What are the problems and challenges that early cinema poses for you as film historians?

In order to understand the true intention of the films created during the early cinema period it is important to consider the wider range of context, not only within the narrative plot of the film itself but also the audience and society it is being exhibited to. It can be difficult to understand the way in which society in the early 1900s worked as it contrasts so heavily with our modern world, and to combat this we found it was essential to remember the “Cinema of Attractions” principle and the innovative technology that cinema presented for the time. Society at the time was mainly composed of poorer classes, meaning that those viewing the films were from middle-upper class backgrounds, which is an important element to note as it means the target audience for the filmmakers needs to be more targeted towards the bourgeois.

It is also difficult to come to a definitive answer as to what Film History/early cinema actually is and when it originated. This is partly due to the progression of each nation in the film industry expanding and developing at different rates and all contributed different forms, and also the lack of films recovered from the period for us to analyse today. Deutsche Kinemathek claims that 80-90% of silent films produced during the late 1800s- early 1900s have been lost, creating a huge void in the content produced as a collective and to some extent formulating a narrow view for us as historians to try and understand. By only being able to study a small selection of the potential texts of the time it is challenging to form an accurate depiction of what the film industry and society were actually like.

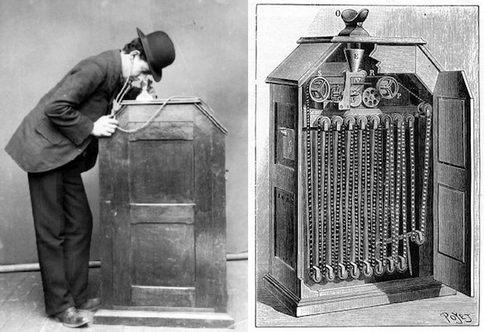

However despite the lack of actual films from the period it is important to acknowledge that film history cannot be studied only from the films themselves, but also through the prints, articles and apparatus of the time. Understanding the films produced at the time relies on the understanding of their context (e.g. the camera they used and how that affected the style of films). Therefore, the challenge in studying film history is the vast amount of sources that are needed to be studied in order to fully understand the developing styles in early cinema and their purpose.

What has surprised you about the material you have seen thus far, from the 1890s- 1910s?

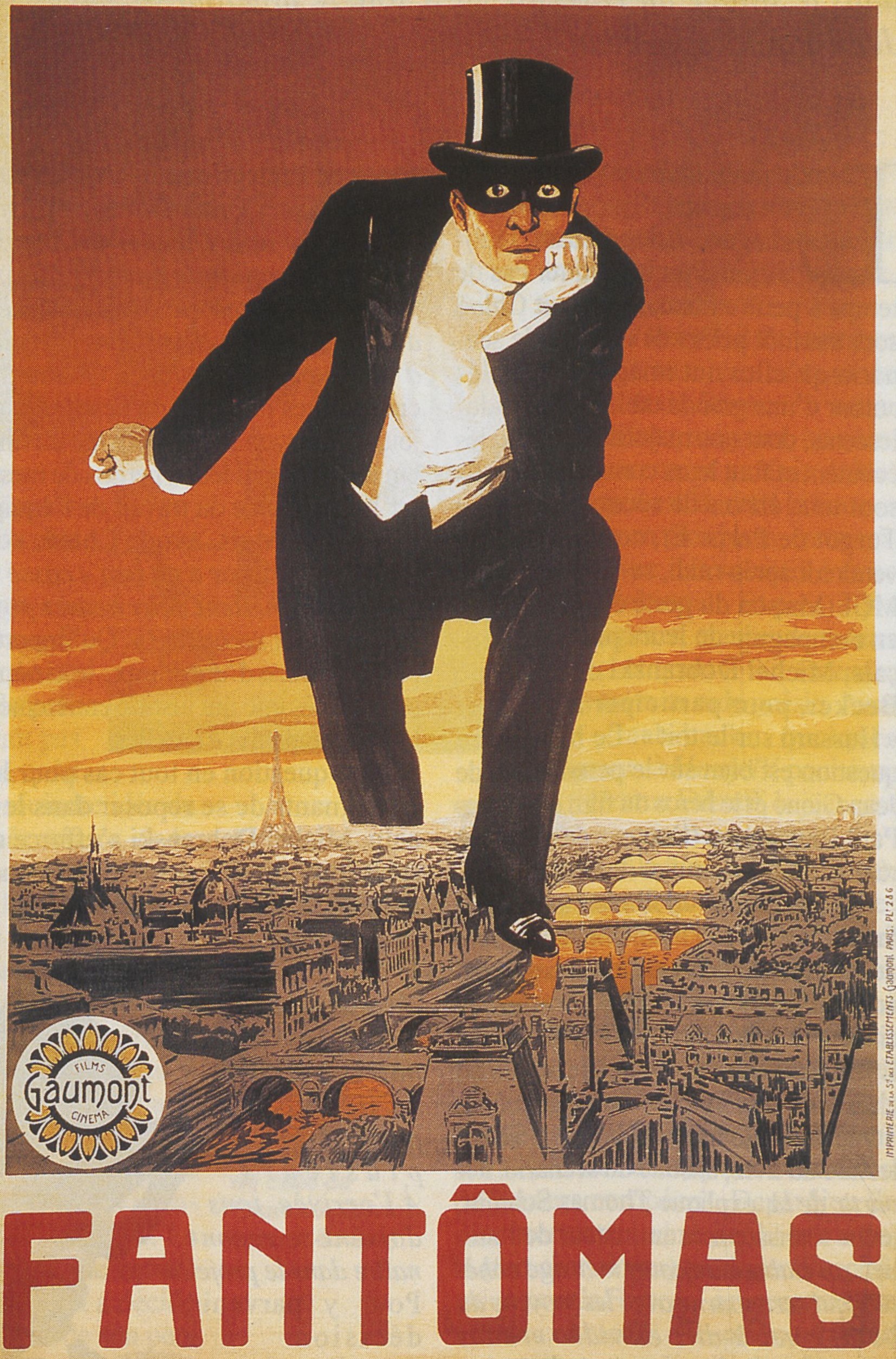

One of the most noticeable things that surprised us was how quickly the films developed from silent shorts with shallower narratives to longer films that incorporated sound and a more complex plot, with some such as Fantomas (1913, Louis Feuillade) expanding into serial narrative styles. These later films became a lot more entertaining to us as, unlike the society of the early 1900s, we couldn’t revel in the same novelty of cinema as a form of entertainment. As a result more intricate plots and experimental cinematography capture our attention and intrigued us. It was also interesting for us to witness the origins of our modern day practices in the early films and experience directly how they came to fruition and understand why they are still used today.

It was also surprising to see the way in which films differed between countries in terms of style and story telling techniques. For example, the early American films seemed to value cinematography and style above other aspects of filmmaking. This can be seen in Suspense (1913, Lois Weber), in which many of the shots are disorientating and non-stationary. The aerial shot of the beggar by the door was a great example of how experimentalist cinematographers were becoming; positioning the camera to show us the perspective of the wife looking out at the window help us engage and experience the exact same events as she did.

On the other hand, many French films at the time seemed to value story-telling over style. For example, Fantamas (1913, Louis Feuillade) relies on the gripping story, while maintaining the stationary camera, and leaves the audience on a cliff-hanger and eager to return to the cinema to watch the next instalment.

What particular skills might we need to employ in order to get the most out of studying this kind of cinema?

As students it is important for us to maintain a logical and analytical method of critique when viewing and studying material from early cinema, focussing on a holistic approach that broadens our understanding further. Not only do we need to understand the audience, society and constant of the films, we also need to recognise the technology and equipment used to produce and exhibit them. Using film to shoot requires a different process of development and editing than the digital filming of our modern day cinema, and by acknowledging this we can see how this affected production and overall working environment of the early cinematic industry.

It is also important to understand the early films from the perspective of the audience at the time. By doing this we are able to study to context of the films, as well as their meaning and purpose, giving us a deeper insight into why and who they were made.

This is a highly comprehensive and detailed post that charts your experiences with film history thus far. For the most part, it is highly impressive work that shows real insight and research, as well as thoughtful use of images and gifs.

One point from the outset, however, is that it is too long! I’m delighted that you have provided such an insightful post, but I also don’t want you feeling pressure to have to write a near essay a week. 350-500 words will be perfectly sufficient and will also help you to hone your editing skills, to focus on precisely what is important and to state your case as clearly as possible.

Your reflections on the challenges of studying film history are impressive and you clearly demonstrate awareness of the importance of context, form, audiences and narrative. I like how you identify the origins of film language that is still in use today. Also drawing upon figures from the Deutsche Kinemathek helps to strengthen your argument.

A few minor points: although early cinema often featured middle-class families under threat from the working classes, the vast bulk of cinema audiences were actually working class. I know this seems counter intuitive, but then the majority of people were working class and cinema was an affordable pastime (think of the Nickelodeon for instance).

The static cameras of Fantomas certainly suggest that French films were focussed more on story than formal innovation, but it’s also worth considering the role that deep staging and blocking play in creating onscreen depth and complexity.

Excellent work overall, but less is more!