the landscape. So “At 10:10 a.m.,” about a collision between a train and gasoline tank truck in Illinois in 1970, juxtaposes visions of tranquil scenery against a recitative taken from a forensic reconstruction of the terrible conflagration. These words seem to be at a remove from the inferno they describe, too restrained to do justice to the loss of life and the scale of the explosion. The report that Bergeron quotes from acknowledges its limitations, stating that it is impossible to know the cause of the accident since “all those riding in the cab of the locomotive were injured fatally.” As we saw in the story “I dreamt,” the stories in Prairie State Blues repeatedly try to imagine (one’s) death but struggle to follow this project to its conclusion.[v] We might say that with the illustrated reports Bergeron uses a technique designed to address this problem: avoid showing the recorded events in the monstration (what we are shown in a comic through non-verbal images).

There are no deaths in “A. J. Yarboro”… but only just. The eponymous protagonist is a law enforcement officer for the Game and Fresh Water Fish Commission, presumably in Florida. In the recitative Yarboro recollects an encounter with a resentful fisherman; the fisherman invited Yarboro to search his boat – having hidden a rattlesnake in a bag. The officer finds the snake before it can bite him, and the deadpan style of the report, the slow, unrushed ticking through belongings before the snake is discovered, stokes the sense that some sullen malevolence will be revealed before the comic concludes. Indeed, it is, but Bergeron’s underplayed approach diminishes the profundity of the murder plot. The monstrator never shows the boat’s search, and we do not seem to see the story’s two human participants; in the final panel the judgement passed on the fisherman seems meagre, “twenty dollars or twenty days.”

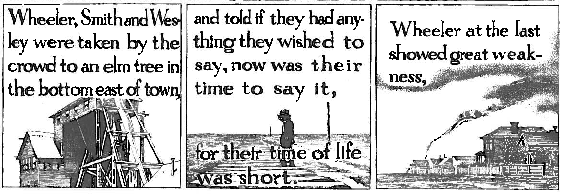

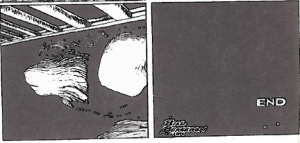

Fig. 2. Panels from “Account,” Prairie State Blues. Pictures © Bill Bergeron 1971.

“Account” reports the lynching of three robbers in Caldwell, Kansas in 1882. On first glance the monstration is full of clichés of turn-of-the-century rural America: a wire-fence across a prairie, a snowed-in cabin, men lounging proudly next to a locomotive and a drilling well. The penultimate panel depicts a horse-drawn wagon fording a river with the words “So ends the chapter.” Looking closer, those men are actually animals (see fig. 2). A quick glance might miss this, since Bergeron’s anthropomorphic animals are remarkably humanoid in bodily proportion, dressed in period clothes (including face-obscuring hats), and they are shown handling animals themselves. So we have snapshots of human lives from the past, set in the context of a recorded historical event, but the humans are visualized as dogs, badgers and other animals. Joseph Witek’s analysis of Art Spiegelman’s Maus (serialized 1980-91) springs to mind here. Witek differentiates Spiegelman’s “stylization of human beings as mice and cats” from the use of animal characters in fables, which are allegories derived from “well-established correspondences based on the natural attributes of species” (the tortoise’s association with patient perseverance, for example). For Witek Maus should be understood as drawing on “the traditions of ‘funny animal’ comics,” a tradition where the meanings attached to different animal species might “establish relations among the characters [but] the ‘animalness’ of the characters becomes vestigial or drops away entirely.” Beyond their immediate visual identity it is rare that ‘funny animal’ characters are marked as belonging to their supposed species: they are essentially humans. As Witek writes, Donald Duck cannot fly unless he gets in an airplane (102-114). Witek’s encapsulation of the ‘funny animal’ tradition seems appropriate to the anthropomorphic creatures in Prairie State Blues, since these characters speak and interact like humans sheaved in wolves’ (or other animals’) clothing, but they have a visual verisimilitude that troubles our reading of their status. This is apparent in the comics with the reciter from Illinois and in the illustrated historical records, but it is perhaps most obvious in the many comics in Prairie State Blues which are working in the underground permutation of the ‘funny animal’ tradition.

The ‘funny animal’ comics constitute the bulk of Prairie State Blues, not because of their quantity but because they are longer than the comics from other genres. Like many anthropomorphic creatures from underground comix, Bergeron’s animals swear, take drugs and are on the lookout for casual sex whenever it becomes available. Within Prairie State Blues there is a notable change between the earliest comics, copyrighted 1970, and the ones copyrighted later. The animal characters in those 1970 comics (i.e. “Ten Gears Forward, Tulsa’s Northward” and “Mound City”) are highly caricatured in a style reminiscent of the cartoons of Disney and Warner Bros. These earlier characters are also visually similar to the underground’s funny animals, like Robert Crumb’s Fritz the Cat or the animals of the Air Pirates collective. Bergeron’s funny animal characters from 1971-73, though, are noticeably different, depicted using sketchy, thin pen lines. In “Grain Belt Blues, Pt. One” Mr Leoni appears as a well-wrought and anatomically accurate lion, rendered in intricate detail. The characters in the later stories are striking because they are rarely abstracted into iconic signifiers; no matter how humanly the characters interact, their representation refuses to settle the question of their nature by depicting them in caricature. The “animalness” of the characters’ look is contradicted by their all-too-human activities, and this ontological friction has a corollary in the nihilism bubbling underneath the stories, as the characters contemplate the existence of God and moot the purpose of their own lives. The characters question what they are or meant to be, and so too does the reader.

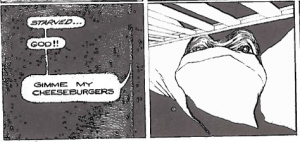

With the exception of “Mound City,” a two-page comic about Sleaze the Salamander’s inauspicious attempt at pitching for an amateur baseball team, the other stories are much longer and the locations shift rapidly as the male protagonists search for female companionship and the next party. These comics have affinities with that classic novel of itinerant life, Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (1957), but just as the hedonism of Kerouac’s narrative is interspersed with the dull necessity of earning enough money to eat, careering across the Midwest in Prairie State Blues is an unglamorous and frustrating activity: Sleaze is sacked because his colleague was drinking on the job, the girl he is searching for is never found, his car runs out of petrol. Sleaze would do well to acclimatize himself to disappointment: at the start of “Tristate Blues” he tells his housemate Donny not to eat the cheeseburgers in the fridge, and after a twelve-page odyssey Sleaze returns home to find… well, we only see this scene from a fridge-eye’s-view, but Sleaze’s facial expression speaks for itself (see fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Panels from “Tristate Blues,” Prairie State Blues. © Bill Bergeron 1971.

The Prairie State is dangerous as well as disappointing: “Grain Belt Blues, Pt. One” is a manic chase after a runaway train, culminating in an rail accident. The fate of Sleaze is unclear; he could have been killed, although the positioning of this comic near the start of the collection, with Sleaze reappearing several times afterwards, may indicate his survival.

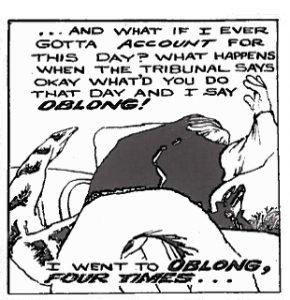

In these funny animal comics the attempt to attain the object of one’s desire never succeeds, life is violent and disordered, and religion (primarily Catholicism) is a source of ridicule. In the final panel of “Mound City,” with Sleaze’s unsuccessful stint as pitcher concluded, his replacement reaches down and asks whether someone has lost a cross on a chain. Even a humorous strip like this implies that Sleaze has lost his faith. Certainly his Catholicism has slid into a radical ontological despair in “Tristate Blues” when, discovering that he is continually crossing through the nondescript Illinois town of Oblong, Sleaze starts shouting at his inanimate surroundings, beginning by saying “I don’t believe it! […] There is no Oblong, Illinois – or any place else, for that matter!” and becoming angrier and angrier (see fig. 4):

Fig. 4. Panels from “Tristate Blues,” Prairie State Blues. © Bill Bergeron 1971.

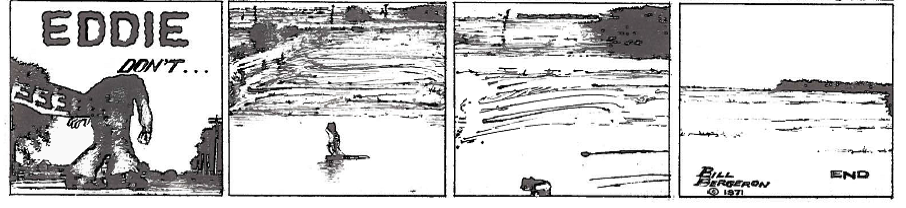

Sleaze retains a Christian framework for understanding the world, which in some ways is his problem: he wants his nonstop skidding across Illinois’s plains to mean something, to lead somewhere, to be of consequence in the final judgement of his time on Earth. Unfortunately his journeying leads him back to where he started and an empty refrigerator, or he is involved in a train accident, or, as in “Sag Channel Blues,” his travels end with abandonment by the side of the road (see fig. 5).

Fig. 5. Panels from “Sag Channel Blues,” Prairie State Blues. © Bill Bergeron 1971.

Bergeron’s composition of the final row of panels is worth our attention: Sleaze becomes a much smaller figure in the second panel, and is only half visible at the bottom of the third panel, crouching or walking off. The fields in the background are a recognizable mess of horizontal lines in the second panel, but those lines become more frenetic in the third: the landscape in the middle distance is depicted by lines of such inconsistent thickness – and seeming haste in production – that Sleaze appears to be vanishing out of a work of abstract expressionism. In the last panel there are fewer lines and the ink has been more carefully applied. There is scarcely more detail in that final panel, but the horizon line is unambiguous, and the modest use of lines indicating undergrowth produces the effect of a still landscape. There is nothing to signify the noise of the Midwestern countryside. Once Sleaze exits the narrative the surroundings are no longer shown as he sees them, the land no longer belittles his fixation on meaning and presence with its random swirls. In the final panel the Illinois prairies producing Sleaze’s melancholy (an environment which stimulates him to rage in “Tristate Blues”) are nondescript and unobtrusive. Perhaps they are indeed blank of meaning, but Sleaze projects onto them a chaos that confirms his fear of worthlessness and insignificance.

“Grain Belt Blues, Pt. One” begins with an epigraph from Herman Melville’s Moby Dick (1851), “Nantucket is no Illinois” (55), a statement functioning in Melville’s novel to differentiate the isolated island of Nantucket from the land-locked Prairie State. This quotation operates differently in Bergeron’s book, ironically inviting the reader to see that Melville’s world of whaling on the high seas is not so unlike life in the Midwest. In Bergeron’s telling the Illinois wildlife is also potentially lethal and the sphere of labour is arduous, always on the move and overwhelmingly male. Existential themes dominate Moby Dick (‘transcendental themes’ might be the better term) and Prairie States Blues, and in the former book Captain Ahab thirsts to drive a harpoon into the eponymous whale:

All visible objects, man, are but as pasteboard masks. But in each event […] some unknown but still reasoning thing puts forth the mouldings of its features from behind the unreasoning mask. If man will strike, strike through the mask! How can the prisoner reach outside except by thrusting through the wall? To me, the white whale is the wall, shoved near to me. Sometimes I think there’s naught beyond. But ‘tis enough. […] That inscrutable thing is chiefly what I hate (145; italics not in original).

Ahab wonders if “visible objects” like Moby Dick are “masks” concealing “some unknown but still reasoning thing” underneath – or is there “naught beyond”? Is the surface of things all there is, or does a deeper truth exist behind this world of masks? Ahab’s answer is to “strike through the mask” and on one level it does not matter what he discovers, since it is the not knowing, the difficulty of reading the whale, its inscrutability that Ahab wishes to eradicate. Although Melville resists pinning down the meaning of Moby Dick’s inscrutable colour, in a later chapter the novel asks of “this whiteness”: “Is it that by its indefiniteness it shadows forth the heartless voids and immensities of the universe, and thus stabs us from behind with the thought of annihilation” (175)?

Bergeron’s one-page comic “Sometimes” contemplates a similar question as the timber wolf narrator stares up at a blank ceiling. The wolf lies next to another wolf in a dishevelled bed, voicing its fears: “Sometimes, and it’s never when I’m alone I look at the angle of the ceiling and the wall and I see the nothingness, what Goya called the Nada, – beyond – and I’m very much afraid.” It is a sombre piece and undoubtedly the wolf’s fears are those of many other characters in the collection.

Fig. 6. Panel from “Sometimes,” Prairie State Blues. © Bill Bergeron 1971.

Provocatively, the panel in which the wolf looks most human, lying with hands behind head (see fig. 6), suggests the reclining confidence of a male who has just had sex. That the wolf only ever sees the nothingness when he has a sleeping companion is easily missed but utterly significant: with each sexual conquest the wolf contemplates the nothingness of the universe, and the satisfaction implied by his post-coital position is contradicted by the ennui that follows in its footsteps. This seems like a riposte to characters like Sleaze and Bent-Down Bunny (and the sexual adventurers of the underground comix more generally) who we see hotly pursuing women to sleep with: even if they are successful, they will not feel their lives are any less alone or any less futile. Prairie State Blues invites us to see their search for females, their macho braggadocio, their misogyny as desperate acts of constructing a masculine self that will shore against the anxiety that they are living meaningless lives in a harsh world without redeeming purpose. The wolf intuits this, at least to the point that sexual conquests do not aggrandize his identity but remind him how vacant his life is.

The last three comics in Prairie State Blues are short and enigmatic. The conjunction of heterosexual male pride and fear of death or nothingness returns in the third-from-last story, “I recently lay abed,” in which the reciter is a pompous hypochondriac who has diagnosed himself with tuberculosis; the monstration includes exteriors of buildings and indistinct humans. This first-person reciter could conceivably be the ex-Illinoisan discussed above, but the elaborate vocabulary suggests someone we have not yet met. The reciter’s girlfriend disagrees with his diagnosis and in protest he starts to plan his funeral: “My girlfriend would not be invited.” He mentally choreographs the rites so the mourners appear “dramatically mysterious,” and the narrator begins to count the female attendees but is too tired to complete the exercise. At this moment of sickness, of emasculation, where his knowledge of his self is dismissed by his girlfriend, the male imagines a funeral where his masculinity is demonstrated by the volume of females: “the number of women in attendance would be important; especially the number crying.” The narrator is barely credible as a character, but “I recently lay abed” picks up the gendering of existential angst in “Sometimes”: the assertion of manhood in the face of death is turned into a childish act that underlines the narrator’s impotence and invites us to laugh aloud at him. Bergeron is not glamorizing ennui but ironizing it.

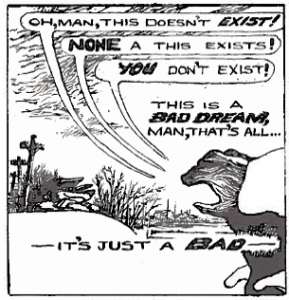

The penultimate story “In the beginning” twins the opening lines of the Book of Genesis with a shark swimming underwater, drawn with great attention to anatomical accuracy and with no visual concession to anthropomorphism. The relationship between recitative and monstration is murky, especially when the comic ends in panel six with the shark swimming out of the field of vision (see fig. 7).

Fig. 7. Panel from “In the beginning,” Prairie State Blues. © Bill Bergeron 1971.

For an understated comic this last panel has been constructed for maximum dramatic effect, changing the order of words as they appear in Genesis: “And God saw that it was good” should appear between panels three and four, not in panel six. What is the meaning of the juxtaposition of image and quotation in this last panel? It could be dismissing the idea of an orderly world, created by God, where Man has kingdom over the animals. The deep black ink of the last panel conjures up an arbitrary universe devoid of meaning, with the shark conveying a brutal battle for survival. Here the monstration mocks the recitative and the notion of a God satisfied with Creation. We swim out of the void, we end our days staring into the void, and the time in between must be spent dodging ruthless predators whose only moral standard is the search for their next meal.

This panel, of course, is not necessarily a rejection of God’s Creation, but an acknowledgement that animalkind has been deliberately wrought – although the reasoning behind Creation may be beyond humanity’s ken. There is something of William Blake’s poem “The Tiger” (1793) in this panel. Faced with the shark but reading that God saw his Creation “was good,” one might well encounter this last panel and muse “Did he smile his work to see? Did he who made the Lamb make thee?” (122). “In the beginning” moots but does not answer those questions and refuses to align the texts in Prairie State Blues in a coherent row. The previous stories of ennui and angst are not answered by epiphany, but neither does “In the beginning” confirm the characters’ recurrent nihilism. “In the beginning” frustrates because it refuses to pass a final statement on what we have seen in the book, deferring that possibility to the very last text in the collection, “Rocks in my bed.”

It is ironic that this last text does not use the word ‘blues’ in its title, since this comic is closer to the blues than any other text in the collection: the recitative is a reproduction of song lyrics written by Leroy Carr and Robert Johnson and the monstration is a series of images of the landscape, buildings and people. The lyrics declare that the reciter can “sleep good no more,” reiterating the insomniac anxiety of “Sometimes,” but in “Rocks in my bed” the sleeplessness derives from the pressing and concrete presence of violence nearby. The reciter needs his guns, perhaps to defend against the “[b]lacksnakes crawling all ‘round my door,” presumably a reference to encroaching reptiles and to companions who prove treacherous and wish one ill.[vi] The landscape in the monstration, as it is throughout Prairie State Blues, is finely wrought by Bergeron’s pen, but there is little time to enjoy the view in this hostile environment. The reciter has to “leave here running because walkin’ is much too slow,” a mood of movement common to black Atlantic musical traditions (Gilroy 111). Prairie State Blues wrests the lyrics into a Midwestern setting, where itinerancy does not provide any succour to the existential questioning of Sleaze, Bent-Down Bunny and the timber wolf, although moving on might be a practical step (staying still is dangerous on these prairies, with people you can’t trust posing as your friends).

All the comics in Prairie State Blues use the same grid pattern, twelve panels to a page, four wide and three high, but the pages are not always filled up. In their study of Eddie Campbell’s autobiographical comics, Craig Fischer and Charles Hatfield identify the same disinclination to fill the comics page, ending the “comic book text […] at mid-page, without some final panel or panels, or other graphic device, to fill the vacant space beneath.” This is “quite unusual” in comics and Fischer and Hatfield read “the blankness beneath [as] a form of punctuation or token of finality” (85). These areas of unprinted paper, betokening “finality,” pop up throughout Prairie State Blues, and the three comics at the end all leave half a page or more of blankness after the final panel. Because “Rocks in my bed” is fourteen panels long it only just exceeds one side of paper, and its last two panels leave the book’s closing page largely empty. Does this signify the void in which the characters are languishing? Is this a symbol of the end of their voyaging? How this space relates to the other stories is up to the reader to interpret and there is no easy connection between this final comic and the previous ones in the book. I argued that, in the texts featured earlier in Prairie State Blues, the restlessness of the funny animal characters was interwoven with their anxious construction of a masculine self. For me, “Rocks in my bed” provides no resolution to this, only the ambiguous suggestion they will be on the move for a while longer yet.

August 2014

Endnotes

[i] On the Chicago Review Press website their early publications appear to be guidebooks, novels and poetry in translation.

[ii] Prairie State Blues was also reviewed in Barrier 36-40.

[iii] Dunn and Morris cite the SF critic Eric Rabkin as their inspiration for the term. This usage shifts away from the early-twentieth-century meaning of ‘composite novel’: a novel produced by collaboration between authors, each working on a different part (Dunn and Morris 2).

[iv] I have tried, gently, to incorporate the terminology of Thierry Groensteen and his theory of comics narration into this essay. For Groensteen it is convenient to identify “the ultimate instance responsible for the selection and organization” of material going into a narrative comic as the narrator. This narrator delegates its responsibilities to a monstrator, the generator of drawn elements, and to a reciter, “responsible for [the] narration” in the accompanying words. Accordingly Groensteen calls the visual enunciation of a comic the monstration and the verbal enunciation the recitative (84-95).

[v] An issue that looms large in philosophy more generally. Musing on humankind’s inability to conceive of its own extinction, the critical theorist Jean-François Lyotard contends “it’s impossible to think an end, pure and simple, of anything at all, since the end’s a limit and to think it you have to be on both sides of that limit” (129).

[vi] The ever-presence of the serpent would support a reading of the world in this collection as not meaningless but fallen.

Bibliography

Barnes, Julian. A History of the World in 10 ½ Chapters. 1989. London: Picador, 1990. Print.

Barrier, Mike. “Funny Books.” Funnyworld 16 (Winter 1974-75): 36-40. Print.

Blake, William. Selected Poetry. Ed. Michael Mason. Oxford: Oxford UP, 1996. Print.

Dos Passos, John. U.S.A. 1930-36. London: Penguin, 2001. Print.

Dunn, Maggie, and Ann Morris. The Composite Novel: The Short Story Cycle in Transition. New York: Twayne, 1995. Print.

Fischer, Craig, and Charles Hatfield. “Teeth, Sticks, and Bricks: Calligraphy, Graphic Focalization, and Narrative Braiding in Eddie Campbell’s Alec.” SubStance: A Review of Theory and Literary Criticism 40.1 (2011): 70-93. Print.

Geerdes, Clay. Comix World 3 (Dec. 1973). Print.

Gilroy, Paul. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. London: Verso, 1996. Print.

Groensteen, Thierry. Comics and Narration. Trans. Ann Miller. Jackson, MS: UP of Mississippi, 2013. Print.

Ingram, Forrest L. Representative Short Story Cycles of the Twentieth Century: Studies in a Literary Genre. The Hague: Mouton, 1971. Print.

Kennedy, Jay. The Official Underground and Newave Comix Price Guide. Cambridge, MA: Boatner Norton Press, 1982. Print.

Kennedy, J. Gerald. “From Anderson’s Winesburg to Carver’s Cathedral: The Short Story Sequence and the Semblance of Community.” Kennedy, Modern 194-215.

—. “Introduction: The American Short Story Sequence – Definitions and Implications.” Kennedy, Modern vii-xv.

—, ed. Modern American Short Story Sequences: Composite Fictions and Fictive Communities. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1995. Print.

Kerouac, Jack. On the Road. 1957. London: Penguin, 1972. Print.

Lyotard, Jean-François. “Can Thought Go On Without a Body?” Trans. Bruce Boone and Lee Hildreth. 1987. Rpt. in Posthumanism. Ed. Neil Badmington. Basingstoke: Palgrave, 2000. 129-140. Print.

Melville, Herman. Moby Dick. 1851. Ed. Tony Tanner. Oxford: Oxford UP, 2008. Print.

Witek, Joseph. Comics Books as History. Jackson, MS: UP of Mississippi, 1989. Print.