In part two of his blog, Shuks outlines key considerations for future users of the Guided Conversation tool.

This blog post builds on Guided Conversations Part 1. We outline key considerations for communities, organisations and individuals who may be interested in designing their own GC.

Although the topics that a GC aims to explore may be complex, such as wellbeing, three main principles can inform the design of a GC.

- GC participants are given an open platform to talk about what is important to them.

- Creative prompts are used as a starting point for conversation.

- The creative prompts need to be relevant to an overarching open question, places that are of interest for a GC and the people who will interact with the GC.

The first principle, above, is a key ethical consideration for the study of subjective topics, like wellbeing. The open platform mentioned by the principle is not only linked to the way participants are asked questions, but to their comfort. Comfort is provided by relationship building and ensuring that participants feel at ease with the individuals who are conducting GCs and in the spaces that GCs are held. Therefore, the individuals who will conduct GCs really matter, as do the places that will be used to hold GCs.

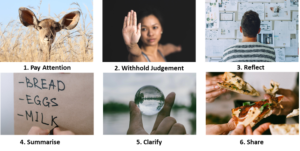

If appropriate, GCs can be co-ordinated as a way of thinking within a community, as opposed to a sit-down, one-to-one method. The points listed below outline what individuals in a community can think about during their natural, informal conversations. The scenario links to a community space where members of the community, volunteers and health and social care professionals can meet, e.g. a Community Hub.

- Start with an easy, open question that will encourage someone to talk about their opinion of the local area – e.g. how do you find living here / where you live?

- When a problem comes up, we can ask individuals to talk about how they might be supported with an issue.

- There is not always a solution, sometimes people just want to talk and that’s fine.

- If you know of any recommendations that may help the individual, e.g. a club, social activity and/or charity that can help, feel free to tell them about it.

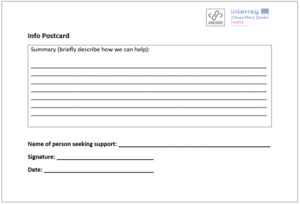

- For issues that require the involvement of a professional, you can fill in an Info Postcard and pass it on to a professional that deals with welfare issues. An explanation of an Info Postcard is provided in the paragraph below these points.

- An Info Postcard should only be filled in with the permission of the individual that it relates to and requires their approval, e.g. by signature.

- Respect the privacy of all individuals and do not pass on any details of your conversation to anyone else without their permission.

The approach outlined above can be appropriate for a drop-in help hub or social engagements that are organised for locals. In the case above, the Info Postcard refers to a simple piece of paper that can be given to a professional that is involved in the co-ordination of social and health care support. Example of an Info Postcard:

Interestingly, in the case above, there does not seem to be any creative conversational prompts – so, what happens with the GC’s second and third principles, which are all about creativity? Here, informal conversations are taking place between locals in their neighbourhoods and/or in a space that is part of a community. The surroundings become the conversation’s creative prompts and individuals can reflect on their neighbourhood’s influence by being there. An individual might think of a time when a certain building was their favourite grocers or memories of walking in the streets with friends. Like in HAIRE’s GC, the possibilities for sparking conversation are endless. Importantly, the prompts, i.e. being in the actual spaces, are still aligned with the GC’s overarching broad question: “how do you find living here?”

The example above does not intend to underplay the role of creativity in GCs. During group and/or one-to-one interactions, creative prompts can make the GC experience more engaging. Principles two and three, as listed in this blog’s opening paragraph, invite GC co-designers to think about what would be meaningful for their participants. In HAIRE, the spaces and cultural symbols in neighbourhoods and in people’s homes guided our co-design work. Hoiw However, in other cases, images that are more open to interpretation might be suitable. An example of this is the Talking Deck that was designed to talk about wellbeing in a support hub for individuals with experiences of homelessness. A blog about the Talking Deck can be seen here: Talking Deck Blog. In this case, the broad overarching starting point was to encourage individuals to talk about their day, or their week, form their own perspective.

Additionally, creative prompts do not necessarily have to be in graphic form. If interested in culture-led influences on wellbeing, it may be more appropriate to use physical objects that are well-recognised and valued by a certain culture. An interesting study, published in 2021, explored community-level opinions about Maori culture and belonging in New Zealand. Their toolkit used a selection of physical objects. The study authors reported the following:

“The aim of this [the physical objects] is to create a unique and shared experience, where the objects are used to assist participants in connecting with each other. Participants have an opportunity to comprehend and verbalise aspects of their and others’ identity and context. This experience aims to deepen their individual understanding of what belonging means to them and others.”

[Citation: Zino, I. et al. (2021) “things for thought – a creative toolkit to explore belonging,” Design for Health, 5(1), p.93. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/24735132.2021.1883822]

Written texts, stories and poems can spark memories, opinions and emotions in relation to a topic of interest. GC co-designers can use such resources as creative prompts too. In HAIRE, Kelly Stevens (University of Exeter) used a poetry workshop to explore the meaning of ageing and care with the project’s partners. A blog on this activity can be see here: Poetry, Caring and Ageing Blog. The session was structured around the following overarching question: “what does healthy ageing mean?” See below some of the poems and thoughts that were discussed at the workshop:

Therefore, when designing a GC, it is important to think about the creative skills that are present in the local community and/or the team that is co-ordinating the design of a GC. Creativity that is embedded in a community and amongst individuals who understand a GC’s topics of interest can be used to produce prompts that are relevant in particular settings. In fact, HAIRE’s work on the GC has highlighted the value of creativity when engaging communities with topics of interest that are loaded with meaning and, at times, influenced by uniqueness. The Social Innovation Group (SIG), University of Exeter, aims to build on its work in HAIRE and further develop understanding around the ways in which creativity can enhance inclusion and meanings around wellbeing.