An intimate reflection of a movement awash with connotations of revitalization, ‘new youth’, vitality and sexual openness, draws our attention to the pitfalls (or arguably, lack thereof) of its being; specifically concerning the presentation of women. Whether marginalised, or apotheosised, the crux of our argument lies within the shift of the image of the woman; observing differences via a male centered perspective and equally contrasted with a female centered perspective. For the purposes of this discussion, we shall interrogate the female body, the position of the female within French New Wave films, underpinned by referencing Cléo de 5 à 7 and Vivre Sa Vie, as well as discussing Varda’s unique position within French filmmaking; predominantly through her focus in editing and representing the

female entity.

Despite the French New Wave, or ‘La Nouvelle Vague’, being considered “one of the most significant film movements in the history of the cinema.” (Neupert xv) and the Lumière brothers being credited as some of the pioneering founders of cinema, “French domination of world production was short lived, for the French had thoroughly underestimated the competition from America.” (Kline 3). The movement itself, separate from French national cinema, only “existed for a limited period of time […] whose emergence was favoured by a series of […] factors intervening at the close of the 1950s” (Marie 2). Whilst being influential in the creation of cinema, France never possessed true monopoly and failed to capitalise regardless of their early advantage, and were consequently overwhelmed by hegemonic forces such as Hollywood. The recent conclusion of World War II and beginnings of a sexual revolution were potentially some of the various factors that impacted the French New Wave, as humanity progressed into a more liberal, experimental and free society; expressed and documented in art forms – particularly film. Influence of stylistic features can also be identified from previous film movements, such as Italian neo-realism. Directors like Varda’s early work demonstrates particular qualities, for example, her first feature “was shot on location, with local, non-professional people playing all but two roles” (Neupert, 58); paralleling the illustrious techniques of Italian neo-realists.

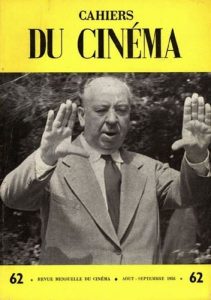

According to Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell, ‘the principle Nouvelle Vague directors had been film critics for the magazine Cahiers du Cinema’ (443), of which the ‘five core’ directors [were;] Claude Chabrol, Francois Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Eric Rohmer and Jacques Rivette’ (Powrie and Reader 20). Despite contributing to the New Wave Movement, these directors rejected their predecessors Post-War (1945-1959), and were ‘stigmatized [by Truffaut as] the cinema de papa (‘Daddy’s Cinema’)’ (Powrie and Reader 16). The rejection of these French father figures of film, such as ‘Claude Autant-Lara’ or ‘Jacques Becker’ (Powrie and Reader 16), was replaced by favouring the portrayal of the rising youth culture.

For the main male directors of the ‘New Wave’ movement, this theme was narratively and stylistically presented, whilst adhering to the ‘auteur policy’, which believed that ‘the director should express a personal vision of the world’ (Thompson and Bordwell 443). The result of this is that ‘the majority of New Wave films […have…] a male protagonist whose point of view is the dominant perspective of the film which he features,’ (Sellier 126) and even in the ‘limited number of (male authored) New Wave films that took a female subject as their […]protagonist, […] the dominant viewpoint still comes across, implicitly or explicitly, as that of a male character…’ (Sellier 128). Although, having seemingly rejected the previous generation of patriarchal ‘Daddy’s Cinema’, the male ideologies of the position of women in society are still present within the New Wave movement, encouraged by their filmmaking practices; generating a domination of the male point of view.

As aforementioned, “challenging the American model of commercial cinema, the New Wave encouraged directors to see themselves as part of a worldwide confraternity of kindred spirits” (Greene 2). As Cahiers du Cinema was comprised predominantly of males, preceding ‘Daddy’s Cinema’, women’s contribution to film was marginalised, therefore it was essential for the triumphant few to represent femininity in the way that they saw true. Varda’s work remains to be reflective of her own personal motivations, it becomes very encouraging especially when concerning issues of male dominance in industries of power, such as the media and government. In the years just prior to the arrival of the New Wave, women had only just been granted permission to stand in authoritative positions, such as being members in the House of Lords in Britain from 1957.

Being one of the first women to reject the mainstream group of core directors and become a member of the ‘Left Bank’ group, Varda’s position as a female director was revolutionary. Thompson and Bordwell note that the Left Bank Group were, “[m]ostly older and less movie-mad than the Cahiers crew, they tended to see cinema as akin to the other arts, particularly literature” (17). Varda was involved in a complex and intimate relationship with the female identity and portraying women from a female perspective. Alison Smith explores this as “she deals with Varda’s desire to establish a relationship between her films and the people she made them about (or for)” (Gasster-Carrièrre 363).

The directorial influence of Varda existed not only from behind the camera, but through the manipulation of actors and actresses in front of the camera. Varda herself was apotheosised and celebrated because she attempted to prevent the marginalisation of females in cinema and the film industry, with her “importance…eventually felt beyond France’s borders, encouraging other young women to pick up the camera and begin making personal films” (Neupert 56). Varda’s representation of women, especially in Cléo de 5 à 7, can be compared and contrasted to the approach male New Wave directors, like Godard, adopted. Vivre sa Vie, like Cléo de 5 à 7, has a female protagonist, however in Godard’s film, the character is a prostitute. Nana’s life is centred on her sexuality, as her body supports her livelihood by providing pleasure to men. Both Nana’s life, and ultimately her death, are under the control of the opposite sex, thus marginalising Nana, suggesting that she is dependent and incapable of living without a male counterpart. Conversely, it is women who orchestrate the narrative in Cléo de 5 à 7, beginning with a female fortune teller, each decision that follows is made by Cléo, expressing herself when faced with detrimental health problems.

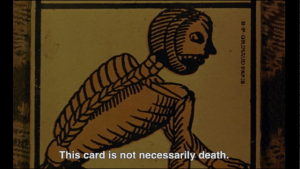

Furthering the ideas of representation of women in the ‘New Wave’ movement, the female form is a battleground of ownership in terms of who uses the anatomy within film and for what thematic or ideological purpose. The appearance of the sexualized female form, which resonates with the prominent characteristic of sexual openness within the ‘New Wave’, is challenged by Varda in Cléo de 5 à 7. The association of the female as a catalyst for life, is instead replaced with death in the first scene of the film where Cléo has her tarot cards read, as the extreme close up of the last card ‘Death’ confirms.

The replacement of life for death (such as the conception of cancer) is not only narratively evident as, ‘both preoccupations have a similar bodily location’ (Smith 98); but is later visually emphasized when Cléo watches the street showman. During their performance, they physically show with their own bodies, flesh being invaded by ‘alien, vaguely sinister objects and pain’ (Smith 98), in the form of hooks and swallowing frogs. This highlights the ‘body’s fragility’ (Smith 98), and how the possibility of cancer has changed the beautiful outward appearance of the female form, to a carrier of death. Varda also uses Cléo’s body and impending cancer confirmation to incorporate political ‘references to the Algerian War into [her] work without falling foul of the censor’ (Powrie and Reader 26). Powrie and Reader note that when Cléo and Antoine the soldier meet, it is a ‘counter posing of a life under threat from within and one under threat from without’ (26). The internal conflict in Cléo, also embodies the ‘French national identity’ (Betz 140), in the context of the Algerian war, which the presence of the soldier heightens. Throughout the film, Varda uses the symbolism of female form to combat not only male ideologies of the societal role of women, but also to incorporate political information, that would otherwise be left untold.

Sandy Flitterman-Lewis (1996) provides a compelling argument concerning Varda’s portrayal of Cléo’s feminine identity; interrogating the structure of the film as a way that dictates Cléo’s female position within the film. It can be argued that there is a distinctive way in which Varda portrays Cléo, and this can be analysed by separating the film into two halves, in which her identity changes dramatically, and perhaps comments on Varda’s own values and the way that the female form adheres to certain aesthetics in film. Foremost, the first half of the film makes reference to Cléo’s dependence on her self-image; noting her existence through the eyes of others and viewing herself as the“object to be looked at” (Smith 100).Varda makes explicit use of mirrors as a way of looking, with Cléo using them as a way to disassociate herself with her own existence; allowing herself to be absorbed into the surrounding world.

Further, Laura Mulvey’s theorisation of the “woman as image, man as bearer of the look” (837) is ever more important throughout the film, as although Cléo is not coded for “erotic impact” (Mulvey 837), she has been associated with the connotations of “to-be-looked-at-ness” (Mulvey 837); arguably marginalising her. Perhaps this suggests Varda’s lack of respect for the female body, as her reliance on mirrors exposes the insecurity of the female being, and reduces her to an object.

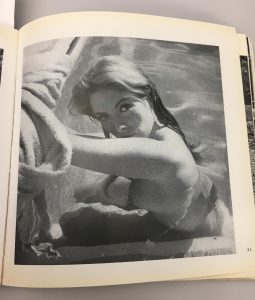

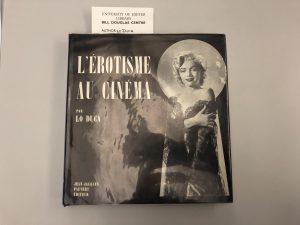

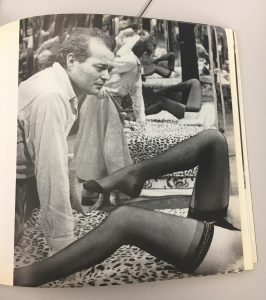

This continued notion of the female form as an object constructed for “erotic impact” (Mulvey 837) draws parallels with L’Erotisme Au Cinema (Lo Duca); a collection of images exploring female eroticism within cinema. The artifact finds its relevance not only concerning our argument, but within Film History as it comments on the exploitation of the female figure in front of the camera. Lo Duca compiles an intimate reflection on the female form of popular stars; our main focus being Brigitte Bardot – as she is instated as a key figure within French cinema. Although L’Erotisme Au Cinema illustrates raw, uncensored women within French cinema, our argument is that being vulnerable isn’t always about being naked or explicitly depicted, as shown within the catalogue of photographs, but female vulnerability takes a form in many facets; such as loss of self and disassociation from the outer world, mirrored in Cléo de 5 à 7. However, a point of similarity is that both the artifact and the films depict women as being the object of desire; thus, perhaps suggesting that across varying artistic mediums, the female is always marginalised at the core.

Alison Smith notes that Varda was a woman that “based her whole life on a status as a woman seeing” (100), taking active roles within the American feminist movement in 1967; therefore, perhaps a counter of this argument would see that Varda’s marginalization of the female form is a springboard into deeper interrogation of the female identity, as she projects an idealised identity on to Cléo. By deconstructing Cléo’s identity and transforming it into a figure that isn’t solely reliant on superficialities; but is rebuilt into something greater than her prior vacuous existence; comments on Varda’s true intentions of celebrating the female identity, whilst revealing the complexities of female stars. Comparatively, the second half sees Cléo elevated from her prior identity. It could be argued that Varda’s argument is now focused on the empowerment of Cléo, as the fear of death makes her want to live, commenting on her shifted perspective of the world as she is transformed into a figure that overcomes strife wrought by the possibility of illness and a loss of identity. By uncovering the personal strife of a woman, you begin to understand her at her most vulnerable, however, Varda subverts this vulnerability in the latter part of the film. As Cléo transitions from rehearsal to her final performance, there is an obvious shift in her identity. In rehearsal, she is less aware of the audience, adopting a passive role that becomes the object of desire; letting her friends surround her. Whereas, in comparison, her performance isolates Cléo against a dark background as she becomes more aware of her audience; regaining an active, empowered role. It could be appropriate to argue that Varda is giving her back her voice, viewing her as a multidimensional character not only concerned with appearance, but as a spectacle.

Concluding our research into the marginalisation, or apotheosised presentation of women, our evidence suggests that both statuses are applicable within the time period of the French New Wave and the historiographies of writers presenting their own historiographical deductions. Not only concerning the roles women were given as auteurs and actresses, but the conflicting symbolisms that the female form is used to communicate and the contrasting status of object or subject. Doing ‘film history’ by questioning the type or lack thereof of the recording of women and their portrayal, has revealed that the womens voice or indeed point of view within the New Wave, isn’t as prevalent or as canonized as the males. This mirrors how Jonathan Rosenbaum writes that there was a ‘sense of male privilege underlying much of the French New Wave’ (www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2009/04/sexism-in-the-french-new-wave/), which is evident in the gender of canonized directors, the narrative that supports male ideologies of the social role of women, and the frequent sexualisation of the female form.

Works Cited:

Genevieve Sellier, ‘Gender, Modernism and Mass Culture in the New Wave’ in Gender and French Cinema, (eds.) Alex Hughes and James Williams, (Oxford: Berg, 2001) pp. 126-128

Greene, Naomi. “The French New Wave: A New Look“, Defining Traits of the New Wave, (London: Wallflower Press, 2007).

Kline, T. Jefferson. “Unravelling French Cinema from L’Atalante to Caché”, (Oxford: Blackwell, 2010)

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema”, Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings. Eds. Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen. New York: Oxford UP, 1999, pp. 837. Print.

Marie, Michel. translated by Richard Neupert, “The French New Wave, An Artistic School”, (Oxford: Blackwell, 2003).

Neupert, Richard. “A History of the French New Wave Cinema” (Wisconsin, University of Wisconsin Press, 2007).

Peary, Gerald. “Agnès Varda.” Agnès Varda: Interviews, edited by T. Jefferson Kline, Mississippi UP, 2014, pp. 89–91. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt2tvpbv.15.

Powrie, Phil and Keith Reader. “History.” French Cinema: A Student’s Guide, (London: Hodder Education, 2008) pp. 16-26

Rosenbaum, Jonathan. Sexism in the French New Wave, April 10th, 2009. www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/2009/04/sexism-in-the-french-new-wave

Smith, Alison. “Agnès Varda”, French Film Directors. Manchester UP, 1998, pp. 96-102. Print.

Thompson, Kristen and David Bordwell. “Film History: An Introduction“, 2nd Edition (London: McGraw-Hill, 2003), pp. 443

Word Count (excluding ‘Works Cited’ and captions): 2166