F.W. Murnau’s 1922 film Nosferatu is undoubtedly one of the most iconic films of the German Expressionist movement. Expressionist techniques which create an unnerving atmosphere can be seen throughout the whole film, but this blog post will mostly focus on the scene in which Count Orlok climbs the stairs and enters Ellen’s bedroom to drink her blood.

The shot of Orlok ascending the stairs after being invited in to Ellen’s room perfectly encapsulates Expressionist imagery, and may even be the most famous shot of any Expressionist film. German Expressionism has been referred to as “the world of light and shadow” by Ian Roberts and this shot helps us understand why that is. We only see Count Orlok’s shadow rather than Orlok himself, which makes the figure stand out more and accentuates features such as his long, claw-like fingers which makes him look more threatening.

We then see Ellen spin round dramatically as she senses Orlok entering the room. In contrast to many films of this era which used more restrained acting, Expressionism often uses large, bold movements, exemplified here. While the bedroom in this scene is relatively bare, expressive mise-en-scene is used to great effect in Expressionist films, perhaps more notably in The Cabinet Of Dr. Caligari (as seen further down) where the set design is extreme and distorted, in contrast to the slightly more realistic albeit still unnatural and disconcerting mise-en-scene of Nosferatu.

As Orlok opens the door, we again see that his fingers and nose have been exaggerated, and how inhuman he looks. Jagged, sharp shapes are a feature of Expressionism, as seen here in a shot from The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari. This shot also shows the use of shadows in Expressionism. Interestingly, many of the shadows in Dr. Caligari were not real shadows but were instead painted directly onto the floor of the set, which shows how important light and shadow were to Expressionist filmmakers.

As Orlok enters her bedroom, Ellen clutches at her heart in horror as she sinks onto the bed. There is a look of abject terror on her face, which is not uncommon in Expressionist films as they often have fantasy and horror elements as well as the expression of extreme emotion. Themes of seduction are also present in Nosferatu, and it can be argued that both Ellen and Count Orlok aim to seduce each other, Orlok so he can drink her blood and Ellen so she can defeat him.

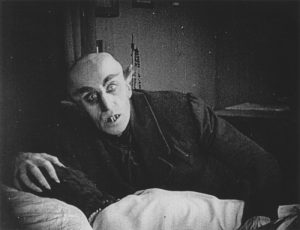

As Count Orlok looks up, we finally see him in a close up, and so can see the ways that Murnau made him look as terrifying as possible. His teeth and ears are much larger than normal and he has a wide-eyed expression on his face, amplifying his fear. The cuts between various locations in this scene are much slower than in other movements such as Soviet Montage, as Expressionist filmmakers mostly used a slower camera which they moved around in inventive ways rather than frequent, quick cuts.

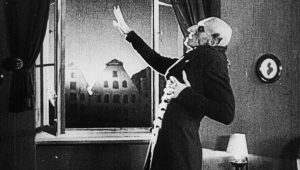

One of the final shots of the film is of Orlok realising that he stayed too long and the sun has now come up, and he grabs at his chest as he disappears. This ending is bittersweet as while the evil has been defeated, it came at a great cost. Parallels can be drawn between this ending and early Russian films such as Twilight of a Woman’s Soul, which usually had sad endings, although Nosferatu’s ending is not quite as negative.

Both Nosferatu and Dr. Caligari, along with other Expressionist films like Metropolis, have a much more complex narrative than other films at the time. They feature a story with characters who we follow, whereas for example Soviet Montage films often do not focus on any one character but instead follow a crowd. This climactic sequence from Nosferatu is useful to look at as we can see how Murnau uses Expressionist techniques to not only give his film a distinctive aesthetic, but also to change the way the film affects us.

TUTOR FEEDBACK:

The post is generally well written, and the group make some good use of focusing quotations to aid the analysis and pick out a range of good details. For this kind of task, it would have helped to set up the analysis by beginning with a clearer definition of what German Expressionism is, outlining some of its key traits: the opening statement that it focused on creating an ‘unnerving atmosphere’ isn’t comprehensive enough to guide the analysis as a whole. As the piece progresses, however, the group better evidence their understanding of Expressionist techniques in the focus on performance style and set design, and the cross-references to Caligari help flesh out the discussion. Structurally, the writing jumps around a little between ideas (in the same paragraph the group stiches together a comment about facial expression with a reference to the pace of editing and a contrast to montage – this doesn’t clearly link to the line of argument that precedes it). Proofing and briefly editing the post before it goes live can help smooth over these kinds of things.