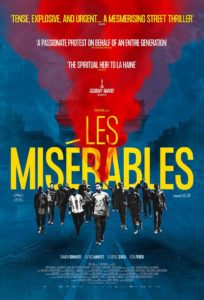

Ladj Ly’s Les Misérables

Les Misérables achieved global success and fame as soon as it was published. In exile on Guernsey Hugo would receive fan mail and begging letters from all around the world. The popularity of the work has never dimmed; indeed it has been one of the most filmed and adapted works of all time. The latest film entitled Les Misérables to come out of France is of particular significance, since it was directed by Ladj Ly, the Mali-born French film-maker, who comes from the banlieues in which he set his work. It is by no means an adaptation of Hugo’s book; rather, it is a response to it which, at first sight, has only a few, rather tenuous connections. The strongest of these is that Ly sets the film in Montfermeil, now one of the banlieues in Paris that is inhabited predominantly by those of African heritage, who are, for the most part, poor. We are in the same world as that depicted by Kassovitz in La Haine and, twenty five years after that exploded onto our screens, the tensions are as febrile as they ever were. In literary terms, however, Montfermeil evokes memories of Cosette’s ordeal at the hands of the Thénardiers, whose inn was located in Montfermeil, at that time a village not far from Paris. Then, as now, it was a place inhabited by les misérables; all that has changed is the demographic that represent the outsiders, the wretched within France. Ruiz, a policeman and one of the main characters in Ly’s film, observes laconically that not much has changed, whereupon his colleague observes that Cosette would now be called ‘Causefe’ and Gavroche ‘Gaveroche’.

Les Misérables achieved global success and fame as soon as it was published. In exile on Guernsey Hugo would receive fan mail and begging letters from all around the world. The popularity of the work has never dimmed; indeed it has been one of the most filmed and adapted works of all time. The latest film entitled Les Misérables to come out of France is of particular significance, since it was directed by Ladj Ly, the Mali-born French film-maker, who comes from the banlieues in which he set his work. It is by no means an adaptation of Hugo’s book; rather, it is a response to it which, at first sight, has only a few, rather tenuous connections. The strongest of these is that Ly sets the film in Montfermeil, now one of the banlieues in Paris that is inhabited predominantly by those of African heritage, who are, for the most part, poor. We are in the same world as that depicted by Kassovitz in La Haine and, twenty five years after that exploded onto our screens, the tensions are as febrile as they ever were. In literary terms, however, Montfermeil evokes memories of Cosette’s ordeal at the hands of the Thénardiers, whose inn was located in Montfermeil, at that time a village not far from Paris. Then, as now, it was a place inhabited by les misérables; all that has changed is the demographic that represent the outsiders, the wretched within France. Ruiz, a policeman and one of the main characters in Ly’s film, observes laconically that not much has changed, whereupon his colleague observes that Cosette would now be called ‘Causefe’ and Gavroche ‘Gaveroche’.

The film opens with a vision of the twenty-first century Parisian urchins triumphantly celebrating France’s victory in the 2018 World Cup. A young, black boy strides forth, swathed in a tricolore, and grinning triumphantly. Blink for a moment, and you could almost be looking at the exultant Gavroche standing boldly on the barricades, hailed with encouraging yells and whooping. (It is worth noting that the shooting of Gavroche foreshadows the way in which the twenty-first century police end up accidentally shooting a young black boy, Issa, in Ly’s film.) The opening scene welcomes these black children into the national celebrations – they experience fraternité, as they speak excitedly about the possibility of their heroes such as Mbappé scoring a goal. Football offers an arena where the young people in France’s black community can rejoice in the successes of their own. They happily join in the singing of la Marseillaise, the bloodthirsty brutality of which is highlighted through being sung at an event of national celebration and cheer.

As the black children return from the football match to their homes in the banlieues the happiness and the optimism immediately leaches from the film. They live in a world that is scarred by poverty and in a constant state of alert, poised for visits from and tensions with the police. The film focusses in particular on a trio of policemen who periodically visit the banlieues, both inflaming the tensions longterm, while cracking down hard on them as short-term measures. As a newcomer to the force the policeman Ruiz becomes part of a team that monitors tensions in Montfermeil, and works with Chris, a goading, mean-spirited bully and Gwada who tolerates the way in which Chris targets certain demographics. It is Chris who insists on stopping the car, so that he can go and harass a group of black teenage girls, who are simply waiting for a bus at the bus-stop. When one of them films the harassment as evidence, he smashes her mobile phone. Though he lacks the integrity and self-discipline of Javert, his role of difficult, antagonistic policeman echoes Javert’s capacity to pursue and to hound Jean Valjean. And the targetting of the teenage girls, whose only crime was the colour of their skin, reminds us that nineteenth-century France could be just as gratuitously unjust, as is evidenced at Champmathieu’s trial, when a court official observed that: ‘Je ne sais plus trop son nom. En voilà un qui vous a une mine de bandit. Rien que pour avoir cette figure-là, je l’enverrais aux galères.’ (206). (I can’t quite remember his name any more. But he looks like a brigand, that one. I’d send him to the galleys just for having that face.) Then, as now, the wrong appearance is enough to make individuals vulnerable to arrest. Furthermore, as Gwada and Chris introduce Ruiz to the area, they point out that one of the problems besetting the region is the number of Nigerian prostitutes, reminding us that ‘la déchéance de la femme par la faim’ (the fall of women through hunger) remains one of the evils of the twenty-first century, just as it had been identified by Hugo as one of the core failures of the nineteenth century also.

Les Misérables is a text that is obsessed with falling – there is the moral fall of Jean Valjean from grace, indicated by the title of an early section in the novel ‘La Chute’ (The Fall), which anticipates his literal fall from a ship into the sea; we see Fantine’s fall into prostitution, and Javert’s fall into the Seine, when he commits suicide. Hugo employs the imagery of precipices and vertigo throughout to evoke heart-stopping fear or the annihilating terror of absolute abandonment within the universe or, as in the case of Fantine, the corrosive anxiety of falling so far into poverty that it will prove impossible ever to climb back up and build a life to herself or for her child. ‘Vertige’ ‘escarpements’ ‘chute’ (Vertigo, steep slopes, fall) are words that recur time and time again, highlighting the fragile footing that les misérables have within the world. Ly cleverly mirrors the vertigo within Hugo’s work by situating chunks of the film up on the rooftops, and by following the loops and swoops of a drone, through which we can acquire a bird’s-eye view of the city. Such a vision looks back not only to Les Misérables, but also to Notre Dame de Paris and its famous evocation of Paris in the chapter entitled: ‘Paris à vol d’oiseau’ (A bird’s eye view of Paris). The arrival of the circus in Ly’s film offers an air of carnival that also recalls Notre Dame.

The echoes of Hugo’s works are fleeting yet pervasive. Apart from the fact that the school in Montfermeil is named after Victor Hugo, and Ruiz is thereby prompted to comment on the history of Montfermeil in Les Misérables, we have to wait until the end of the film for a direct reference. The film closes with a close-up of Hugo’s words: ‘Mes amis, retenez bien ceci. Il n’y a ni mauvaises herbes, ni mauvais hommes.Il n’y a que de mauvais cultivateurs.’ (My friends, take heed to what I am going to tell you. There is no such thing as a bad weed, or a bad man. There are simply bad cultivators.) But the overlaying with Hugolian imagery of a story set in the Parisian suburbs inhabited primarily by black people serves as a useful reminder of the fact that Hugo explicitly identifies within Les Misérables with a black man, when he names one of Enjolras’s allies ‘Homère: Hogu nègre.’ The sobriquet is important because it indicates Hugo’s epic ambitions – his epic is the culmination of a tradition extending from Homer to Hugo himself, but also because it enables Hugo to identify with a particular demographic, already vulnerable to exclusion and brutal treatment. Later in the book he indicates that the anguish of les misérables would be experienced amongst peoples and in lands far distant from the France that he evokes, when Thénardier announces that he is going to seek his fortune in America as a slave trader. By opening doors within his novel for such communities Hugo facilitated Ladj Ly’s response, a work depicting communities, technology and weapons that would have been utterly alien to him, even as the conflicts and tensions would have been all too chillingly familiar.

Recent Comments